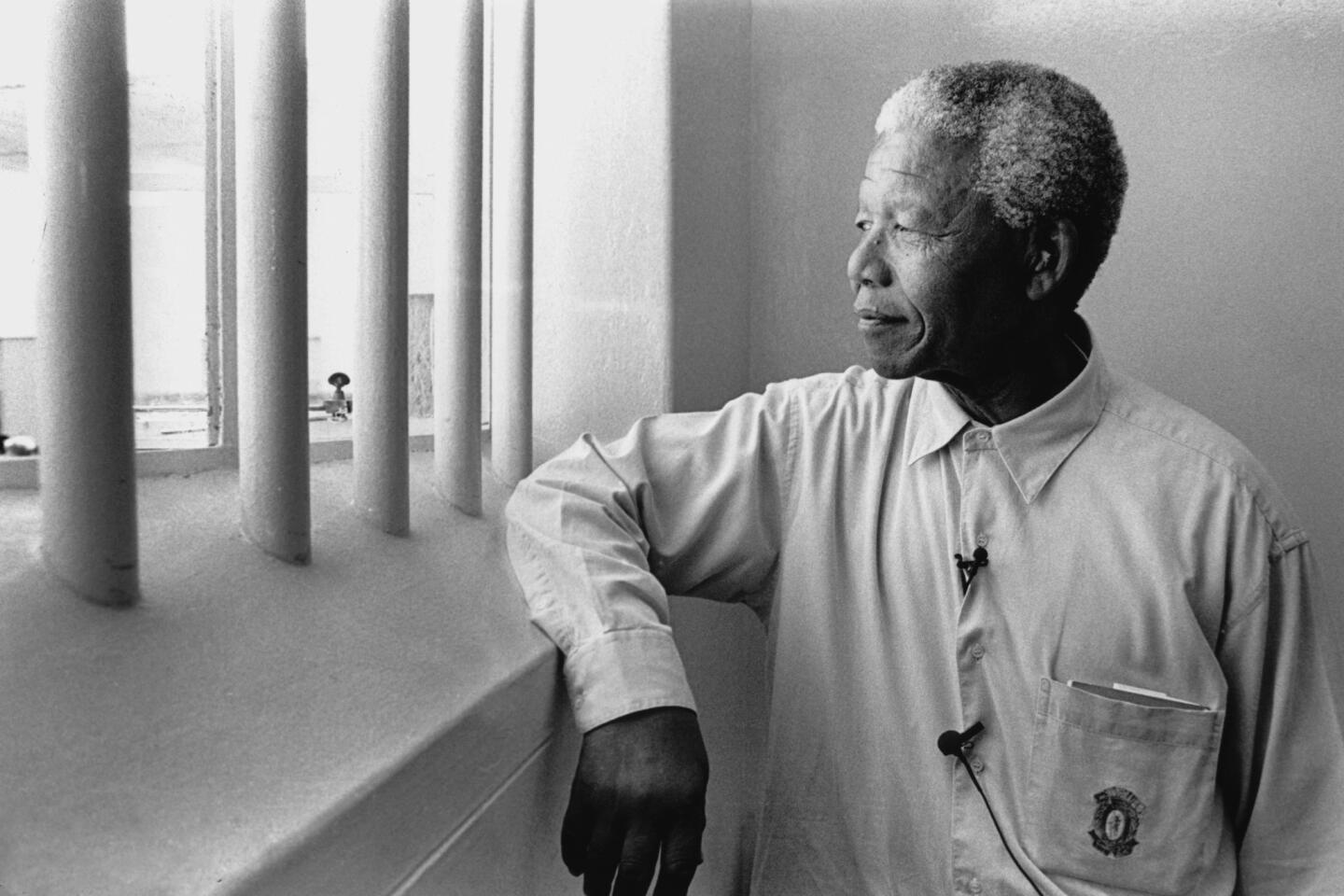

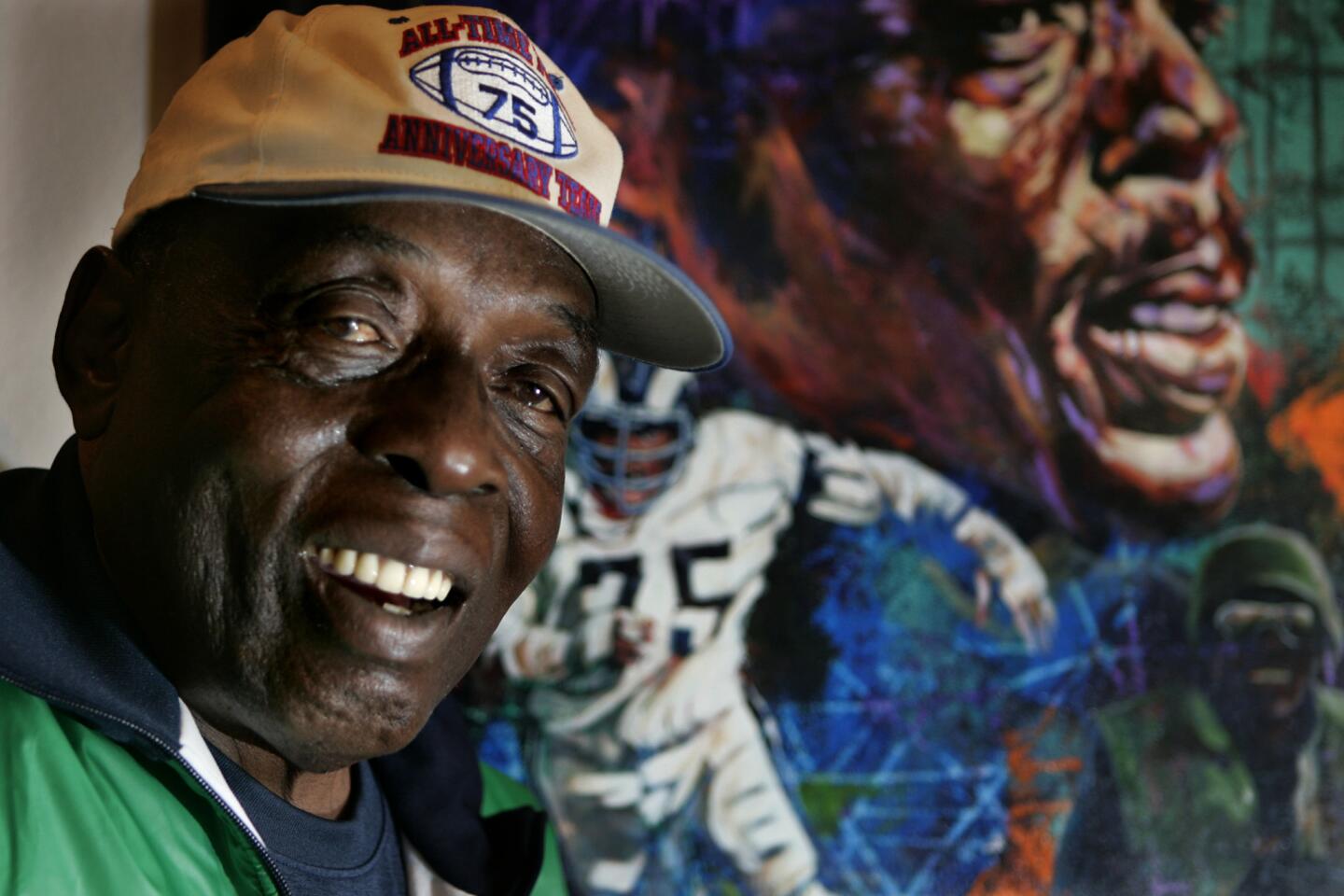

Walt Sweeney dies at 71; offensive guard for the San Diego Chargers

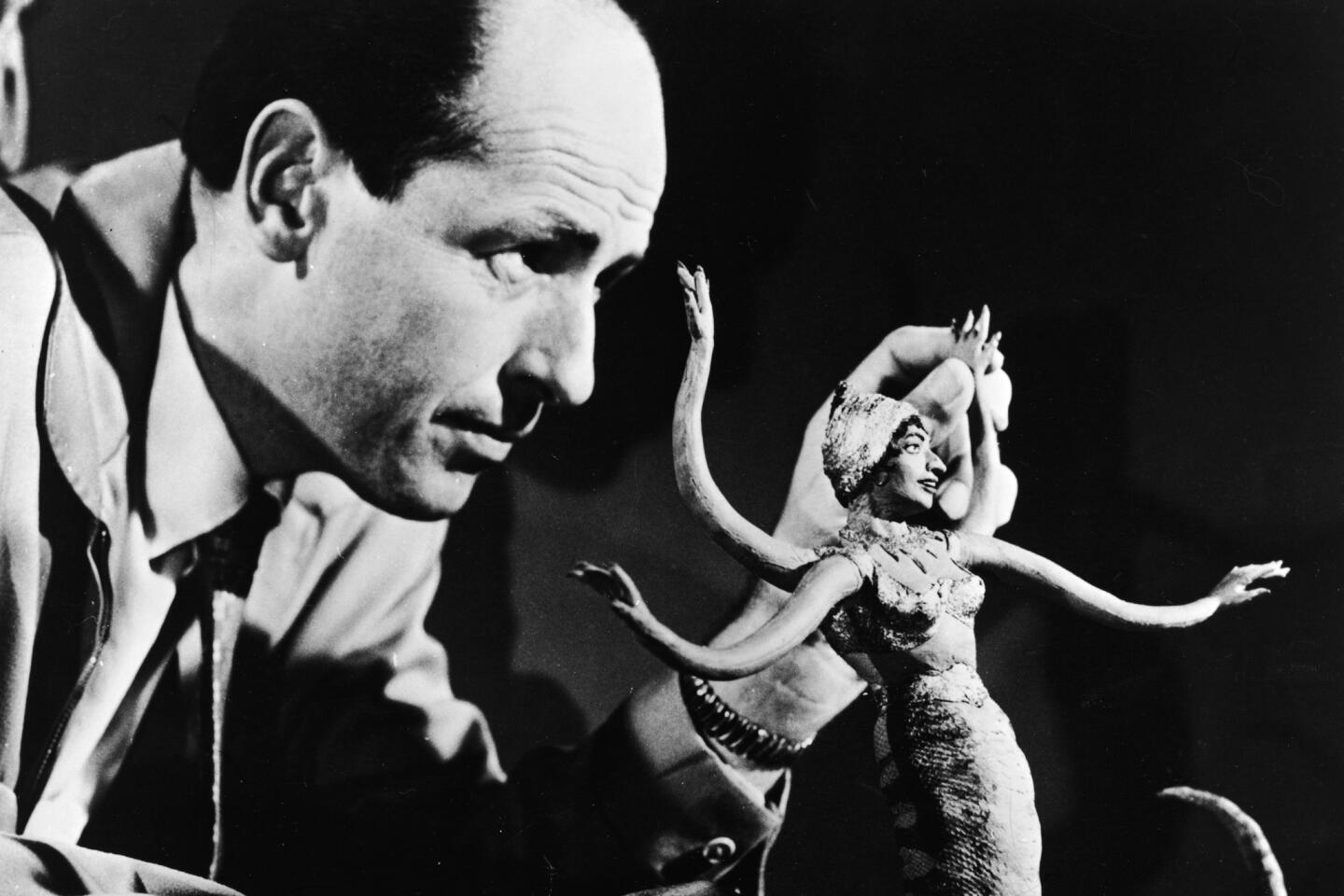

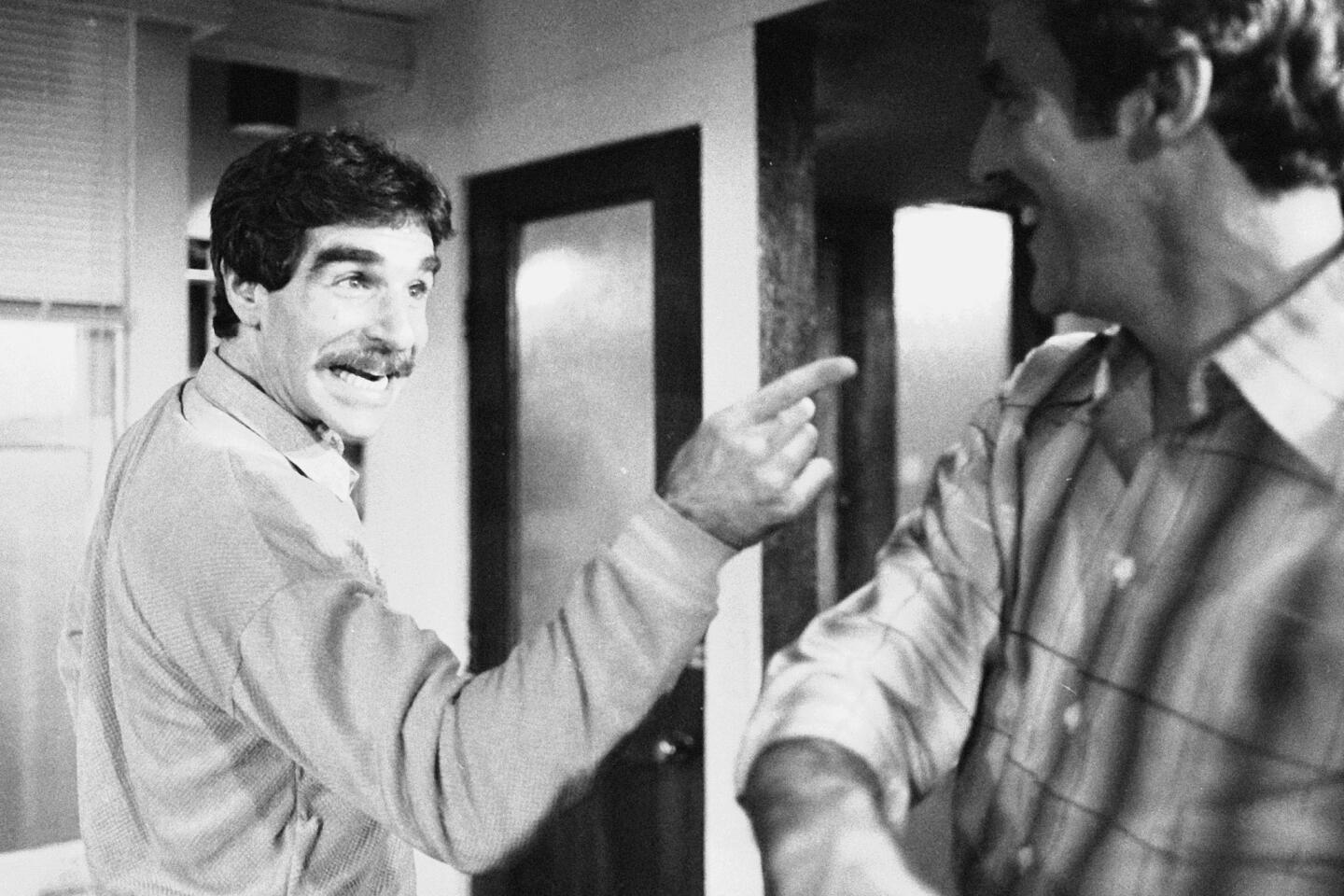

In his first game in 1963 with the San Diego Chargers, Walt Sweeney established a pattern that would mark his 13 seasons as a star in professional football.

Even though it was only an exhibition, Sweeney played with a fearsome aggressiveness. As a special teams player, he raced down the field ahead of the veterans, making several tackles over the course of the game and becoming a fan favorite as the Chargers beat the Oakland Raiders.

But there was something the fans did not know: Sweeney, then a 22-year-old first-round draft choice from Syracuse University, was so high on speed that his heart would not stop pounding after the game.

In 11 seasons as an offensive guard with the Chargers and two with the Washington Redskins, Sweeney continually used a variety of drugs to build bulk and endurance — as well as alcohol and marijuana for fun and relaxation.

