Editorial: This was no bargaining ploy: LAUSD really is facing a financial cliff

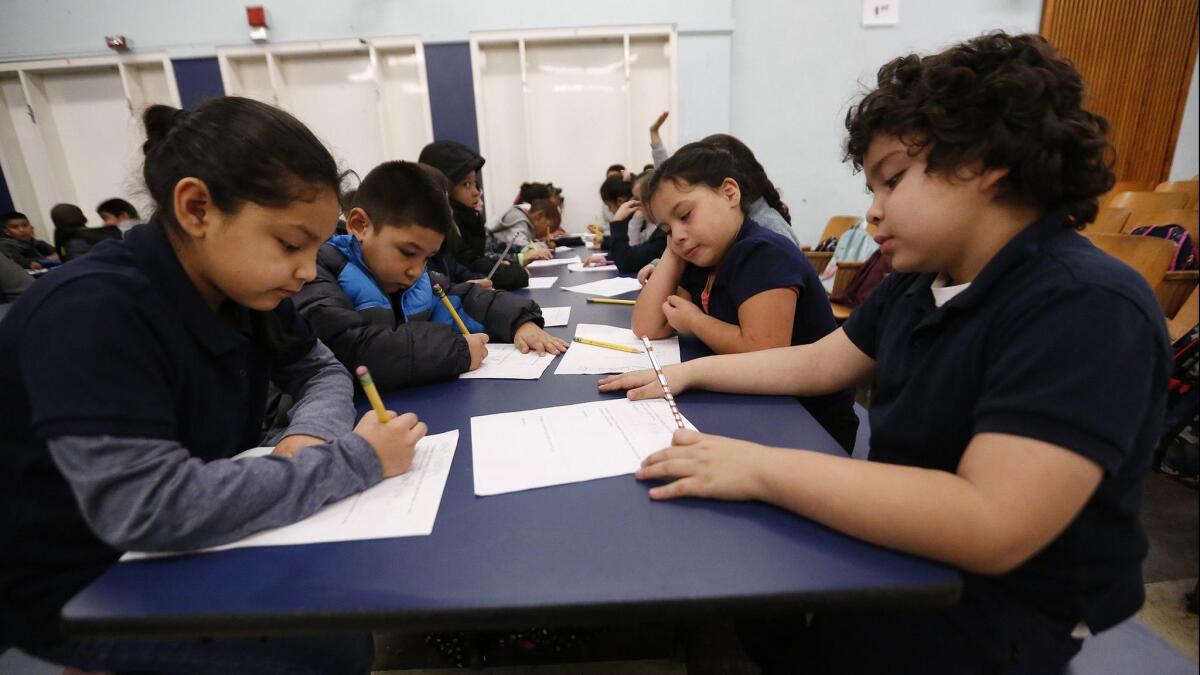

The teachers are off the picket lines, the kids are back at their desks and all is well with the Los Angeles Unified School District — for the moment.

But the very serious financial problems that schools Supt. Austin Beutner warned about continue to loom dangerously over the district. That wasn’t just alarmist rhetoric or a negotiating posture. An independent study commissioned under former Supt. Ramon C. Cortines laid out L.A. Unified’s shaky situation several years ago. The state has raised similar concerns. The Los Angeles County Office of Education weighed in with much the same message in November.

“We emphasize the need for the Board to recognize the long-term impact of the District’s structural deficit spending and are concerned that time-sensitive financial decisions are being postponed,” the county said in a letter to the district. Over the course of the next three years, “the unrestricted General Fund’s reserve is projected to decrease from $778.3 million to $76.5 million, a decline of 90.17 percent.”

The strike clearly increased awareness of the district’s financial needs.

Yet the district, desperate to resume instruction, its bargaining position weakened by the strong showing of parent and public support for the teachers union, has tentatively agreed to a plan to boost nursing, counseling and library staff at schools, and to reduce class sizes as well. What’s more, it agreed not to raise raise class sizes in the future even if it faces financial duress.

We’re all for better staffing. But there could be a sober reckoning ahead for the district. By lowering class sizes gradually over the next four years, the contract commits the district to more than $400 million in additional spending. At first the money will come from the district’s shrinking reserves, but over time that money will disappear. Meanwhile, the district’s enrollment is expected to continue to decline, reducing the per-pupil revenue the district receives from the state.

New infusions of revenue will be required. Those could come in the form of a local parcel tax, tentatively planned for placement on the 2020 ballot. Would it pass? The strike clearly increased awareness of the district’s financial needs; the question is whether the support built during an emotional week-long walkout would translate into two-thirds of voters agreeing to an additional long-term tax.

And not just any parcel tax proposal deserves public backing. A worthy measure would include clear language and restrictions on how the money can be spent, strong citizen oversight as well as guaranteed robust funding and authority for the district’s Inspector General to investigate spending and district operations.

Another potential source of revenue is the split-roll property tax initiative on the ballot next year. If it passes, it’s estimated that it would bring in more than a billion dollars a year for the district. If it fails, the district can still lobby for more funding from existing state sources, but with forecasts of an economic slowdown for California, this is an iffier proposition.

In other words, the new contract carries a strong element of calculated risk, and the outcome could be deeply problematic if the district loses the bet.

Enter the Fray: First takes on the news of the minute »

Unquestionably, California schools are underfunded, especially in comparison with those around the nation. The state’s per-pupil spending is in the bottom 10 in the nation; its student-to-teacher ratio is the fourth highest. The tentative deal has risks, but it has been struck and it needs to go through.

There are other options to pay for some of these new hires. The Board of Supervisors is looking at using its mental-health funds to help with nursing and/or counseling needs at the schools. If that moves forward, there should be clear rules for how the funding would be used; the supervisors also must consider that there are many students around the county who need these services, not just those enrolled in Los Angeles Unified.

Also, Mayor Eric Garcetti should be more involved in the schools, looking at ways to leverage city services at school sites.

It is great that Angelenos appear to recognize the needs of L.A. Unified and its students, and that the strike built support for better funded, higher quality schools. But it won’t come cheap.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion and Facebook

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.