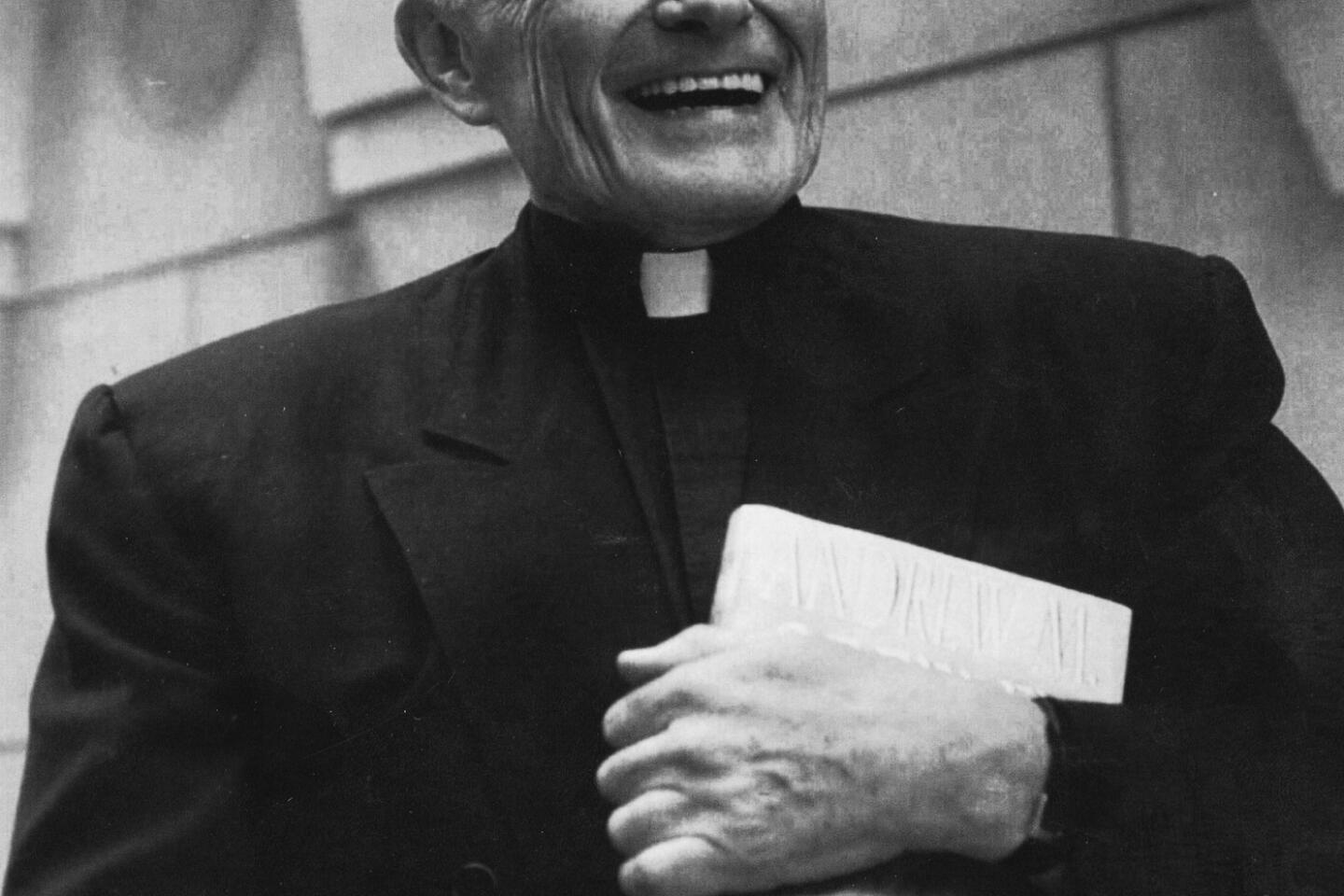

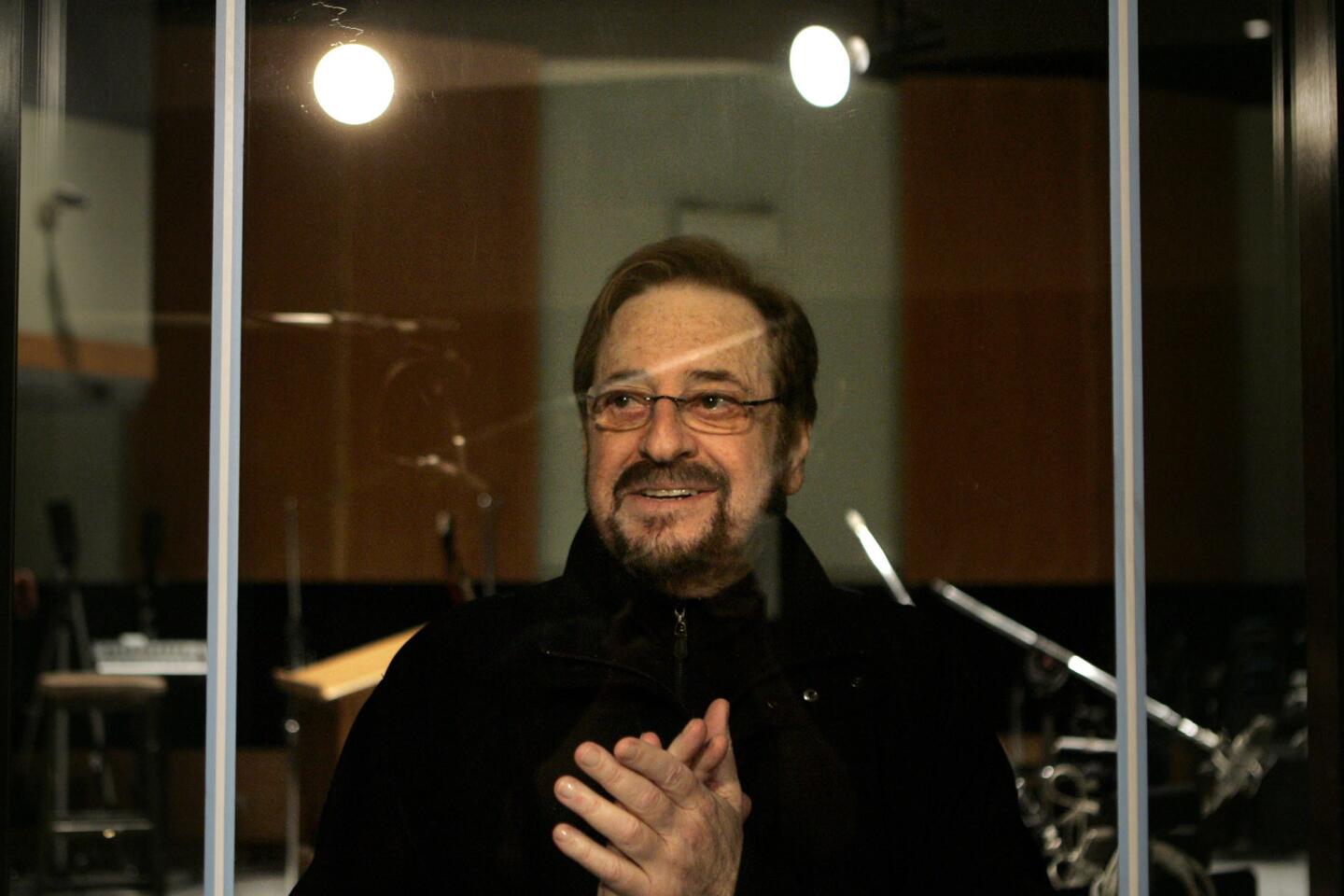

Dr. Dean Brooks dies at 96; key figure in filming ‘Cuckoo’s Nest’