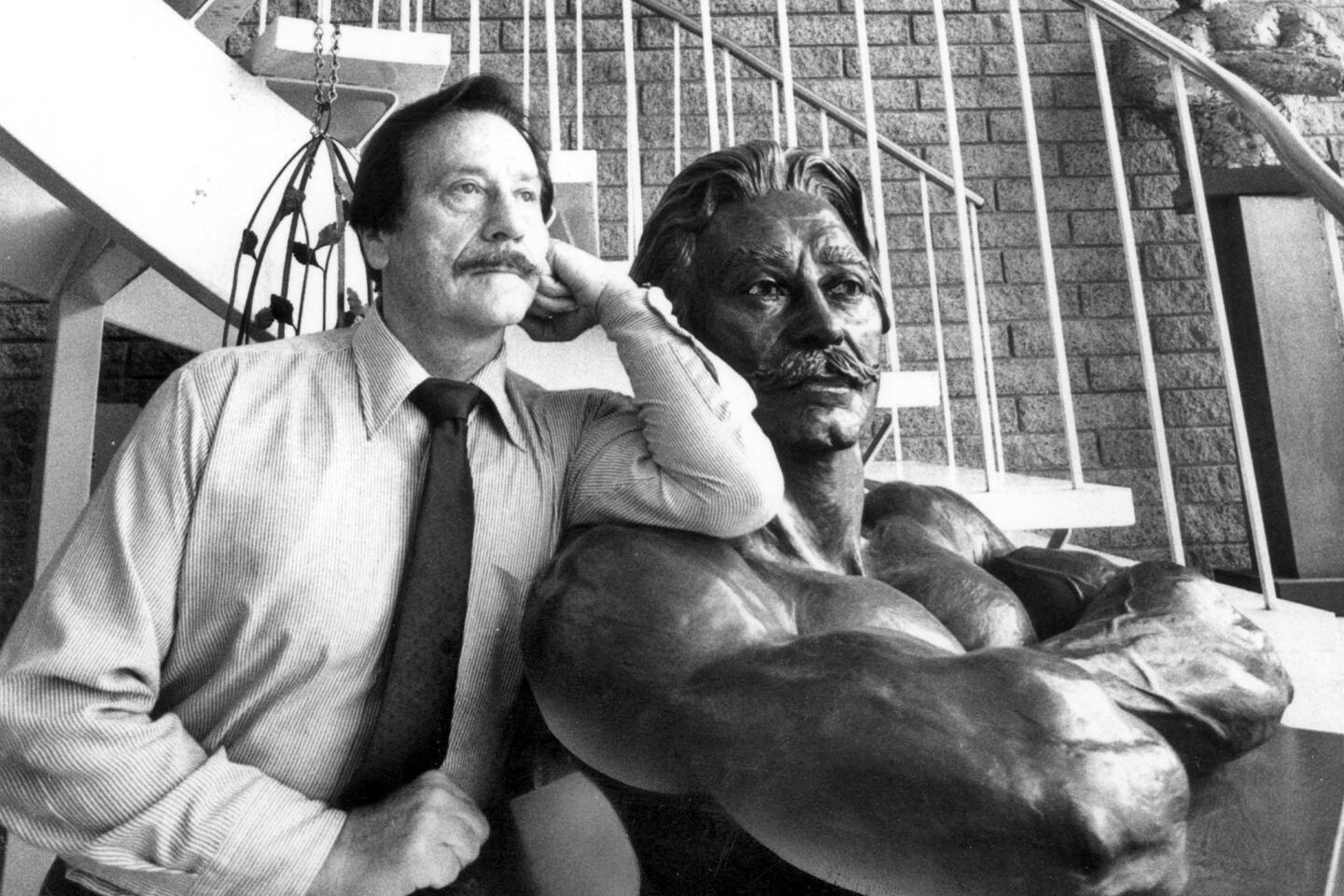

At 6 feet 4, 256 pounds, he was so intimidating that Merlin Olsen, the Los Angeles Rams’ Hall of Fame defensive lineman, said famously that if he had to play against Sweeney every week, “I’d rather sell used cars.”

When his playing days were over, Sweeney’s life continued to be dominated by his addiction