King’s ‘Dream,’ and the reality

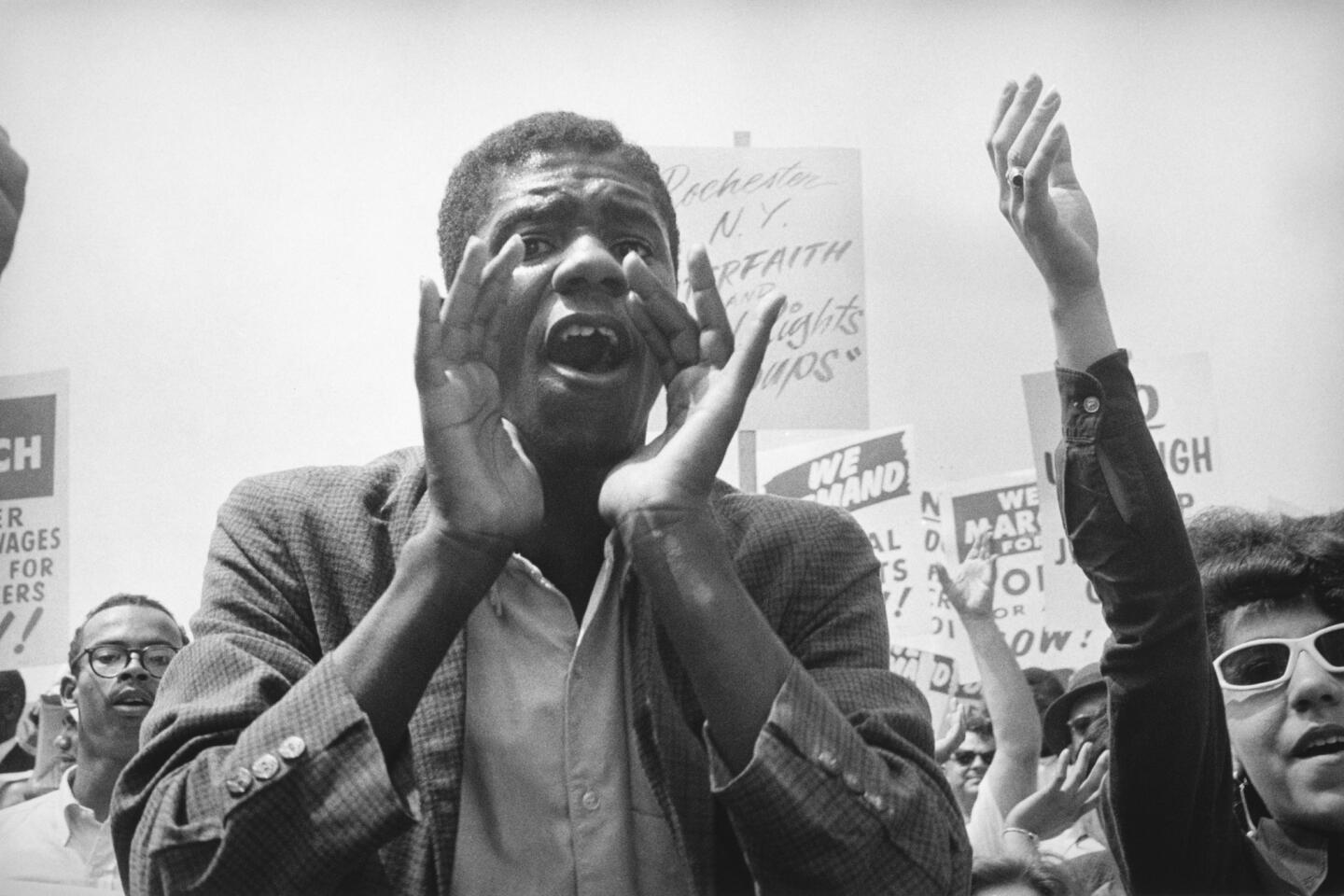

One hundred years separate Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address and Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech at the 1963 March on Washington. They are linked by the history of America’s defining struggle, and they are inseparable in imagery, as King delivered his historic address at the foot of the monument honoring Lincoln.

