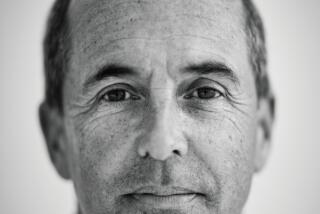

James D. Houston dies at 75; novelist, essayist whose works explored California

James D. Houston, a novelist, essayist and short-story writer firmly rooted in the West, whose works explored his native California, Hawaiian culture and, in collaboration with his wife, the World War II internment of Japanese Americans, died Thursday at his home in Santa Cruz. He was 75.

His death was due to complications of cancer, according to his daughter Gabrielle.

Houston was the author of nine novels, including “Snow Mountain Passage” (2001), inspired by a personal link to the ill-fated Donner Party of early California history, and “Bird of Another Heaven” (2007), about a 19th century woman of Hawaiian and California Indian ancestry.

“Whether in fiction or nonfiction, few writers have more consistently addressed the enduring issues arising out of the California experience than James D. Houston,” said California historian and USC professor Kevin Starr. “For those of us writing about the Golden State, he set standards by which the rest of us judged our own efforts.”

With his wife, Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston, he also helped conceive and co-wrote “Farewell to Manzanar” (1973), a classic first-person account of her family’s experiences during and after their detention at the Manzanar camp. With more than 1.5 million copies in print, it is a staple of high school and college reading lists and was made into an Emmy-nominated television movie in 1976.

Wakatsuki Houston initially planned to write the story for her family as a document of a confusing and sorrowful period in their lives, but her husband convinced her that it deserved a broader audience.

“He said, ‘That’s not just a story for your family but a story that every American should read,’ ” she said Friday.

He lived with his wife in an old Victorian house in Santa Cruz that, they learned after many years of residence, had been the last home of Patty Reed, the daughter of James Reed, one of the leaders of the Donner Party.

Houston had been researching an influential men’s club in San Jose in the late 1980s when he went to interview the club’s eldest member, an octogenarian named Frazier Reed II. In Reed’s home he spotted a picture of an old house that seemed very familiar. “My God, Frazier, that’s my house!” he exclaimed, to which Frazier replied, “Maybe it’s your house now, but it should have been my house.”

Reed spent the next several hours recounting his disinheritance and the ordeal in the Sierra Nevada that involved his great-grandfather some 150 years earlier. When Houston learned that Patty Reed spent the last 10 years of her life in his house and died in his bedroom in 1923 at age 85, he experienced what he often referred to as the “literary buzz . . . a little signal from the top of my head that there is some mystery here, or some unrevealed linkage that will have to be explored.”

Several years passed before Houston finally plunged into research, retracing the Donner Party’s trail and locating letters, diaries and other narratives by and about the Reeds and the horrifying events in the winter of 1846-47, when some members of the expedition resorted to cannibalism to survive. He wrote “Snow Mountain Passage” as a dual narrative, alternating between James Reed’s adventures and an elderly Patty Reed’s recollections of the journey that unfolded when she was a young girl.

The book was well-received by critics, such as novelist Carolyn See, who wrote in the Washington Post: “The novel takes one of the most ghoulish, garish parts of our national myth and transforms it into a dignified, powerful narrative of our shared American destiny.”

Houston’s next novel also used history as a launching point. An oral history led him to the story of Nani Keala, the daughter of a Pacific Rim emigrant who went up the Sacramento River with John Sutter in 1839 and helped build the fort that bears Sutter’s name. The book explores California’s beginnings and the famous and obscure characters whose machinations and dreams molded the state.

“Jim epitomizes what we think of as a California writer,” Alan Soldofsky, head of the creative writing program at San Jose State, where Houston was writer-in-residence three years ago, said Friday. “He had a consummate awareness of place and of the effect of both the natural and human communities on the writer’s psyche living on the edge of the continent.”

With UC Davis professor W. Jack Hicks, novelist Maxine Hong Kingston and poet Al Young, Houston produced “The Literature of California” (2000), an anthology encompassing three centuries of literary history, from early Chumash legends to Mark Twain and Carlos Bulosan.

The son of poor parents from West Texas, Houston was born in San Francisco on Nov. 10, 1933. He attended the city’s high-achieving Lowell High School, whose polyglot student body opened his eyes to a different America from the one his parents knew. In 1952, he entered San Jose State, where he met the fellow journalism student who became his wife. They married in 1957.

In addition to his wife and daughter, both of Santa Cruz, he leaves a son, Joshua, of Hawaii, and another daughter, Corinne, of Santa Cruz.

Houston earned a bachelor’s degree from San Jose State in 1956 and a master’s in American literature from Stanford, where he studied with Wallace Stegner, in 1962.

He and his wife had been married 15 years before she finally opened up about her experiences at Manzanar, one of the 10 internment camps where thousands of Americans of Japanese descent were held during World War II. No one in her family spoke of those years until one of her nephews, a product of the civil rights movements of 1960s and ‘70s, asked her “what it felt like to be in prison.” She broke into hysterical tears.

When she calmed down, she promised to write something for the family about Manzanar. When she told her husband about her “project,” he was stunned to learn of the burden she had been carrying for decades. Dozens of books had been written about the camps but few from the perspective of someone who had endured one. He convinced her that she had to share the story with the world.

“He was my shrink. He helped me get it out,” Wakatsuki Houston recalled Friday. “He’d write a draft, I’d write a draft. It was a true collaboration.”

Houston was known as a gifted teacher of writing. His family asks that in lieu of flowers, donations go to the Squaw Valley Community of Writers, P.O. Box 1416, Nevada City, CA 95959.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.