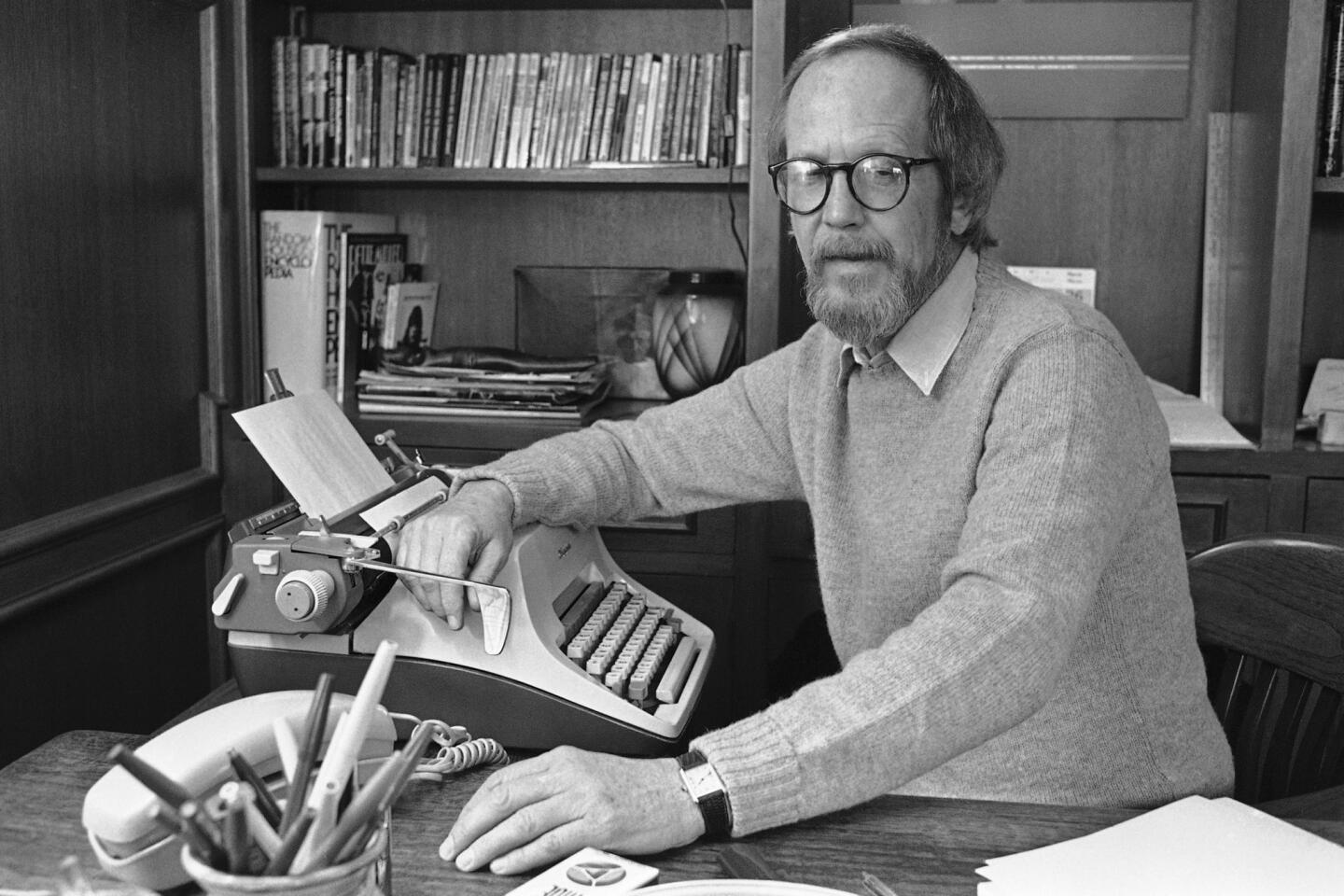

When he ran a large state mental hospital, Dr. Dean Brooks made some bold decisions, but one of the most daring was to heed the call of Hollywood.