Neither speech immediately appeared destined to be historic. Lincoln wasn’t even the featured speaker at the dedication of the National Cemetery of Gettysburg. King had already spoken numerous times about the dream. The speech he set out to give 50 years ago Wednesday was dark and eloquent, certainly, but it was not until gospel singer Mahalia Jackson, standing behind King on the dais, urged him to “tell ‘em about the dream” that King took flight.

Lincoln’s address was delivered in wartime and included a deliberate note of modesty: “The world will little note, nor long remember, what we say here.” He was wrong about that. It has endured precisely because Lincoln’s message framed the Civil War as a test of democracy itself. Could a nation “conceived in liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal,” survive the challenge to its existence? Could any such nation “long endure”? Those were the stakes of the war he fought. He — and democracy — triumphed.

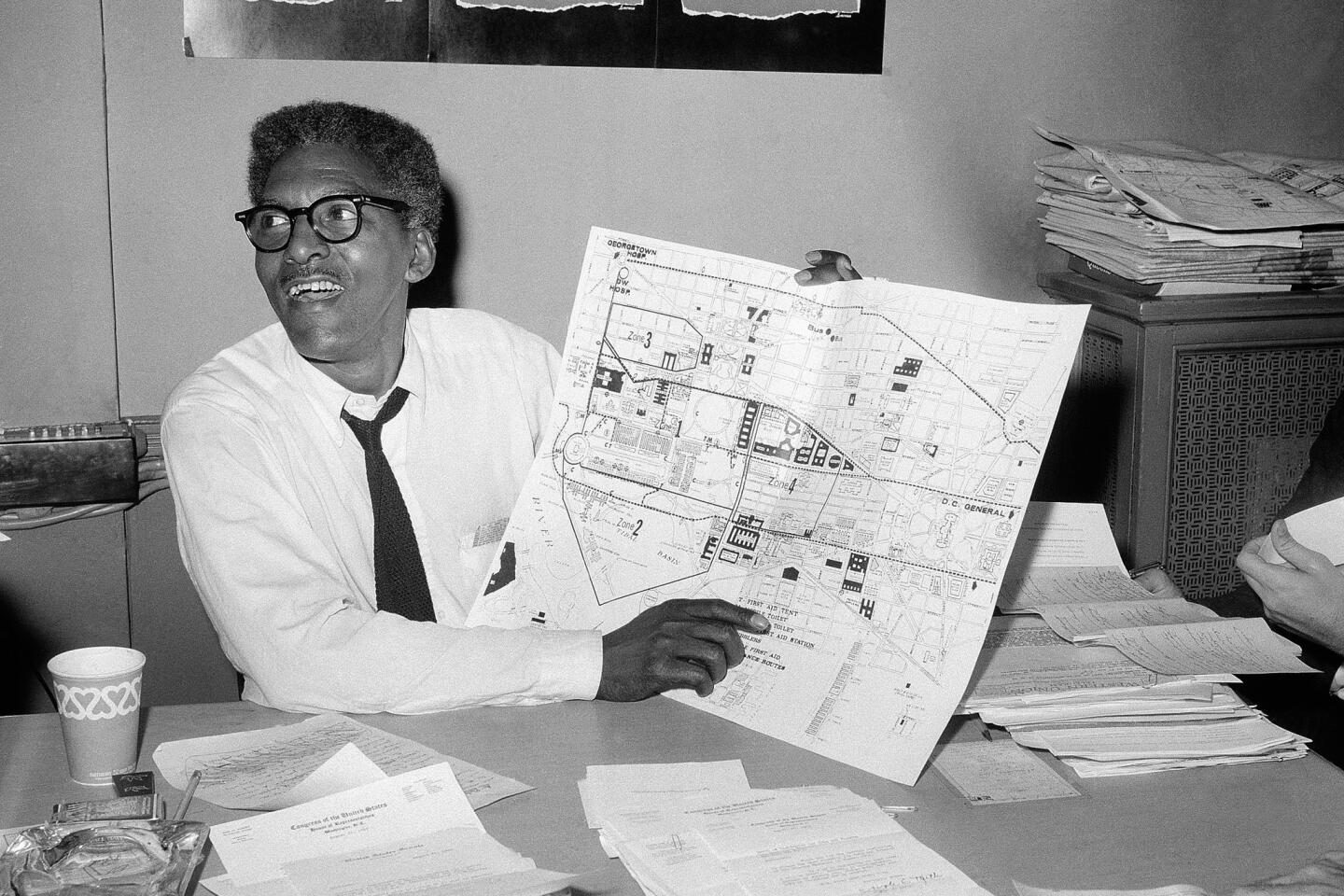

By the time King ascended the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, Lincoln’s war was long past and the promise of emancipation had fizzled into segregation and Jim Crow. As King put it: “It is obvious today that America has defaulted on the promissory note insofar as her citizens of color are concerned. Instead of honoring this sacred obligation, America has given the Negro people a bad check, a check that has come back marked ‘insufficient funds.’”