to drugs, which he blamed on the masters of football and a win-at-any-cost attitude.

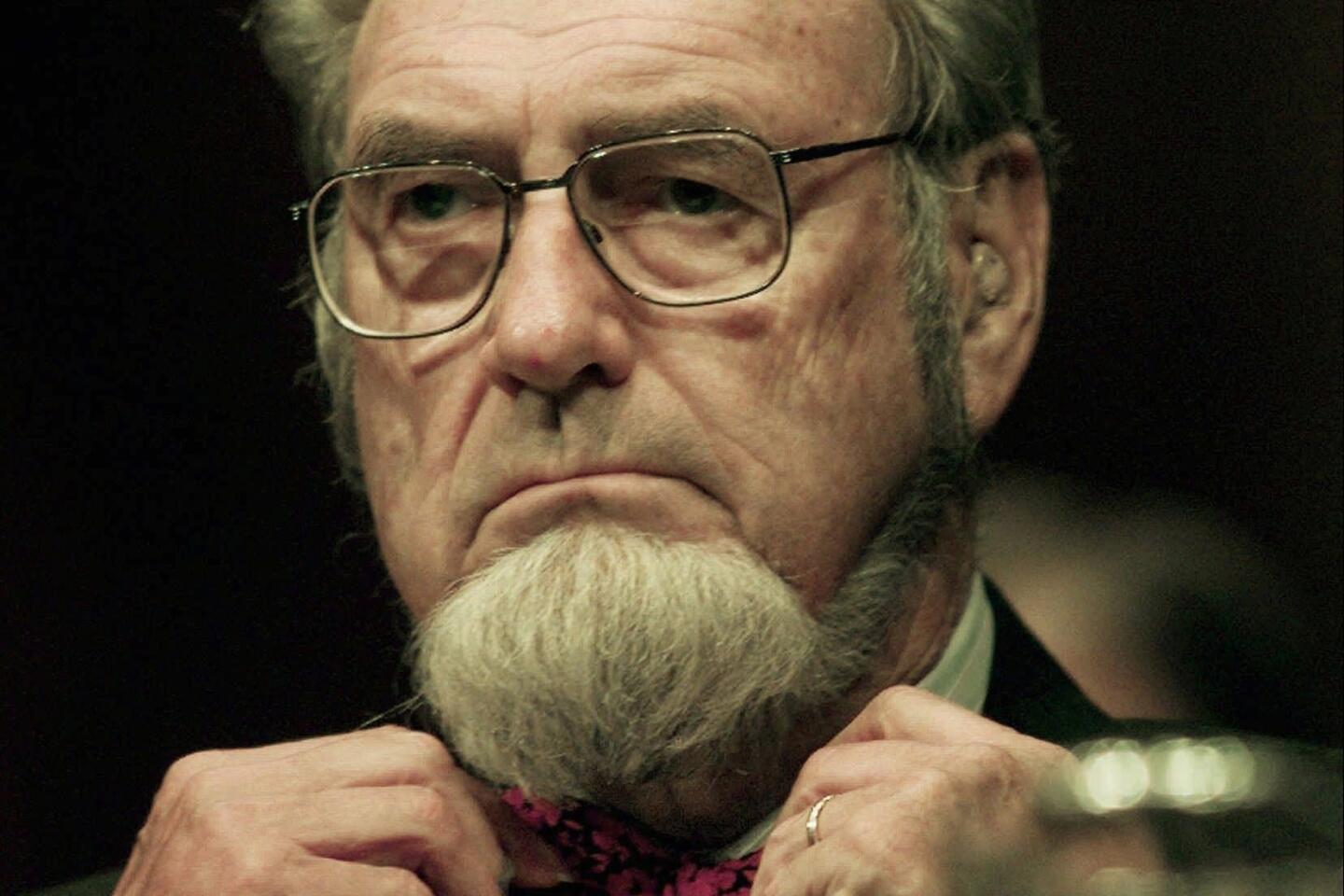

“The NFL fed me full of drugs for years and years and years,” Sweeney told The Times in 1997 while in the midst of a lawsuit against the trustees of the NFL pension plan. “Basically, I feel it’s ruined my life.”