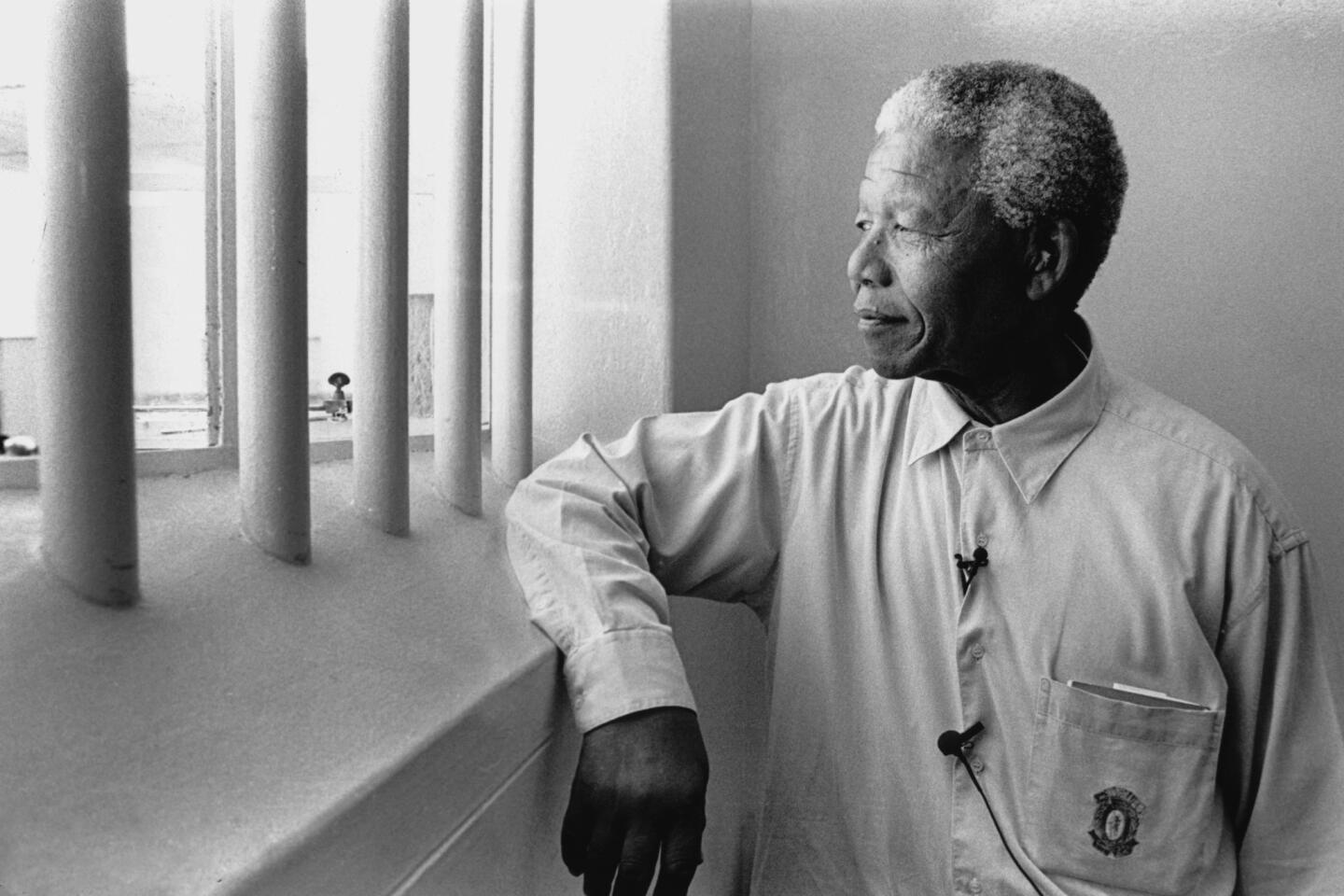

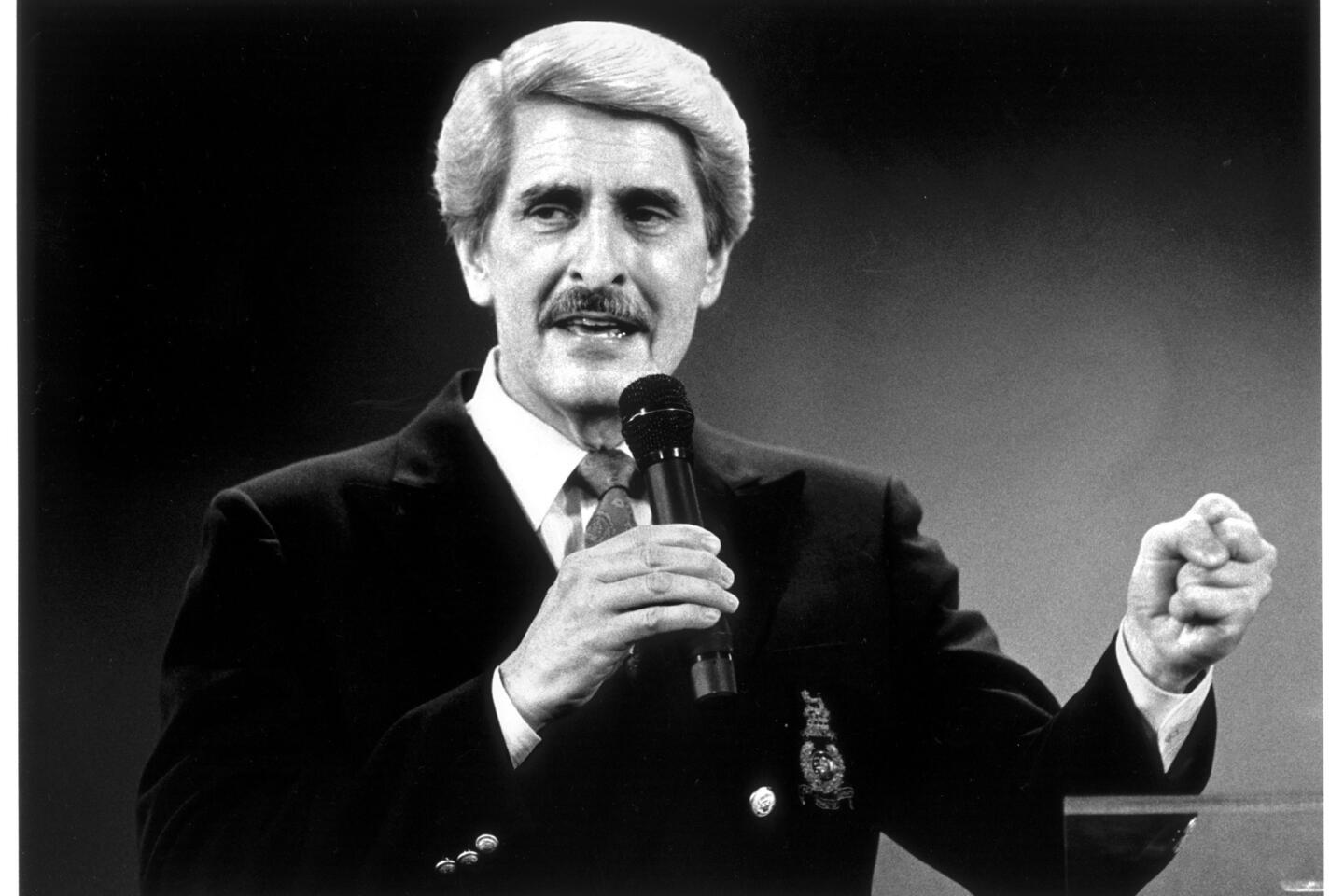

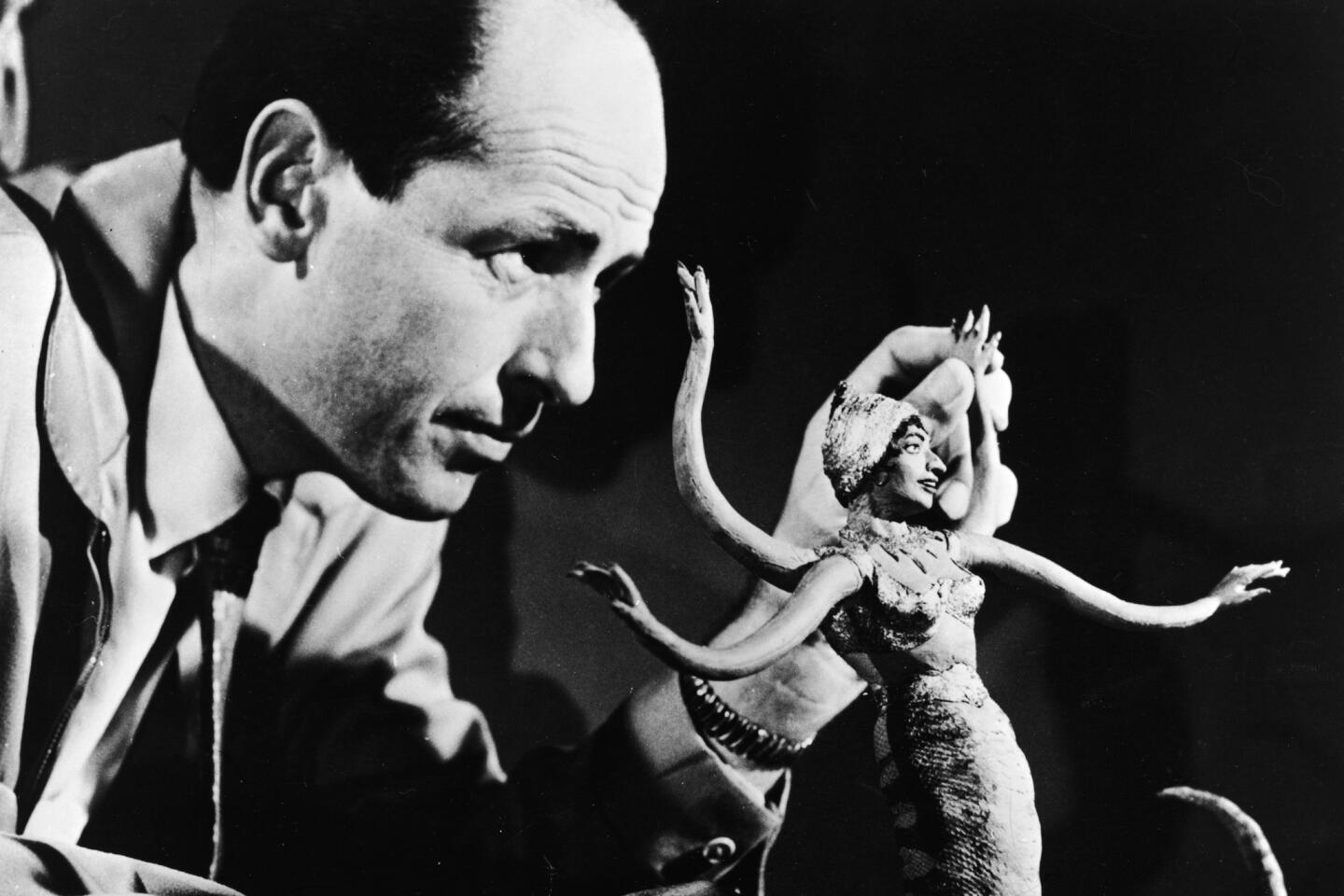

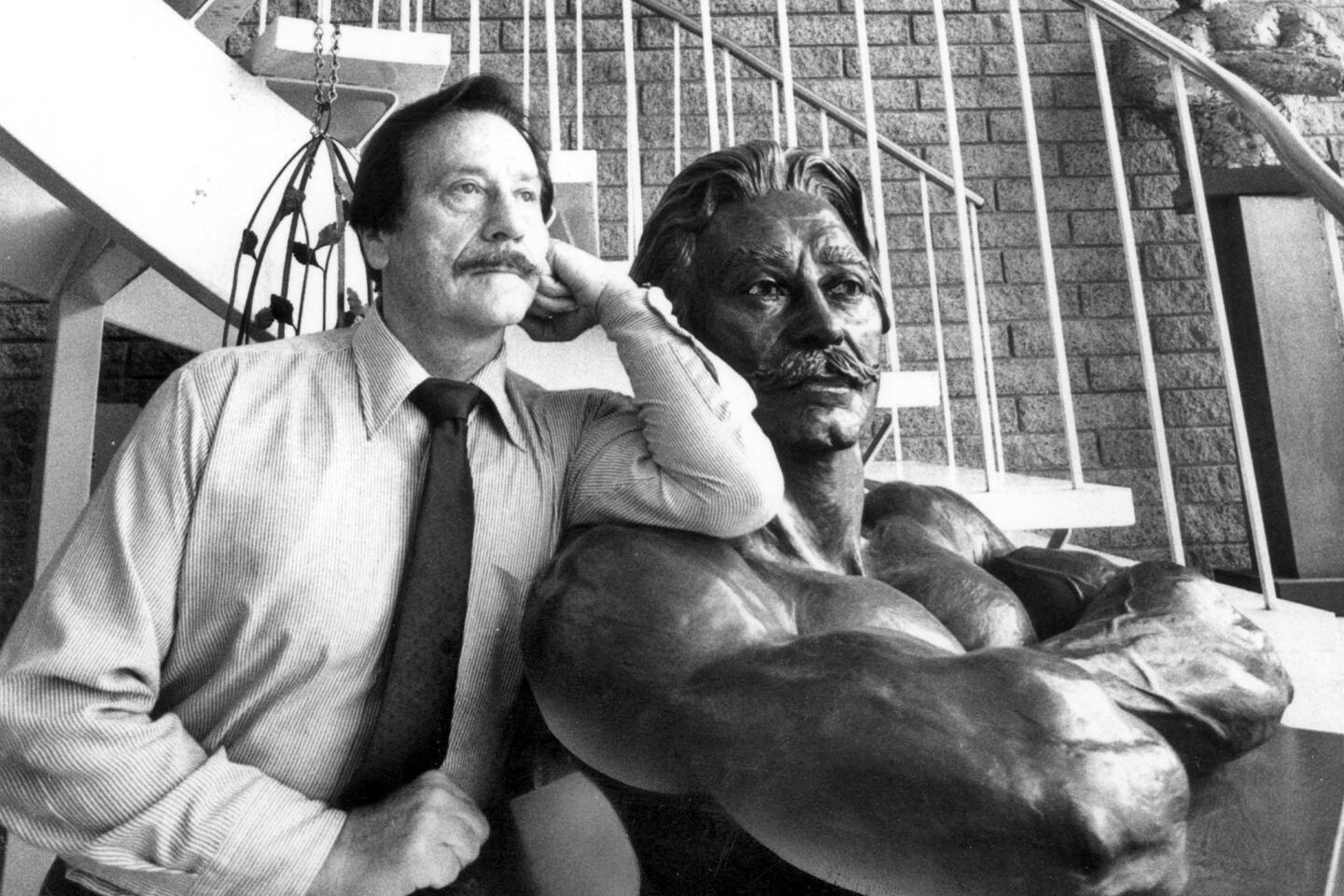

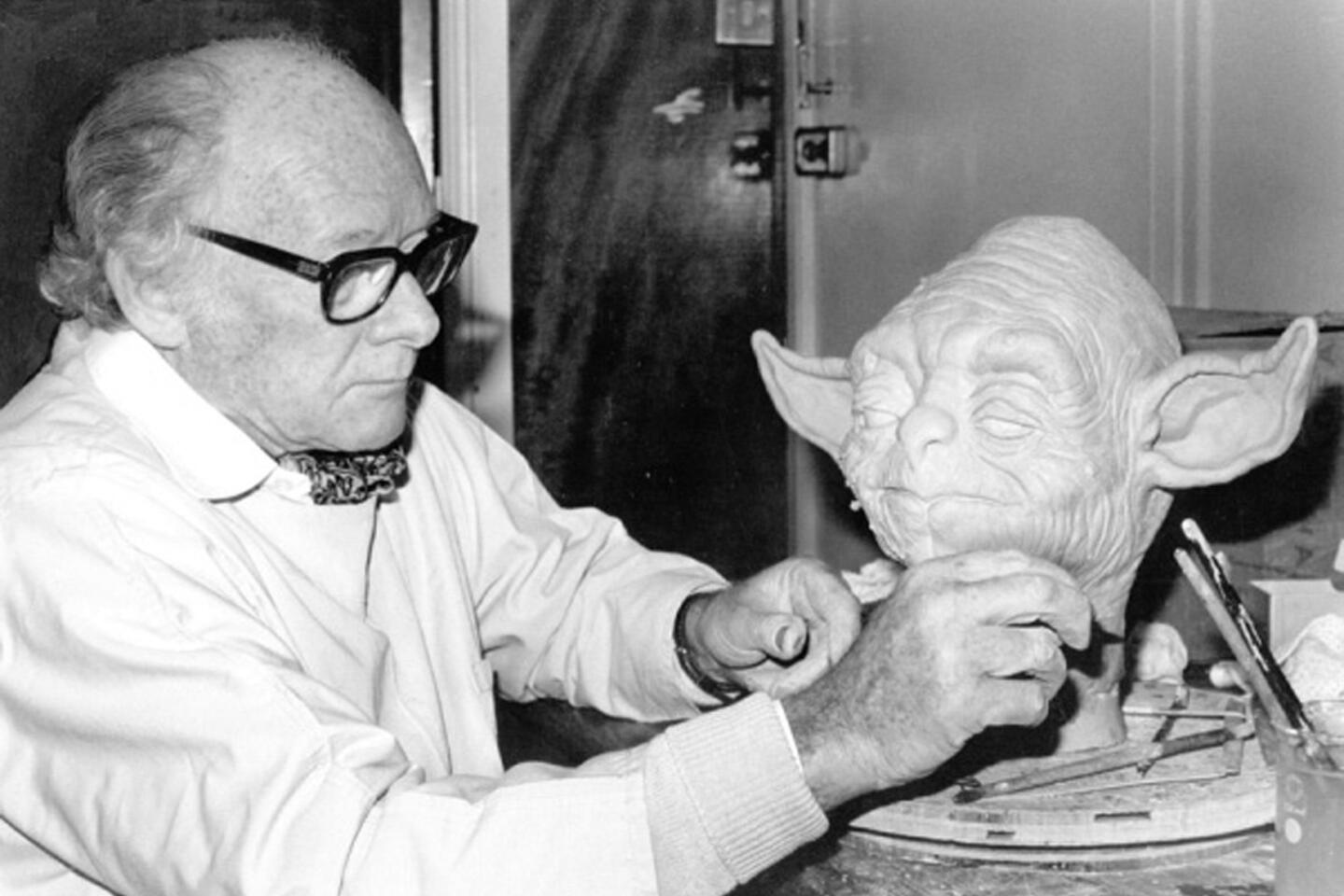

Over protests from his boss and many mental health professionals, Brooks allowed the cast and crew of “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest” into Oregon State Hospital for 14 weeks as they made the 1975 movie that became an Oscar-winning classic. Brooks believed so strongly in the film that he played a hospital psychiatrist, a go-along, get-along type who was tragically unwilling to rock the boat.