King did not live to see that check made good, and the struggle to make this nation’s actions live up to its creed continues. Gays and lesbians have made great strides in their fight for equality, but that work is unfinished. The debate over immigration too often descends into ethnic stereotyping. Even gender discrimination continues to stymie America’s full egalitarian ambitions.

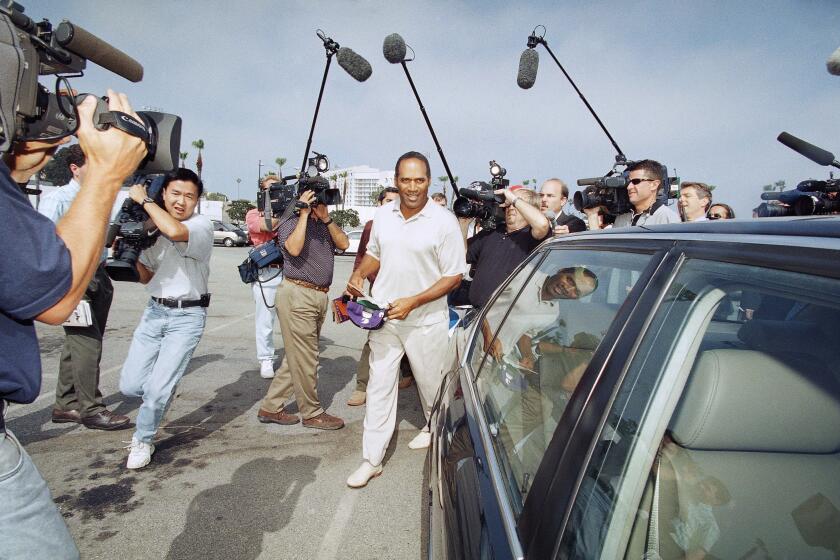

Wednesday, as during commemorations in the last few days of the momentous March on Washington, there will be a great deal of talk about how much of King’s dream has come true. In areas of the country where blacks and whites once were forced apart by law and custom, the descendants of slaves and slave owners regularly join at the table of brotherhood. Some of the most vicious redoubts of racism have evolved into pleasant, multicultural communities. Many children are, in fact, judged by the content of their character rather than merely the color of their skin. Indeed, it’s hard to imagine that even King would have dreamed that, five decades after he declared “the Negro is still not free,” the word “Negro” would be obsolete and a black man would be president.

And yet, no serious person believes that racism has been eliminated or that skin color is irrelevant. Poverty remains. Men and women of color bear too great a share of defending this country and receive too small a share of its benefits. Those troubles preoccupied King, and persist.

Just as Lincoln said it was up to the living to leave Gettysburg and honor those who died there by continuing to fight for the values they died for, so King told his listeners that they would have to leave Washington and return to the South, return to the ghettos of the North, “knowing that somehow this situation can and will be changed.” Neither used his speechto offer plans or proposals. Instead, they offered hope, resolve and, as King said, “urgency.”

In the years since, some of that urgency has faded — the result of progress, to be sure, but also indifference and a false sense of having completed the task. Witness, most recently, the Supreme Court, which in 1954 helped spur the civil rights movement by declaring school segregation unconstitutional. Just this year, declaring that “things have changed dramatically,” the court struck the portions of the 1965 Voting Rights Act that delivered much of the promise of equality.

President Obama has the daunting job of following King’s act. He will address the nation Wednesday from the same steps of the memorial. He may not offer a specific program, for no single program can bring this matter to a close. His task, instead, should be to resurrect the themes that bind the agonies of Lincoln and the wistfulness of King, to rekindle the urgency they summoned and to propel the great, continuing work of America — to extend equality to all, to make this a land that lives up to the proposition that all men are created equal.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.