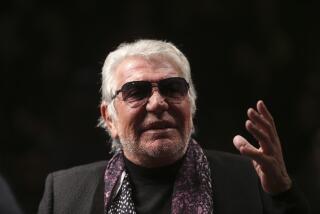

Giulio Andreotti dies at 94; seven-time Italian prime minister

Giulio Andreotti, the seven-time Italian prime minister who dominated Italian politics after World War II, but was tainted by accusations of Mafia ties, died in Rome on Monday after suffering from respiratory problems. He was 94.

A lawmaker who lived through Italy’s monarchy and its fascist era and sat in every Italian parliament since 1945, Andreotti had a career so intertwined with the country’s 20th century history that when he faced trial for seeking favors from Cosa Nostra, the entire system was on trial too.

“Andreotti was politics,” Pier Ferdinando Casini, head of the Italian centrist Democratic Center Union party, said Monday. “He condensed good and evil. An extraordinary personality.”

PHOTOS: Notable deaths of 2013

Born to schoolteachers in Rome in 1919, Andreotti obtained a law degree at Rome University before working during World War II as a librarian at the Vatican, where he put his networking skills to good use. He met future Christian Democratic Party leader Alcide De Gasperi, who took him under his wing, making him his secretary and a member of Italy’s national assembly, which drew up the nation’s constitution.

After becoming a junior government minister at age 28 in 1947, Andreotti first reorganized the country’s cinema industry, drafting legislation that helped it become the second largest in the world after the U.S. by the 1950s.

By then, Andreotti was skillfully navigating the Byzantine world of Italian politics. He became prime minister for the first time in 1972 and served for the last time between 1989 and 1992, by which time he had been appointed a senator for life.

Nicknamed “The Hunchback” because of his stooped appearance and “Beelzebub” by his detractors for his backroom politicking, Andreotti famously denied the idea that power wears one out, asserting instead that “power wears out those who don’t have it.”

A talented deal maker with an ironic sense of humor, Andreotti worked to defend Italy’s Christian Democrats as the Communist Party gained votes, before forming a minority Christian Democratic government in 1978 with external backing from the Communists. The ploy proved to be typical of Andreotti’s political cunning, giving the Communists a taste of power but not true power sharing, while weakening the party as many Communist supporters were put off by their decision to make deals.

As prime minister in 1978, Andreotti refused to negotiate with the leftist Red Brigades guerrillas, who kidnapped former prime minister and Christian Democratic Party leader Aldo Moro. After 55 days in captivity, Moro was found dead of gunshot wounds.

Andreotti later turned his attention to foreign affairs, cultivating ties with Arab governments as foreign minister from 1983 to 1989 while keeping close contact with the U.S., which had long looked upon the Christian Democrats as a vital bulwark against the Communist threat.

An ardent Catholic, Andreotti also enjoyed close ties to the Vatican and was nicknamed “the permanent secretary of state of the Vatican” by former Italian President Francesco Cossiga.

After the Christian Democratic Party collapsed in the early 1990s amid a torrent of corruption scandals, Andreotti’s fortunes waned when he was accused by a Mafia turncoat of meeting and exchanging kisses of respect with Salvatore “Toto” Riina, the head of Sicily’s organized-crime network. The Christian Democrats were suspected of cultivating ties with the mob to win key votes in Sicily and pouring money into building projects that made Mafia-backed firms millions.

Andreotti denied mob links and staunchly defended Salvatore Lima, the former mayor of Palermo and his main aide on the island, who was killed in 1992 amid allegations he had been Andreotti’s ambassador to the mob and was murdered when he failed to come up with political payoffs.

Andreotti was also put on trial on charges that he ordered the murder of journalist Mino Pecorelli, who was reportedly set to publish details of Andreotti’s alleged Mafia links.

Andreotti was convicted, but the verdict was overturned on appeal. Charges of Mafia ties after 1980 were also thrown out, although in 2004, a court ruled that he had maintained links with mob bosses up until 1980, but the statute of limitations on such charges had run out.

“Apart from the Punic Wars, for which I was too young, I have been blamed for everything,” Andreotti said.

In 2008, a film made about Andreotti’s life, “Il Divo,” won the Jury Prize at the Cannes Film Festival. Andreotti reportedly walked out on the film, which tackled the murkier allegations made against him.

Andreotti is survived by his wife, Livia Danese, four children and grandchildren.

Kington is a special correspondent.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.