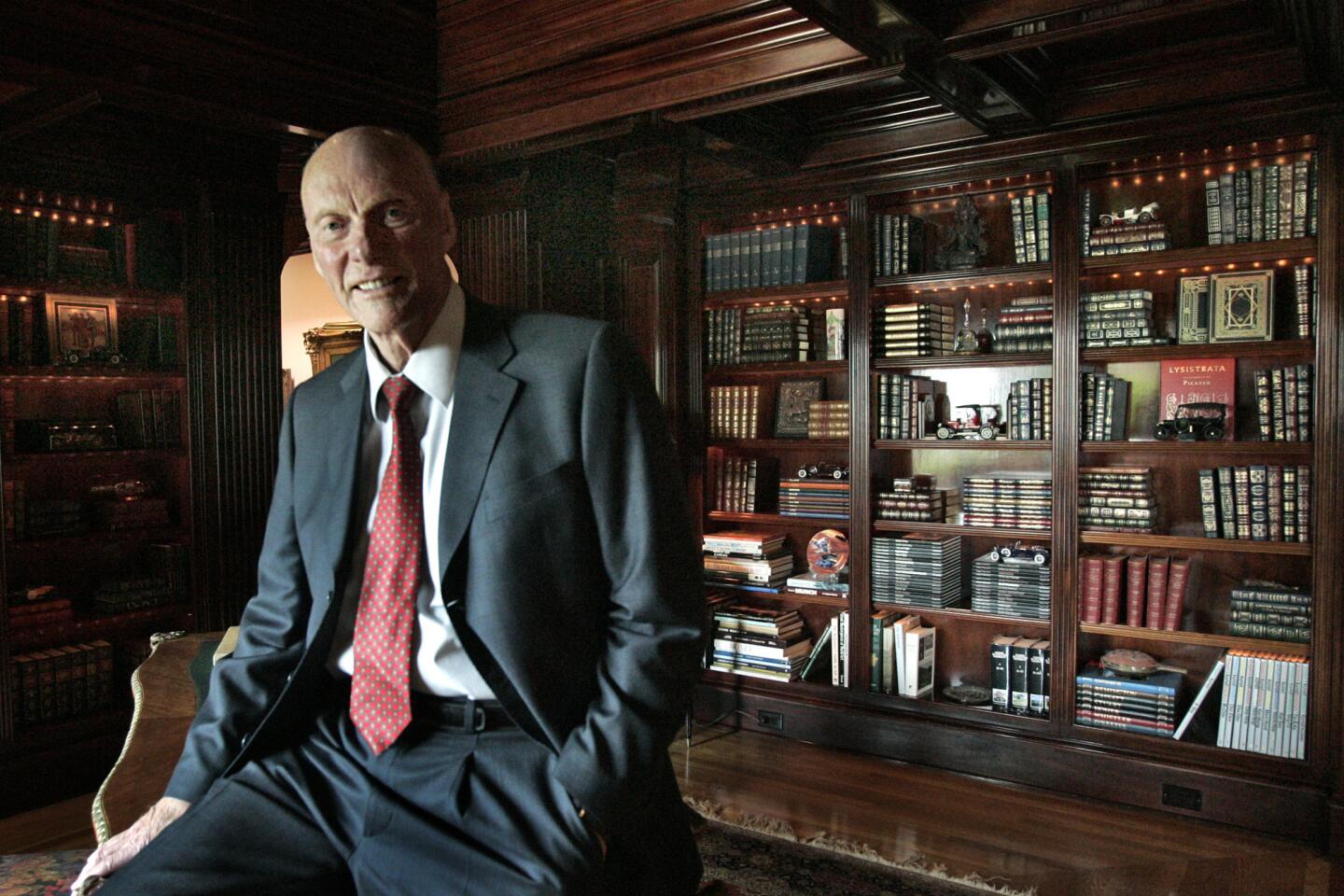

Brooks, who died May 30 in a retirement home in Salem, Ore., was in reality a progressive administrator. He was 96 and had been in failing health for some time, family members said.

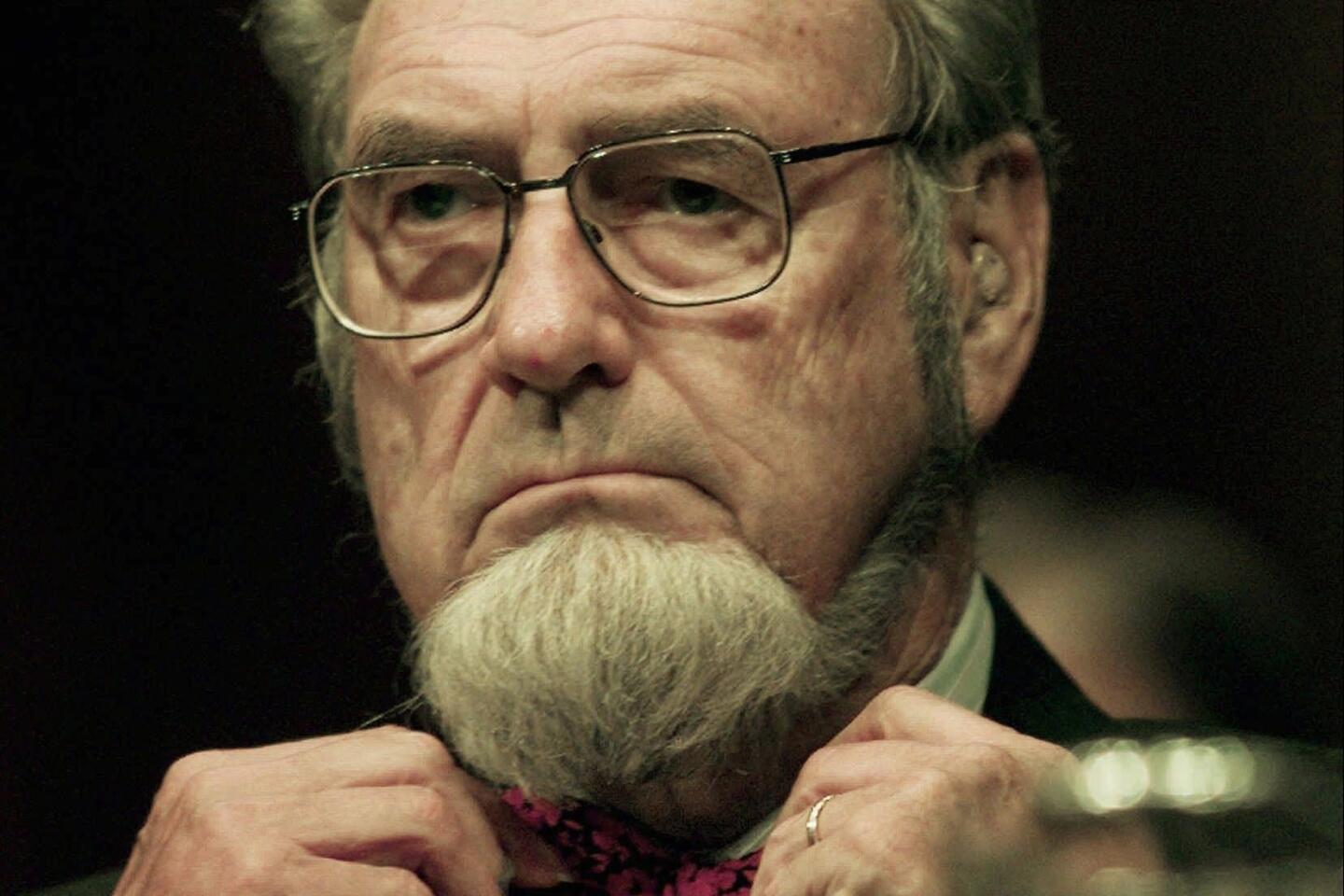

He remained actively engaged in mental health causes, and in recent years created an advocacy group promoting better treatment and facilities for mentally ill inmates wrongly confined to jails and prisons.

Brooks was the only hospital director willing to give unfettered access to Michael Douglas and Saul Zaentz, producers of “Cuckoo’s Nest,” he once told the Associated Press. Seeking a measure of realism for their adaptation of Ken Kesey’s 1962 novel, the filmmakers wanted their actors to sit in on therapy groups, witness such procedures as electroshock therapy and gain up-close knowledge of patients and caregivers before trying to portray them.

Brooks “thought it would be a wonderful opportunity for people to begin to discuss what was going on in mental health,” a daughter, Dennie Brooks, told the Los Angeles Times this week. “And he thought it would be fun.”

The patients wanted to do the film, but physicians were concerned about it “denigrating their profession,” she said. About 90 patients held jobs on the movie, mostly off-camera. Three doctors who initially opposed the idea wound up appearing in a staff meeting scene.

Auditioning before director Milos Forman for his role as chief psychiatrist, Brooks read from his script, threw down the pages in frustration, and, like many an actor before him, complained about his lines.

“I knew I’d flunked my test,” he told the Salem Statesman Journal in 2005. “But I said ‘Milos, you’ve got to make it real.’ ”

Brooks’ acting partner couldn’t have agreed more.

“Yeah, Milos,” Jack Nicholson told the director. “You’ve got to make it real.”

Ultimately, Brooks and Nicholson did it their way.

