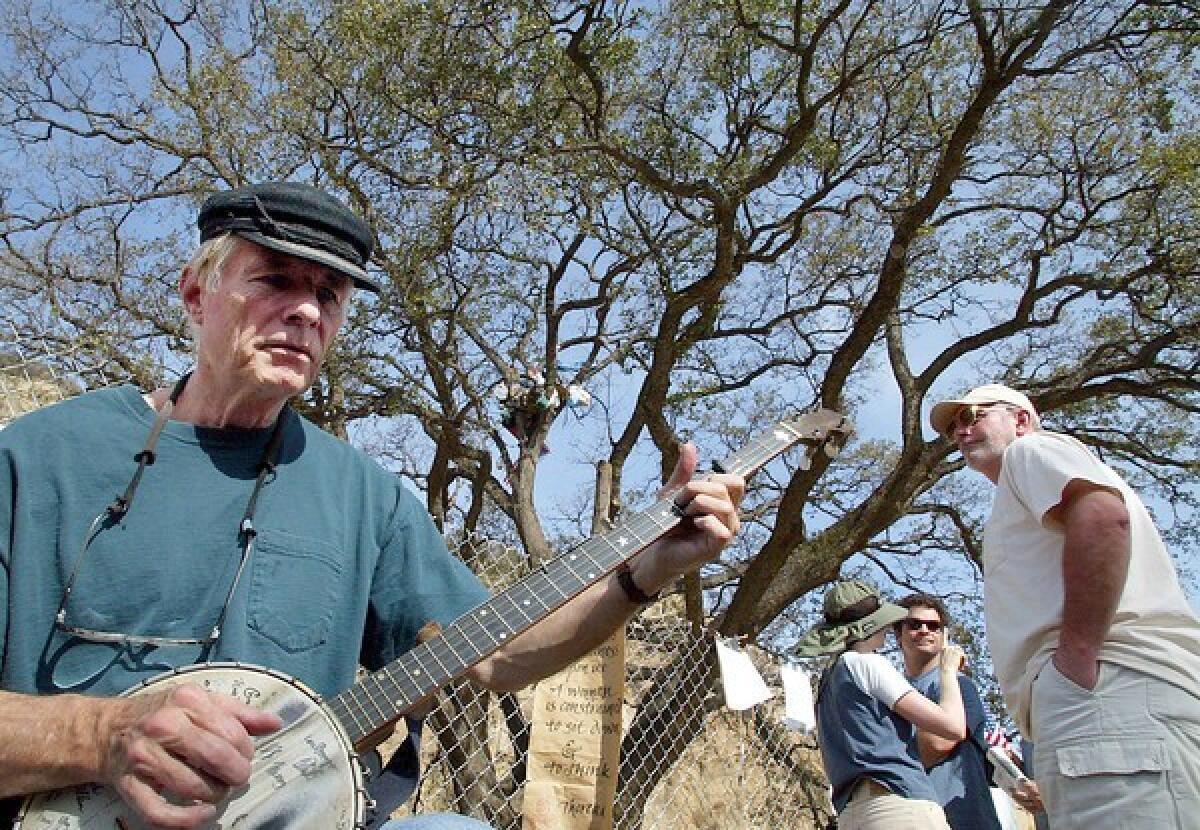

‘Banjo Fred’ Starner dies at 72; folk singer documented hobo music and culture

‘Banjo Fred” Starner, an economics professor and banjo-playing folk singer who documented hobo music and culture, has died. He was 72.

Starner, of Winnetka, died Oct. 25 at a West Hills rehabilitation facility of complications from pneumonia and the autoimmune disorder sarcoidosis, said his wife, Barbara.

“Fred Starner was very much a musician of the people, taking his cue from his mentor, Pete Seeger,” said Mary Katherine Aldin, a folk music historian. “A great percentage of his concerts were benefits for causes in which he believed.”

While studying at Oberlin College in Ohio in the 1950s, he became interested in American folk music after seeing Seeger perform, then taught himself to play the five-string banjo and 12-string guitar. Later, he would often perform at festivals with Seeger.

Starner was a professor at Drew University in New Jersey when he served as a singer and deckhand on the first crew of the sloop Clearwater, launched by Seeger in 1969 to travel New York’s Hudson River and spread the gospel of environmentalism. Starner’s wife joined him as first cook.

After moving to Los Angeles in 1987, Starner spent more time singing in coffeehouses than standing behind a lectern but still taught part time at community colleges.

The repertoire Starner brought to such venues as coffeehouses, rallies and schools included the usual sea chanteys, ballads and banjo tunes as well as original works on such topics as the Battle of Stalingrad, his grandmother’s bread -- and hobos.

American folk songs entertain but also “raise Cain,” which made him “comfortable with hobos, since they fan a radical spark here and there,” he wrote on his website.

Hobos are not bums, he was often quick to point out, but “people who rode the rails for a year or two to get their act together then went back to rejoin the rest of the world.”

He traced his interest in hobo culture to his childhood in Toledo, Ohio, where his mother gave hobos from the nearby rail yards “a bowl of soup and a peanut butter and jelly sandwich and 15 cents,” Starner told the Chicago Tribune in 2000.

As an adult, he rediscovered the hobo lifestyle when he sang “The Wabash Cannonball” at a Westside concert. The editor of the Hobo Times was in the audience and asked if he knew any more hobo songs.

Soon, Starter was regularly trekking to Northern California to visit the “hobo jungles” in Dunsmuir, once a thriving railroad town. As he regularly performed at National Hobo Assn. gatherings, he found that many younger hobos were unaware of their shared history of music, poetry and stories.

So he set out to preserve it in a documentary he co-produced and appears in called “That’s the Ticket Roadhog: The Hobo’s Song.” Completed several months ago, it is scheduled to be released online Dec. 1 at www.ciniweb.com.

The film weaves together footage of hobo music with stories of modern hobo culture. Front and center is the true story of Roadhog, an ailing hobo who robbed a bank so he could go to prison and receive medical care. In the film, a rapt and amused Seeger is shown listening as Starner sings the title track to him.

He was born George Frederick Starner on Aug. 6, 1937, in Toledo, to James and Charlotte Starner. His father was an engineer at a glass company, and his mother taught first grade.

After earning his bachelor’s degree in economics at Oberlin, Starner received a master’s from University of Michigan and a doctorate in 1970 from Ohio State University.

Political activism cost him his first teaching job, at Drew University, Starner later said. He joined the University of Wisconsin-La Crosse in 1974 and helped found a folk festival there that continues today.

After moving to Los Angeles so his daughter, then 16, could attend a dance academy, he proclaimed California “a great state for folk singers” because it had endless problems that he could sing about.

In his “Hobo’s Lullaby,” Starner summed up what was also one of his life philosophies:

A hobo is life at its core

Happiness is not making more

and more.

In addition to his wife, Barbara, whom he married in 1962, Starner is survived by his daughter, Natasha Starner Roper of Winnetka; and his siblings, Jacqueline Bartels of Toledo and James of Cincinnati.

A memorial will be held at 3 p.m. Saturday at the Unitarian Universalist Church of Studio City, 12355 Moorpark St., and will include a screening of “That’s the Ticket Roadhog.”

Instead of flowers, the family suggests donating to the Hudson River Sloop Clearwater, www.clearwater.org.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.