Editorial: California needs to overhaul its protection of groundwater

There are many environmentally worrisome aspects of oil and gas production, and one is the injection of wastewater back into the ground. This process — a way of disposing of the contaminated water created during the drilling process — is done in conventional oil and gas drilling, and is even more common in fracking, which uses large amounts of water to fracture rock and release oil. The concern is that the injection process can end up poisoning the aquifers that provide drinking water.

Now, California has ordered oil and gas companies to stop injecting wastewater from their operations into 10 wells in the Bakersfield area, and is looking at about 100 more wells to see whether they should be closed too. It’s unknown how many if any of these wells involved fracking operations. But the state’s very lack of knowledge shows that it is a long way from the point where it should allow any large-scale expansion of fracking.

Decades ago, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency identified wells where water could be injected without poisoning potentially potable water. In 1981, it transferred the main responsibility for overseeing those wells to the state.

But in 2011, the EPA commissioned a study that found the state was doing an inadequate job. It wasn’t monitoring nearly enough wells, and it wasn’t inspecting the rest often or thoroughly enough. Some of the responsibility rests with the EPA, which released confusing information over the years about which wells were off limits to wastewater injection. The state Division of Oil, Gas and Geothermal Resources believes that many of the wells now under review were legally off-limits to wastewater injection under the EPA rules, but that the oil companies may have been unaware of that. As a result, the division reported this month, contaminated wastewater may have entered potential groundwater supplies.

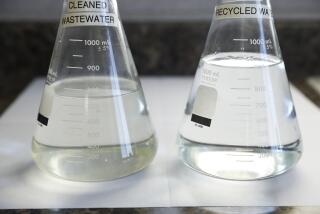

It’s deeply disturbing that the state’s inadequate oversight, coupled with what might have been confusing information from the EPA, has been allowing this over the course of years or even decades. But the current drought makes the issue particularly critical. The state is searching for new sources of water, including aquifers that might have been inaccessible in the past, or whose water was previously considered unsuitable for drinking but can now be purified using new technology.

There’s a final irony: The division became aware of this problem only because of SB 4, a 2013 law that required some regulation of fracking in California — and also ordered a review of existing disposal wells. What it showed is that the state needs to overhaul its protection of groundwater.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.