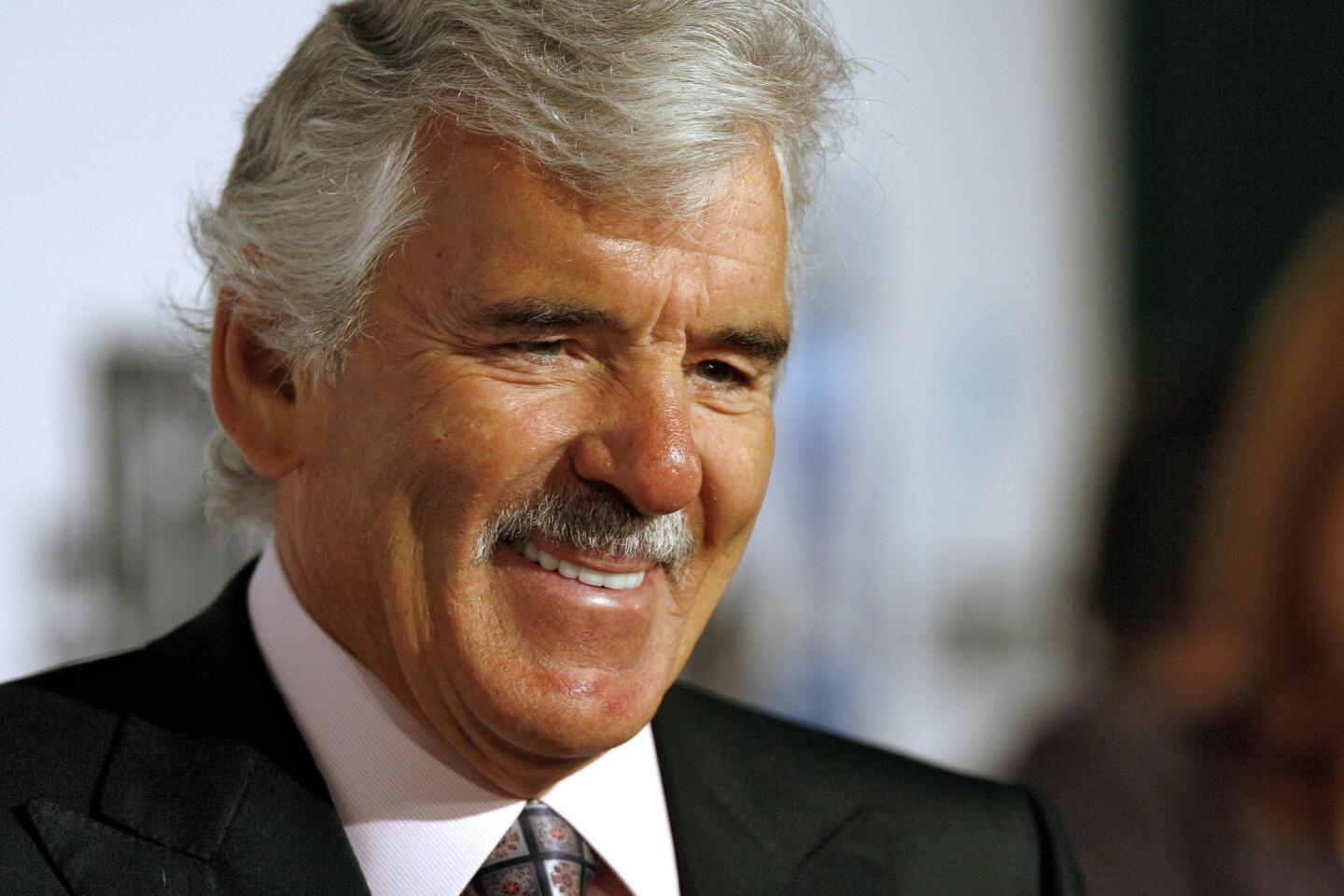

Convinced that Nicholson’s character is faking it, Brooks leans over his desk, lowers his voice, and asks: “Tell me, do you think there’s anything wrong with your mind, really?”

“Not a thing doc,” Nicholson responds with his syrupy smirk. “I’m a goddamn miracle of modern science.”

