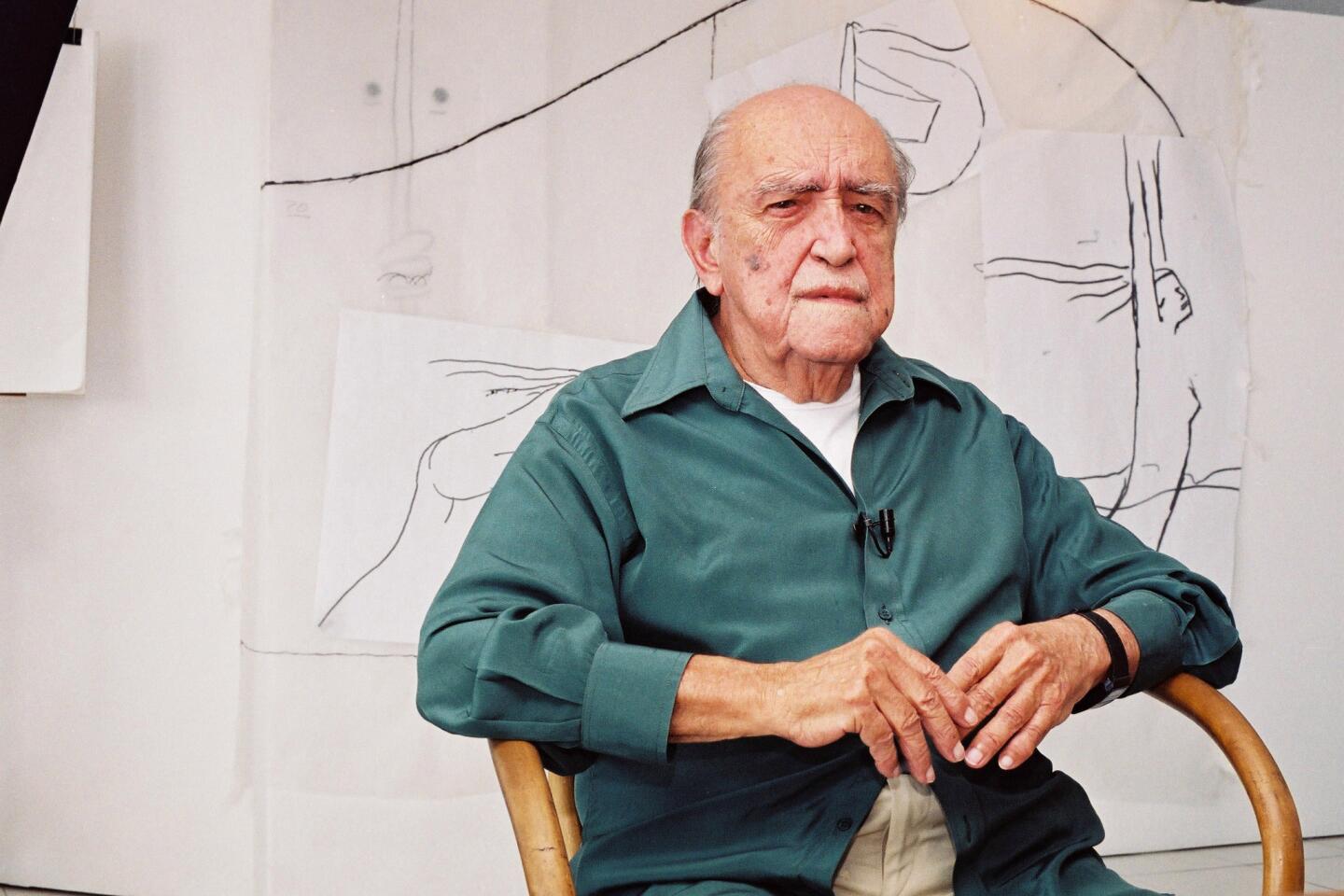

Oscar Niemeyer dies at 104; modernist Brazilian architect

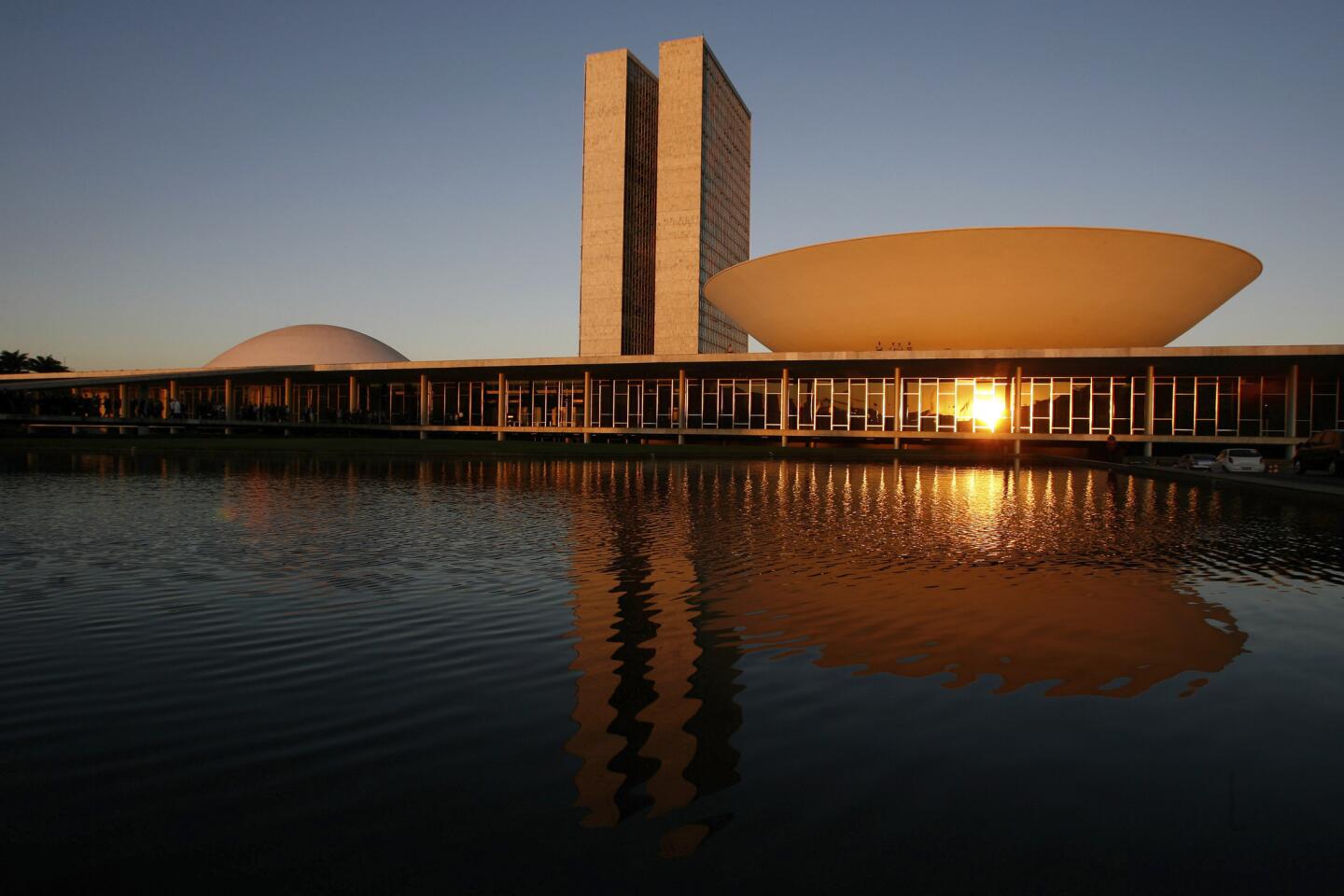

Oscar Niemeyer, the architect whose soaring buildings form the heart of Brasilia, the instant modernist capital built in the wilds of Brazil in the late 1950s, has died. He was 104.

Niemeyer, who had outlived his contemporaries to become the world’s oldest practicing architect of international stature, died Wednesday at a Rio de Janeiro hospital. The cause was a respiratory infection, a hospital spokeswoman told the Associated Press.

During his long and productive life, Niemeyer was revered as well as ridiculed for his daring designs, but the creativity and sheer volume of his works ultimately spoke for him. In 1988, at 80, he shared architecture’s biggest prize, the Pritzker.

PHOTOS: Oscar Niemeyer’s life and work

Niemeyer, a diminutive, soft-spoken man, worked well into his 90s in a Rio de Janeiro penthouse office with a stunning view of Sugar Loaf Mountain and overlooking Copacabana Beach. Hundreds of projects came into being kindled by this view.

Many of his designs began with a quick sketch that embodied his love of the curve — from Einstein’s universe, to the sinewy white beach that he gazed at nearly every day, to the voluptuous women he so loved to watch walking along that beach.

These women, he often said, were his inspiration.

“Curves are the essence of my work because they are the essence of Brazil, pure and simple,” Niemeyer told the Washington Post in 2002. “I am a Brazilian before I am an architect. I cannot separate the two.”