Sweeney lost his lawsuit, with an appeals court ruling that his disability could not definitely be traced to his football years. But even in losing, Sweeney pioneered the concept, now the basis of numerous lawsuits, that the National Football League needs to show greater concern for retired players.

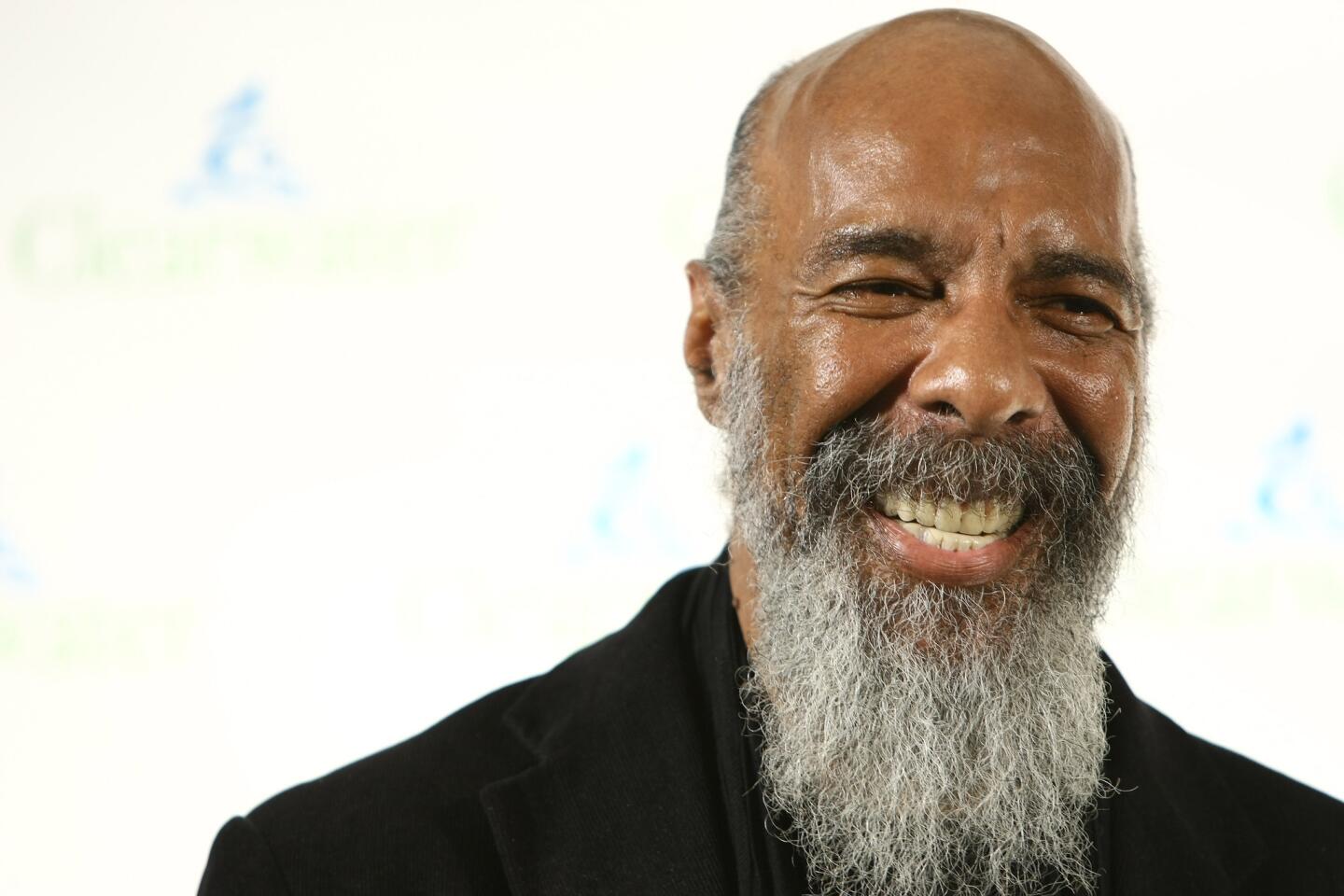

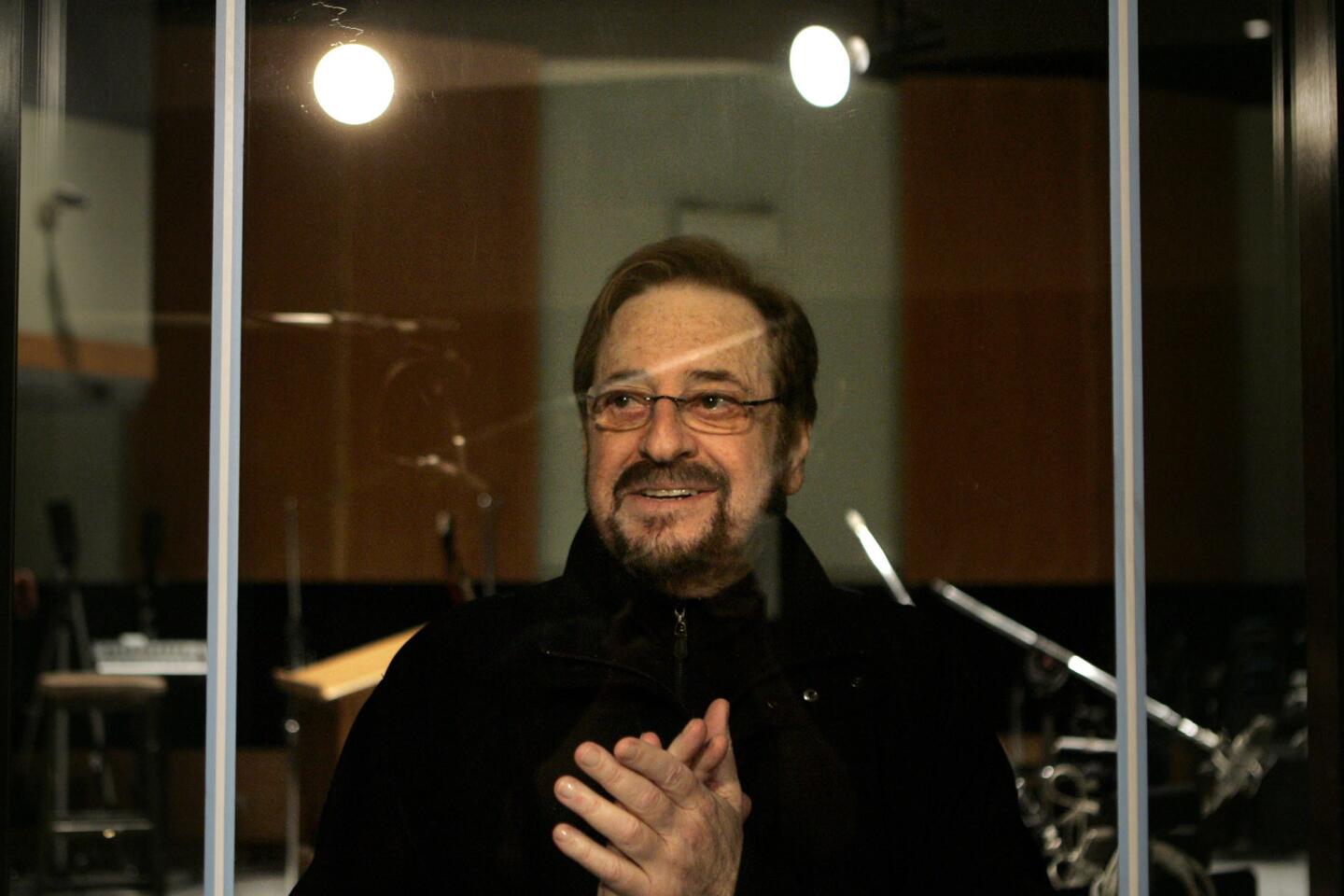

Sweeney died Saturday, on the eve of the Super Bowl, of pancreatic cancer at his home in San Diego, his family announced. He was 71 and had been diagnosed with the terminal illness just weeks earlier.

Walter Francis Sweeney was born April 18, 1941, in Cohasset, Mass. His was a large working-class Irish-Catholic family where alcohol and rowdiness were standard.

With the Chargers, Sweeney played for a series of task-master coaches, including Sid Gillman, whom he admired as a father figure. When drugs were offered as a path to success on the field, he did not hesitate.

“I was full of fear,” Sweeney said. “I didn’t want anybody to hurt the quarterback. Fear is a good motivator, but it stresses you out.”

Be it because of fear or drugs, the Chargers went 11-3 in Sweeney’s first season, beating the Boston Patriots, 51-10, in the American Football League championship game. It remains the only championship season for the Chargers in either the AFL or NFL.

In 1974 Sweeney was among several Chargers fined by the league for drug use. Later, the team’s unpaid analyst, Dr. Arnold Mandell, wrote “The Nightmare Season” about the rampant use of drugs by Chargers during the 1973 season.

Sweeney said that the fines, Mandell’s book and negative news stories did little to reduce drug use among players during his years on the field, which ended in 1975 after a severe knee injury while playing for George Allen’s “Over the Hill Gang” in Washington.