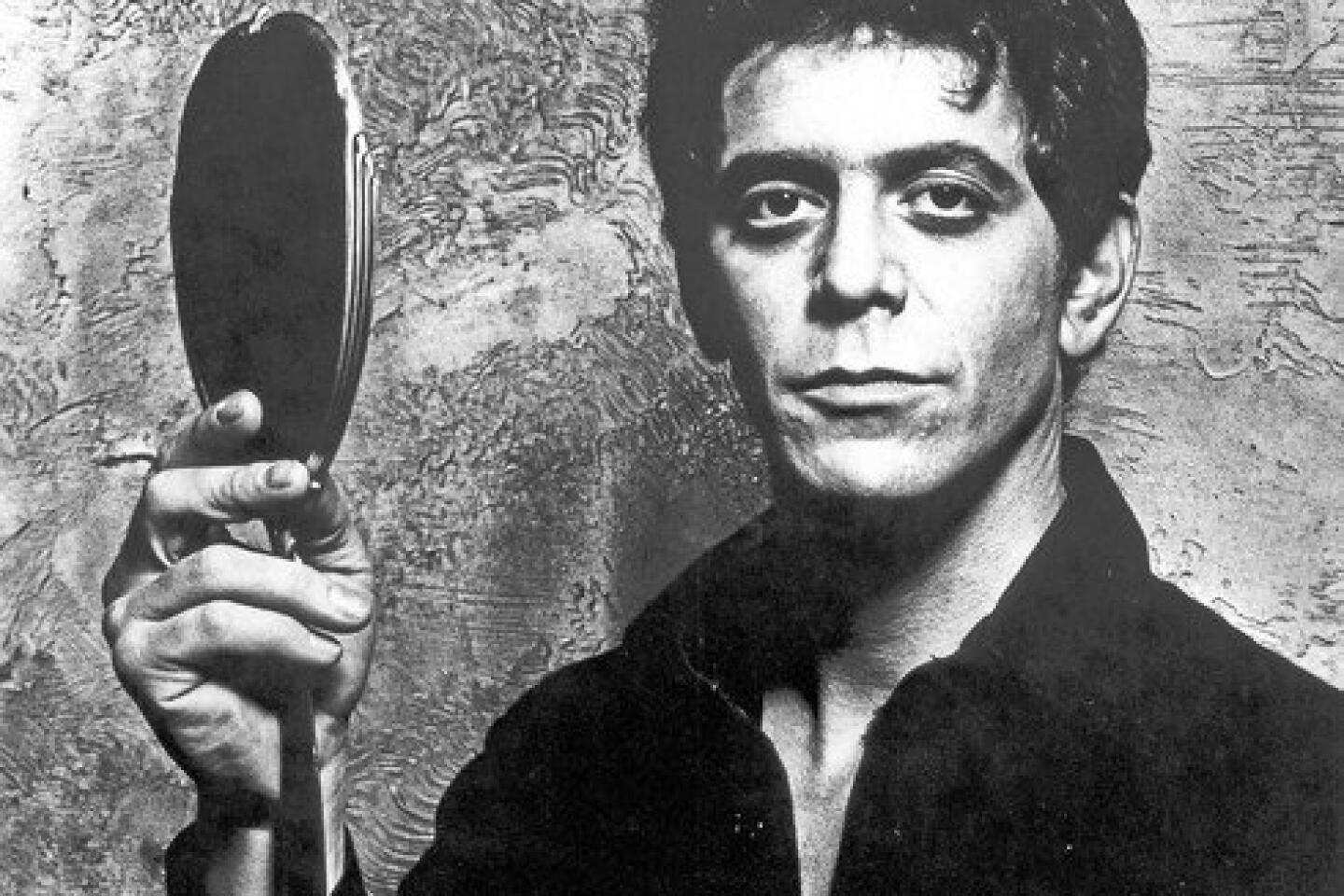

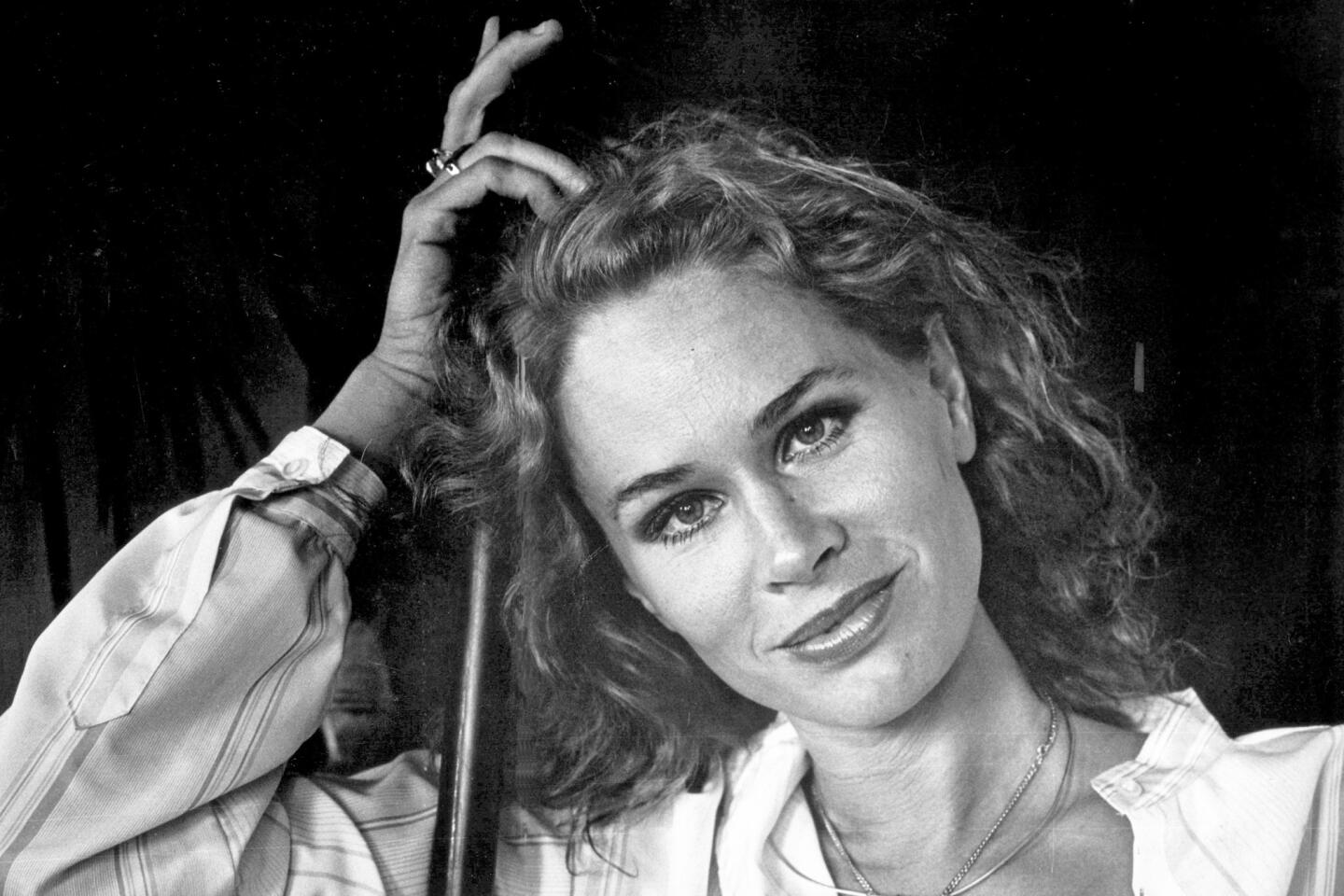

Their work captivated Louise Fletcher, the actress who received an Oscar for her portrayal of the hospital’s quietly chilling Nurse Ratched.

“This turned out to be one of the most brilliant improvised scenes I’ve ever witnessed,” she told The Times this week. “What was amazing was that Dean Brooks turned out to be such a good actor.”

Fletcher and Brooks struck up a lasting friendship and made sure to connect on their mutual birthday.

Born in Colony, Kan. on July 22, 1916, Dean Kent Brooks earned his undergraduate and medical degrees from the University of Kansas. Because he was known as “Deaner,” he is mistakenly listed in “Cuckoo Nest’s” credits as Dean R. Brooks.

During World War II, he served in the Navy, spending 26 months at sea.

He signed on at Oregon State Hospital in 1947. As its superintendent from 1955 to 1981, he ushered in changes that helped restore dignity to his patients’ everyday lives, colleagues said.

“He was at least 20 years ahead of his time,” said Greg Roberts, the hospital’s current superintendent. “Some of the things he did sound commonplace today but they were revolutionary for the time.”

Brooks let patients wear their own clothing instead of drab uniforms. He allowed overhead lights to be turned off at night so patients could sleep more easily. He put patients on committees that considered improvements in hospital procedures.

An avid hiker who once rappelled down a hospital wall, Brooks set up wilderness treks in which patients and staff helped one another negotiate steep rock faces.

“I’m not a patient any more,” one of his charges told him. “I’m a mountain climber.”

After retiring, Brooks grew increasingly frustrated with government’s failure to replace dramatically downsized hospitals with community care facilities. Passionate about “de-criminalizing” mental illness, he recruited more than a dozen mental health and judicial professionals for his advocacy effort. He named it the Dorothea Dix Think Tank, after the 19th century crusader for the mentally ill.

His wife, Ulista Jean Moser Brooks, died in 2006. In addition to Dennie Brooks, he is survived by two other daughters, Ulista Jean Brooks and India Brooks Civey; a brother, Robert; five grandchildren; and 10 great-grandchildren.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.