A passionate man, he lived in protest of the right angle “and buildings designed with the ruler and the square.” His politics were also those of protest — he became a communist in the 1940s because of his anger over the inequality he saw around him, and he was a longtime friend of Cuba’s revolutionary, Fidel Castro. His designs — especially of Brasilia — were partly an attempt to push his country toward egalitarianism, bringing rich and poor together through housing projects and public spaces.

A few years after Brasilia was completed, when a rightist military coup in 1964 not only destroyed Niemeyer’s dreams of a just society in Brazil but also took away his sponsors, he fled to Algiers and then Paris. In the city, he had an office on the Champs Elysees and met Pablo Picasso, Jean-Paul Sartre and many other notables and, he later recounted, lived a hedonistic life far away from his wife, Annita. He returned to Rio in the late 1970s.

Oscar Ribeiro de Almeida de Niemeyer Soares was a Carioca — a native of Rio — whose heritage was Portuguese, Arab and German. Born Dec. 15, 1907, he was the son of a businessman and his wife who lived in Laranjeiras, a quaint, hilly neighborhood within the city.

While at the National School of Fine Arts, from which he graduated in 1934, Niemeyer worked with architect and urban planner Lucio Costa, who would lead Niemeyer to projects that would make his name in international architecture.

Costa, the master planner of Brasilia and an early proponent of Brazilian modernism, at first was unimpressed when the young draftsman joined his firm. Before long, they were working with Swiss-born architect Le Corbusier — who was in Brazil as a design consultant to the government — on the defiantly modern design for the Ministry of Education and Health Building in Rio. The building, which incorporated Le Corbusier’s signature “brise-soleil” louvers to shield it from Brazil’s intense sunlight, became a symbol of the new architecture in Brazil.

Le Corbusier would greatly influence Niemeyer, instilling in him a sense of fluidity, spontaneity and what David Underwood, writing in “Oscar Niemeyer and Brazilian Free-form Modernism” (1994), called jeito — “the lightness of touch, the graceful elegance of form and the movement inherent in the sauntering ‘Girl from Ipanema’ celebrated in the best of Brazilian modernism.”

While Le Corbusier opened doors to creativity, however, Niemeyer saw his work as very distinct from his mentor’s. As he told The Times: “He posited the right angle. I posit the curve.”

In bringing to life his sensuous designs, he relied on what was then a new and versatile material — reinforced concrete — which he pushed to its limits, especially at load-bearing points, he wrote in a 2003 essay for Deutsches Architektur Museum, “which I wanted to be as delicate as possible so that it would seem as if [they] barely touched the ground.”

The first Niemeyer structure built was a maternity clinic in Rio in 1937. His first major project, commissioned in 1940, were buildings for Pampulha, a then-new suburb of the southeastern city of Belo Horizonte, including a yacht club, casino and a church so avant-garde in design that church officials refused to consecrate it for 16 years.

