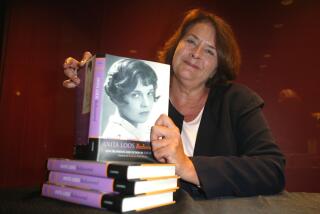

Marilyn French dies at 79; author of feminist classic ‘The Women’s Room’

Marilyn French, a writer and feminist scholar whose provocative 1977 novel “The Women’s Room” captured the frustration and fury of a generation of women fed up with society’s traditional conceptions of their roles, died Saturday at a hospital in New York City. She was 79.

The cause was heart failure, said Gloria Jacobs, executive director of the Feminist Press, which published her last major work, the four-volume “From Eve to Dawn: A History of Women,” in 2008.

Although it received mixed reviews, “The Women’s Room” became a feminist classic, selling more than 20 million copies in two dozen languages with a story that spoke powerfully to women seeking liberation from societal norms in the latter quarter of the 20th century. It traced the evolution of Mira, a repressed suburban housewife in the 1950s who divorces her brutish husband in the 1960s, goes to Harvard and finds friendship with other women seeking to redefine their lives in the midst of sweeping social change.

“It came at the right moment,” said Feminist Press founder Florence Howe, who knew French for 30 years. “It said to women you just have to stop being oppressed, you have to stand up and fight for yourself. Women heard that. Women recognized themselves.”

The novel’s most-quoted line -- “All men are rapists, and that’s all they are,” spoken by the protagonist after the near-rape of her daughter -- was often erroneously attributed to French herself, giving critics what they thought was proof of the author’s man-hating rage. The accusation infuriated French. “What I am opposed to,” she told the London Times a few years ago, “is the notion that men are superior to me.”

Although she said the novel was not autobiographical, her protagonist’s trajectory mirrored her own. There was, she said, “nothing in [it] I’ve not felt.”

She was born in New York City on Nov. 21, 1929. Her father, Charles Edwards, was an engineer who “didn’t really exist as a presence in my life,” she once told an interviewer.

Her mother, Isabel, was the dominant force, who refused to let her husband beat Marilyn and her younger sister.

“From this,” French told Britain’s Guardian newspaper in 2006, “we were taught never to bow to authority.”

She put herself through Hofstra College (now Hofstra University) in New York, graduating with a bachelor’s degree in English literature a year after marrying Robert French in 1950. He wanted to be a writer, so she worked a series of “paralyzing” office jobs to support him; he later became a lawyer.

Their marriage was unhappy and ended in 1967, making her one of the first in her circle of friends to experience divorce. “My mother was appalled. As far as she was concerned, if my husband didn’t beat me or gamble or drink, then I should stay,” she told the London Times in 2007. Her marriage, she added, “was absolutely horrible and I have never gotten over it.”

When her marriage finally collapsed, French was a mother of two and teaching at Hofstra, where she had earned a masters in 1964. She went to Harvard on a fellowship and in 1972 earned a doctorate in literature with a thesis on James Joyce’s “Ulysses.” For the next four years she taught English at the College of the Holy Cross in Worcester, Mass.

During this period, two events helped radicalize her: reading Kate Millett’s feminist treatise “Sexual Politics” and the rape of her then-18-year-old daughter, Jamie, in 1971.

French championed the prosecution of the rapist, even though the district attorney tried to talk her into dropping the case. The rapist confessed after her daughter testified at the trial. He was convicted and sent to prison.

Noting once that contempt for women was “not an accident,” she began to develop her first novel. Her goal, she told the New York Times years later, was “to tell the story of what it is like to be a woman in our country in the middle of the 20th century.”

“The Women’s Room” earned mixed reviews from critics. Her bleak view of the relationship between the sexes “is powerfully stated,” Brigitte Weeks wrote in the Washington Post, “but still invokes a lonely chaos repellent to most readers.” Libby Purves in the London Times said French had created male characters who were “malevolent stick figures, at best appallingly dull and at worst monsters.”

In the New York Times, Christopher Lehmann-Haupt wrote: “The best compliment I can pay it is that I kept forgetting that it was fiction. It seized me by my preconceptions and I kept struggling and arguing with its premises. Men can’t be that bad, I kept wanting to shout at the narrator. There must be room for accommodation between the sexes that you’ve somehow overlooked. And the damnable thing is, she’s right.”

French went on to write five more novels, including “The Bleeding Heart” (1980), “Her Mother’s Daughter” (1987), “Our Father” (1994) and “In the Name of Friendship” (2006). Her nonfiction includes “Beyond Power: On Women, Men and Morals” (1985) and “The War Against Women” (1992).

Several of her books, including the massive history “From Eve to Dawn,” were written after her diagnosis of esophageal cancer in 1992. French, a longtime smoker, underwent two debilitating years of treatment, including radiation and chemotherapy, that broke her body, weakening nearly every organ as well as her bones. She defied the grim prognosis and emerged cancer-free.

Before her death, she completed another novel, “The Love Children,” which will be published in the fall. Jacobs of the Feminist Press described it as semi-autobiographical. Like her last novel, “In the Name of Friendship,” it offers a lighter view of men and women -- not because she had grown soft in her old age.

“The women of my generation raised feminist sons,” she told the London Guardian in 2006. “These men love their children, they are involved with them.

“But,” she added, “when it comes to the day-to-day nitty-gritty, women still do almost all the work.”

In addition to her daughter, French is survived by a son, Robert.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.