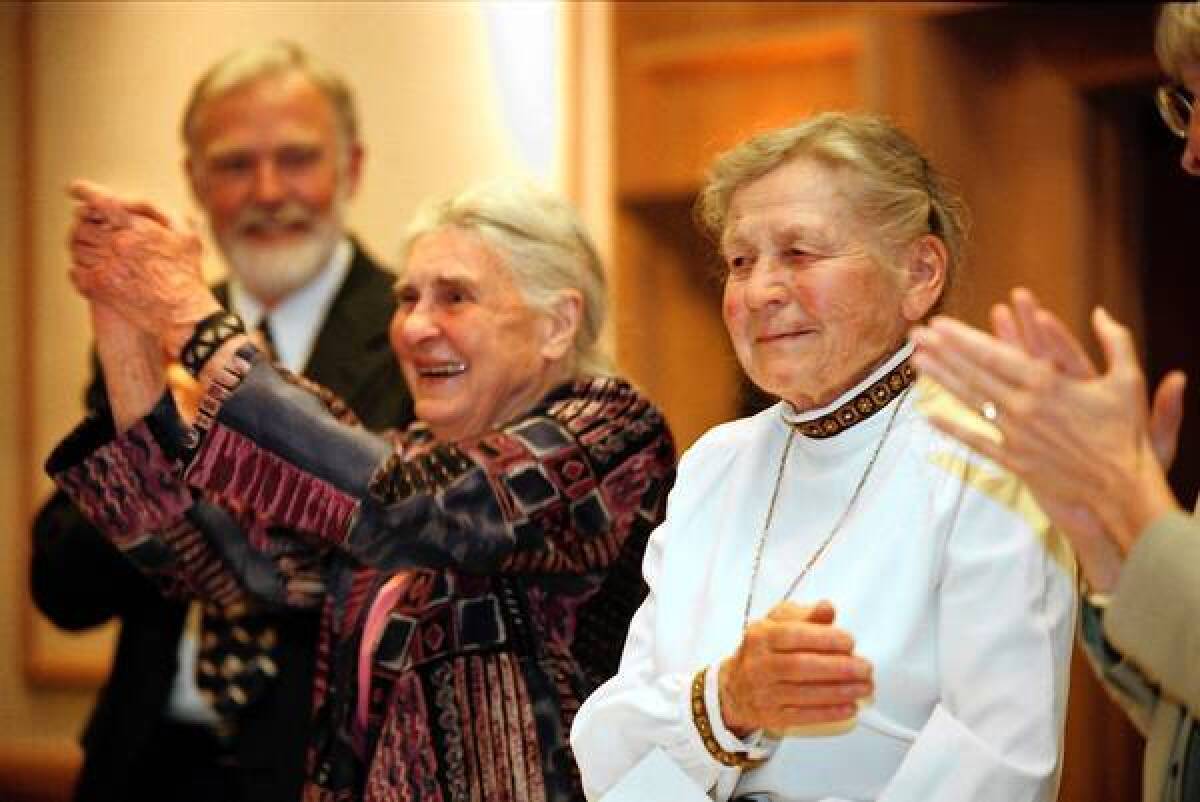

Ginny Wood dies at 95; pioneering Alaska environmentalist

Virginia “Ginny” Hill Wood led a life of adventure beginning at a young age, guiding horseback trips in her native Washington state, bicycling through Europe before and after World War II, serving as a WASP pilot and, after moving to Alaska, building a rustic backcountry lodge and leading wilderness treks.

But her lasting legacy may be her role as a pioneer Alaska environmentalist.

Wood died Friday of natural causes at her home in Fairbanks, Alaska, friends said. She was 95.

The outdoors enthusiast guided her last backcountry trip at age 70, cross-country skied into her mid-80s and gardened into her early 90s.

But she also “had a vision outside of her own personal interest. It was an interest for Alaska and the future,” said Roger Kaye, a wilderness specialist and pilot at the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge who worked at Wood’s Camp Denali wilderness lodge during the 1970s.

“She played a fundamental role in the beginning of the conservation movement in Alaska,” Kaye said. “The Alaska Conservation Society was founded in her living room in the late 1950s.”

Another of Wood’s friends, Karen Brewster, recently edited and published “Boots, Bikes and Bombers: Adventures of Alaska Conservationist Ginny Hill Wood.”

“She was a very inspiring woman and did many things that were unusual for women of her time that women today take for granted,” Brewster said.

She was born Virginia Hill on Oct. 24, 1917, and grew up in Washington and Oregon, where she came to appreciate the outdoors. Always called Ginny, she rode horses, skied, hiked and went river rafting. She took her first plane ride at age 4, sitting in her father’s lap as they flew with a barnstorming pilot.

In 1938 she dropped out of Washington State University to bicycle through Europe for a year before resuming her studies at the University of Washington. Eager to learn to fly, she joined the Civilian Pilot Training Service and then the Women Airforce Service Pilots corps.

During World War II she ferried military planes from Long Beach to wherever they were needed around the country. After the war ended, she found odd jobs as a pilot, transporting cargo, flying war-surplus planes to Alaska and leading airborne tourist jaunts.

In the late ‘40s she and a fellow WASP pilot, Celia Hunter, took a bicycling tour of postwar Europe.

“All the youth of Europe had spent years either fighting, being interred or being stuck in a town where you had to sleep in a bomb shelter every night,” Wood told The Times in 2001. “So the war was over, and the youth of Europe was on the road. Going there at that time changed our lives.... It made us citizens of the world.”

Back home, the two friends returned to Alaska and decided to settle in Fairbanks. In 1950, Ginny married Morton “Woody” Wood. He worked as a forest ranger at Mt. McKinley National Park, which had been administered by the National Park Service long before Alaska became a state in 1959.

The Woods and Hunter pooled their resources to buy land in the Alaska wilderness under the Homestead Act and in 1952 built Camp Denali as a tourist outpost and base for backcountry exploration. The accommodations were spartan but attracted visitors drawn to the area’s natural beauty.

Wood’s marriage lasted only a few years, but she and Hunter continued to operate the remote tourist resort and became known for their conservation efforts. They co-founded the Alaska Conservation Society, the state’s first organization to guard its natural resources, and lobbied President Eisenhower to designate the Arctic National Wildlife Range in 1960.

Wood joined with other environmental activists opposing a plan to use nuclear explosives to build a deep-water harbor in northwest Alaska and other proposals to dam the Yukon River and mine the Fortymile River.

“Ginny’s philosophy and approach to life was cherishing nature and friends, fighting for what you believe in, living a simple life and not leaving a big footprint,” Brewster said. “She loved the outdoors and the wilderness, and it was really important to her to have those places protected.”

Wood is survived by a daughter, Romany Wood, of San Cristobal, N.M.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.