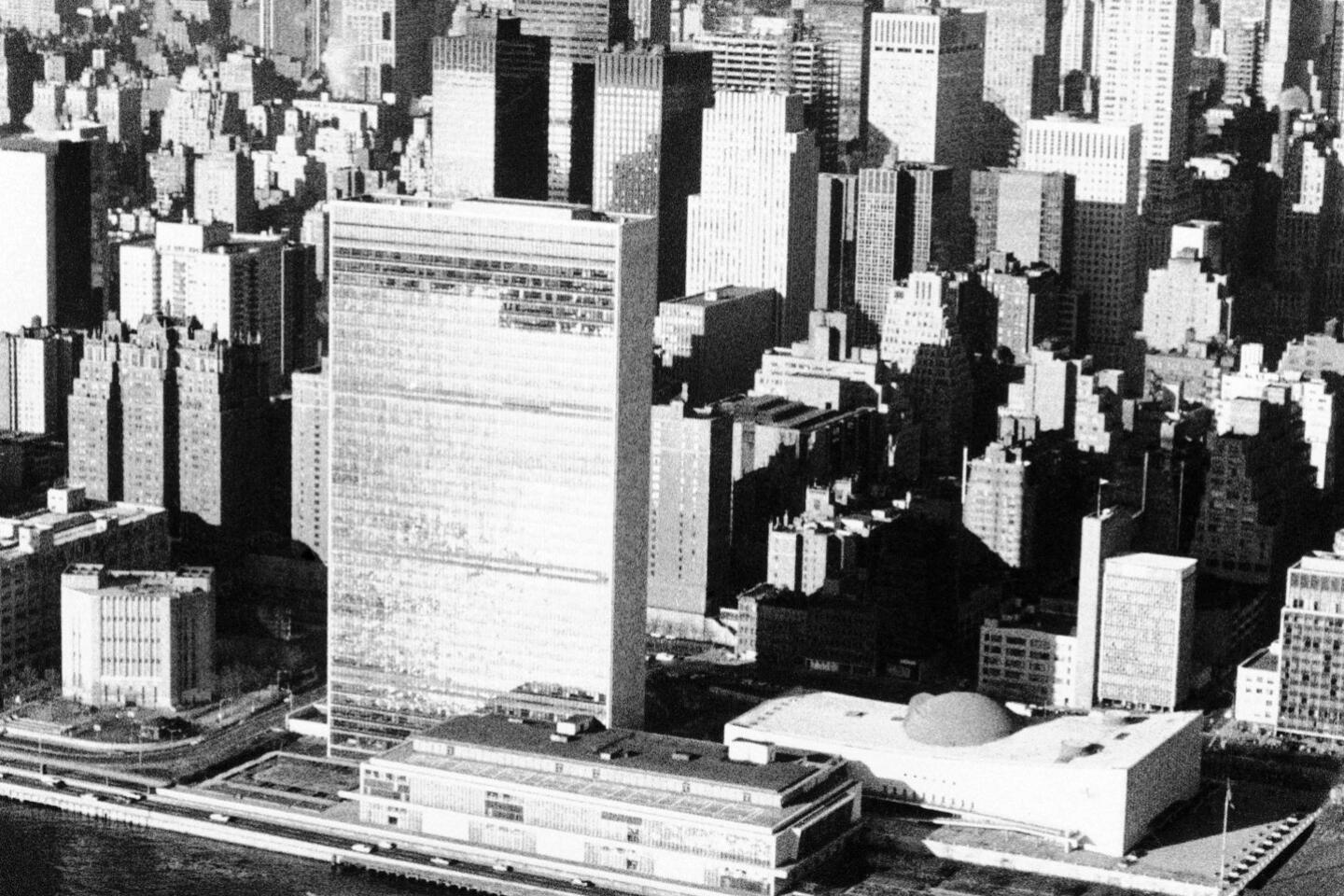

With Costa, Niemeyer also designed the Brazilian Pavilion at the New York World’s Fair in 1939, and Niemeyer influenced the ultimate design of the United Nations headquarters while serving as Brazil’s design consultant in 1947.

In time, his portfolio would include a postwar housing project in Berlin; the universities of Constantine and Algiers in Algeria; the French Communist Party headquarters in Paris; the Cultural Center of Le Havre, France; and the Mondadori headquarters in Milan.

He also designed the Strick House in Santa Monica— thought to be his only residential commission in the United States.

He will perhaps be best remembered for Brasilia, the bold project launched by Brazilian President Juscelino Kubitschek in 1956 in an effort to unify his vast country and move it forward half a century in a mere five years.

Kubitschek commissioned Niemeyer and Costa to oversee his dream of moving Brazil’s capital from coastal Rio to a nearly uninhabited high central plain more than 700 miles away. Niemeyer had described it as “a dismal patch of wilderness.”

Costa developed the master plan, which from the sky resembled an aircraft, with public buildings in the body of the craft and housing in the north-south wings. Niemeyer designed the major public buildings, including the Alvorada Palace, the cathedral and the Supreme Court and Congress buildings.

Niemeyer began his work on Brasilia by designing the glass-and-concrete cathedral, which resembles an old-fashioned woman’s corset with stays cinched around the middle. To heighten the drama for worshipers, Niemeyer designed a dark subterranean entrance hall from which one emerges into a light and airy nave.

“Instead of looking out into the emptiness, you look upward, to where the Lord is waiting,” the lapsed Catholic told Newsweek in 2002.

Within four years after construction began, Brasilia was established as the country’s seat of government — a feat that took 40,000 workers and ultimately broke the country’s treasury.

Though monumental in its grandness, Brasilia has had its share of ardent critics, including Robert Hughes, who had called it a “utopian horror.”

Even Niemeyer was disappointed that Brasilia did not fulfill his idealistic dream of one bright and equal city full of the future. Twenty years after it was built, Niemeyer said that the poor “see the beauty of Brasilia through binoculars.”

But to other criticisms — for example, that not all of Brasilia’s buildings are functional or lasting — Niemeyer verbally shrugged. “It’s not enough to be functional,” he told The Times.

His goal was to astonish, to inspire, to make his buildings “beautiful and spectacular so that the poor can stop to look at them, and be touched and enthused.”

Neimeyer’s wife of 75 years, Annita, died in 2004. Two years later he married his former secretary, Vera Lucia Cabreira. With his first wife he had a daughter, Anna Maria. His survivors include many grandchildren, great-grandchildren and great-great-grandchildren.

Luther is a former Times staff writer.

PHOTOS: Oscar Niemeyer’s life and work

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.