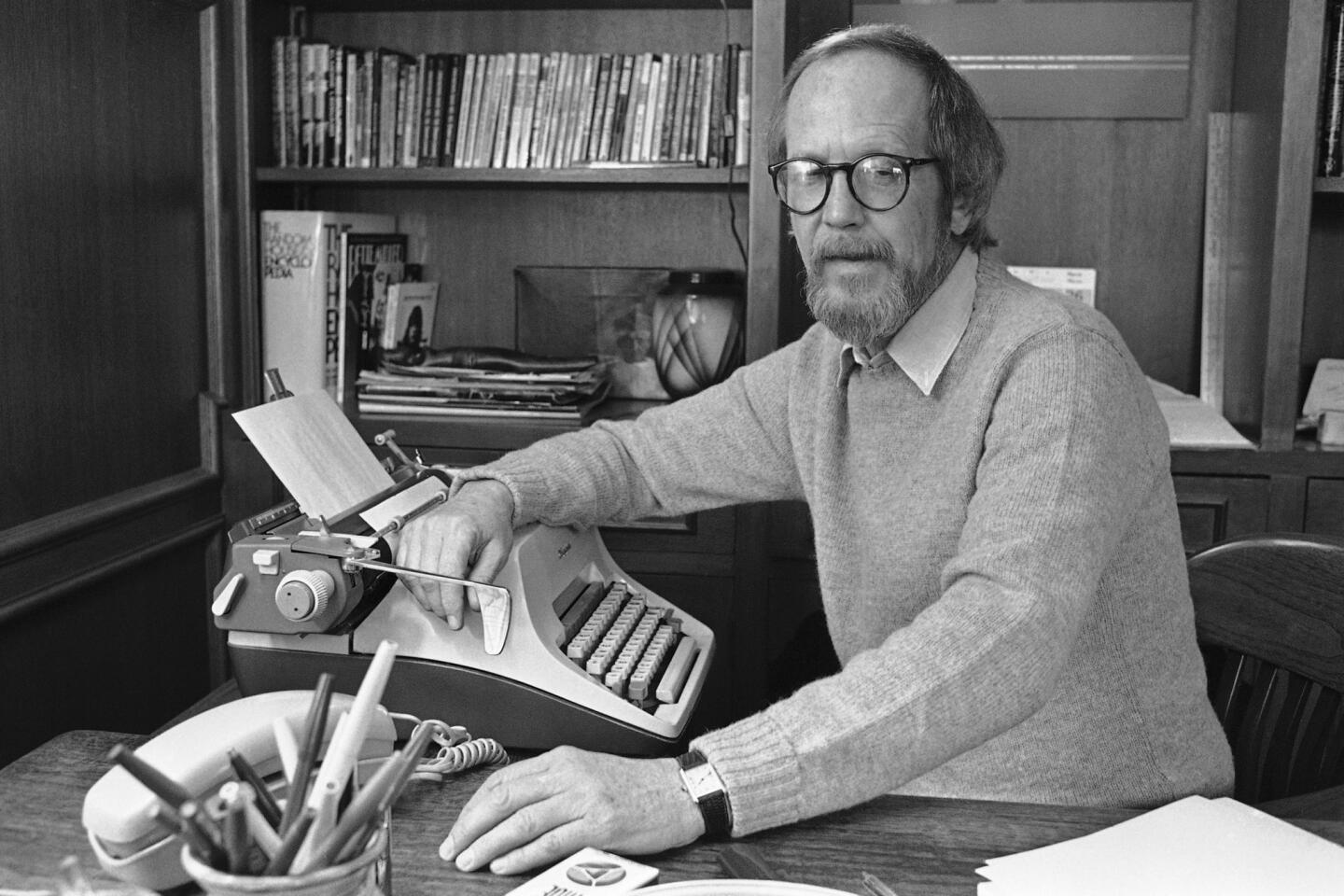

Last year, Sweeney published his autobiography, “Off Guard,” written with veteran sports author Bill Swank. It is a candid account of Sweeney’s upbringing, his years as a hard-drinking college player, and then the pressure and joy of joining the fledgling AFL in the years before the merger with the NFL.

Sweeney also detailed his problems after he left football: the lost jobs, the run-ins with police, failed marriages, the sense of hopelessness, and then the losing legal battle. Football had also taken a physical toll: four knee replacements and a hip replacement.

For a while he was a drug counselor at a San Diego hospital, appearing with Nancy Reagan in her “Just Say No” campaign. But he continued to take drugs. “I could talk a good game, but I couldn’t do it myself,” he said.

In “Off Guard,” Sweeney says that, after repeated failures at rehab clinics, he finally kicked his addiction in recent years.

“I wish it was some sort of spiritual awakening,” he wrote, “but the fact of the matter is that I just got tired of fighting it.”

Sweeney, a member of the Chargers Hall of Fame, is survived by daughter Kristin and son Patrick. His third wife, Nanci, died last year.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.