Editorial: The power to pardon is an important check, but the process needs more transparency

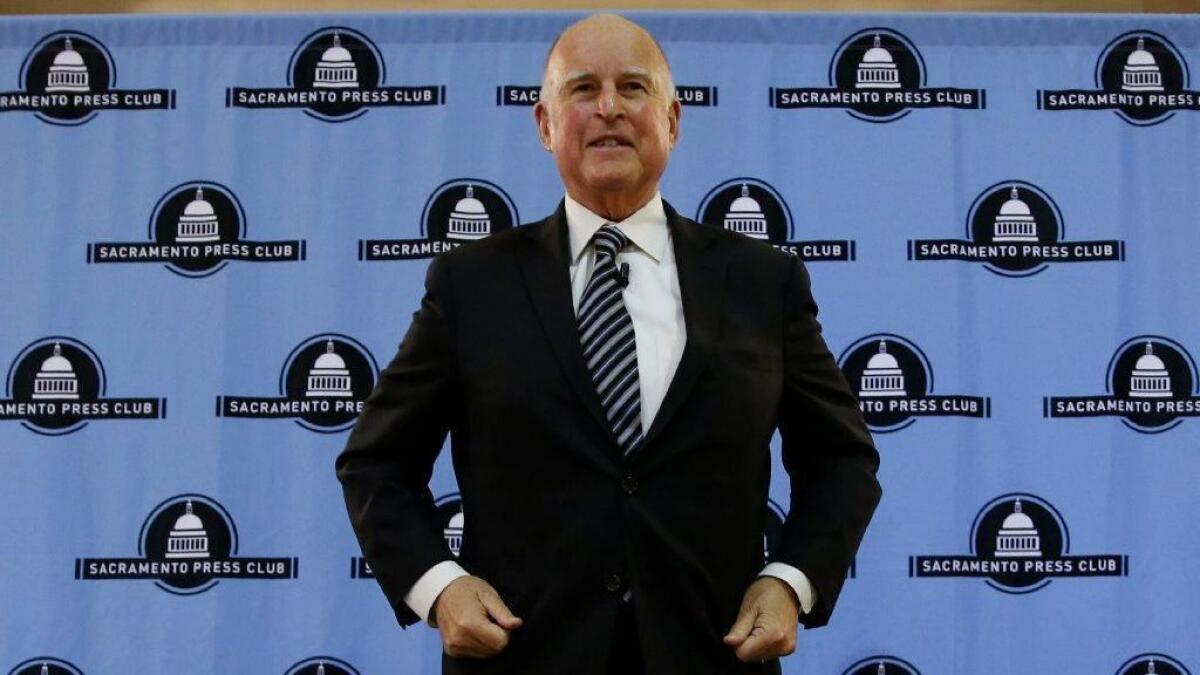

Gov. Jerry Brown’s bountiful grants of Christmas Eve clemency remind us that the justice system, when it is humane, extends to convicts a measure of hope along with an incentive to reflect, repent and rehabilitate.

Executive clemency balances the law — harsh and unyielding — with an element of human mercy and discretion.

Because discretion is tied to individual judgment, it is imperfect and can be abused, so the governor’s clemency power in California is curbed. He has authority on his own to pardon anyone convicted of a single felony, but the state Supreme Court can reject clemency for people convicted of multiple felonies. The court hadn’t done that in decades, but this year it rejected seven Brown requests.

The court’s action is not on its face unreasonable, given the number of applications for clemency that Brown granted. In the last eight years, he pardoned more than 1,000 convicted felons who had already served their time, and commuted more than 150 sentences of inmates, making them eligible for earlier parole or at least parole hearings. That’s pardoning and commuting on a scale unmatched by his predecessors. Yet his grants of clemency, when taken together with the court’s rejections, appear to demonstrate a functioning system of checks and balances.

Except for one very important missing link.

What was it about those seven requests — each of them for convicted murderers with multiple felonies on their records — that led the court to say “no,” while allowing clemency for other killers? The justices issued their rejections without public explanation, leaving no guidance to future courts or governors.

Earlier this year, the court warned that it would reject pardons and commutations that amounted to abuses of gubernatorial power. Fair enough. But the court failed to explain why pardoning one convicted murderer would be an abuse and pardoning another would not. The justices’ decisions set no binding precedents. They left their check on the governor’s power partially undefined.

On his end, Brown (like previous governors) offered little to explain why he granted some applications but denied others. That leaves the clemency process unnecessarily clouded by mystery. That’s an opportunity lost at precisely the time when the nation could use some strong guidelines for and statements about executive clemency, checks and balances.

The federal system lacks California’s explicit check on the president’s pardoning power, and President Trump has made the most of his unfettered discretion. For example, last year he pardoned Joe Arpaio, the former sheriff of Maricopa County, Ariz., and a staunch Trump political ally, before Arpaio could be sentenced on his conviction for criminal contempt of court. That’s a sharp distinction from Brown’s pardons, which affect only convicted criminals who have served their sentences but otherwise would have continued to be punished for life — by laws and practices that, for example, prevent them from earning professional degrees or licenses, or otherwise regaining their rights as citizens because of their criminal records. Ditto for the governor’s commutations, which may reduce but do not negate criminal punishment.

But Arpaio’s crime was a misdemeanor, and he may not have been required to serve any time behind bars. More disturbing are Trump’s statements that he’d consider pardons for former national security advisor Michael Flynn and former Trump campaign chairman Paul Manafort. D There’s no point prosecuting people close to me, the president is in effect saying, because I’ll just obliterate the conviction.

Enter the Fray: First takes on the news of the minute from L.A. Times Opinion »

The president’s clemency discretion is subject to serious abuse. Trump’s statements about Flynn and Manafort do not enhance or humanize the criminal justice system but rather undermine it.

Admittedly, clemency is subject to abuse in California too. Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger, on his final day in office in 2011, commuted the murder sentence of Esteban Nuñez, the son of his ally and former Assembly Speaker Fabian Nuñez. Schwarzenegger argued that the sentence was unfair, but he also acknowledged that he acted as a favor to his friend. The state Supreme Court had no power to reverse that particular misuse of discretion because Nuñez had not been convicted of multiple felonies.

Exercised properly, the governor’s clemency power is itself a check on the excesses of the criminal justice system — but only for a limited number of applicants, and for whom the relief is granted with at least some degree of subjectivity.

That’s the nature of discretion. It is by definition subjective. It remains an essential part of the criminal justice system, whether exercised by prosecutors, judges, parole boards or the governor — but it operates best when it is accompanied by a greater degree of transparency.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinionand Facebook

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.