Editorial: Really, justices? Even <i>more</i> money in politics?

On Wednesday, conservatives on the U.S. Supreme Court continued their project of undermining reasonable attempts by Congress to limit the corrupting influence of money in election campaigns. The same 5-4 majority that lifted limits on corporate political spending in the Citizens United decision struck down long-standing limits on the total amount a citizen can donate during an election cycle. As in Citizens United, the majority held that the restrictions violated 1st Amendment protections for political speech.

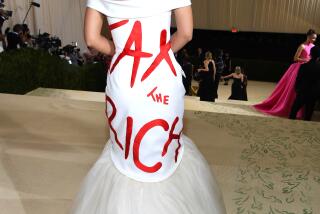

This decision does not disturb limits on how much a donor can give to a single candidate or committee (so-called base limits). Even so, it will open the floodgates for campaign donations by wealthy individuals. Before Wednesday’s ruling, a single donor was barred from giving more than $123,200 in total to federal candidates and party and other political committees. Now a donor will be able to contribute the maximum to as many candidates and committees as he likes (the ceiling for donations to a candidate is $5,200). That sort of largesse will not be ignored.

In an opinion signed by three other justices, Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. said that the aggregate limits couldn’t be justified as an anticorruption measure. Roberts also disputed the conclusion of a lower court (and of Justice Stephen G. Breyer in his dissent) that abolishing aggregate limits would make it easier for donors to circumvent the base limits as well.

But the focus on circumvention is too narrow. Even if a donor’s contributions are divvied up in a way that respects the contribution limits for each individual candidate, the overall financial commitment to the party and its candidates will leave both in the donor’s debt. The campaign reform group Democracy 21 notes that after Wednesday’s decision, a presidential nominee could form a joint fundraising committee and solicit a contribution of as much as $1,199,600 from a single donor for the election cycle. Does anyone doubt that the person who signed that check would expect special consideration from the candidate who solicited it?

Roberts was untroubled by the idea that mega-donors would receive special treatment in exchange for their largesse. The only corruption worth worrying about, he suggested, was quid pro quo corruption, which he defined as the “exchange of an official act for money.” But, as Breyer noted in his dissent, “the anticorruption interest that drives Congress to regulate campaign contributions is a far broader, more important interest.... It is an interest in maintaining the integrity of our public governmental institutions.”

That integrity is impaired when wealthy donors can purchase access to the people’s representatives by writing million-dollar checks. The court was wrong to give its blessing to such examples of “free speech.”

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.