Terrorism and American justice

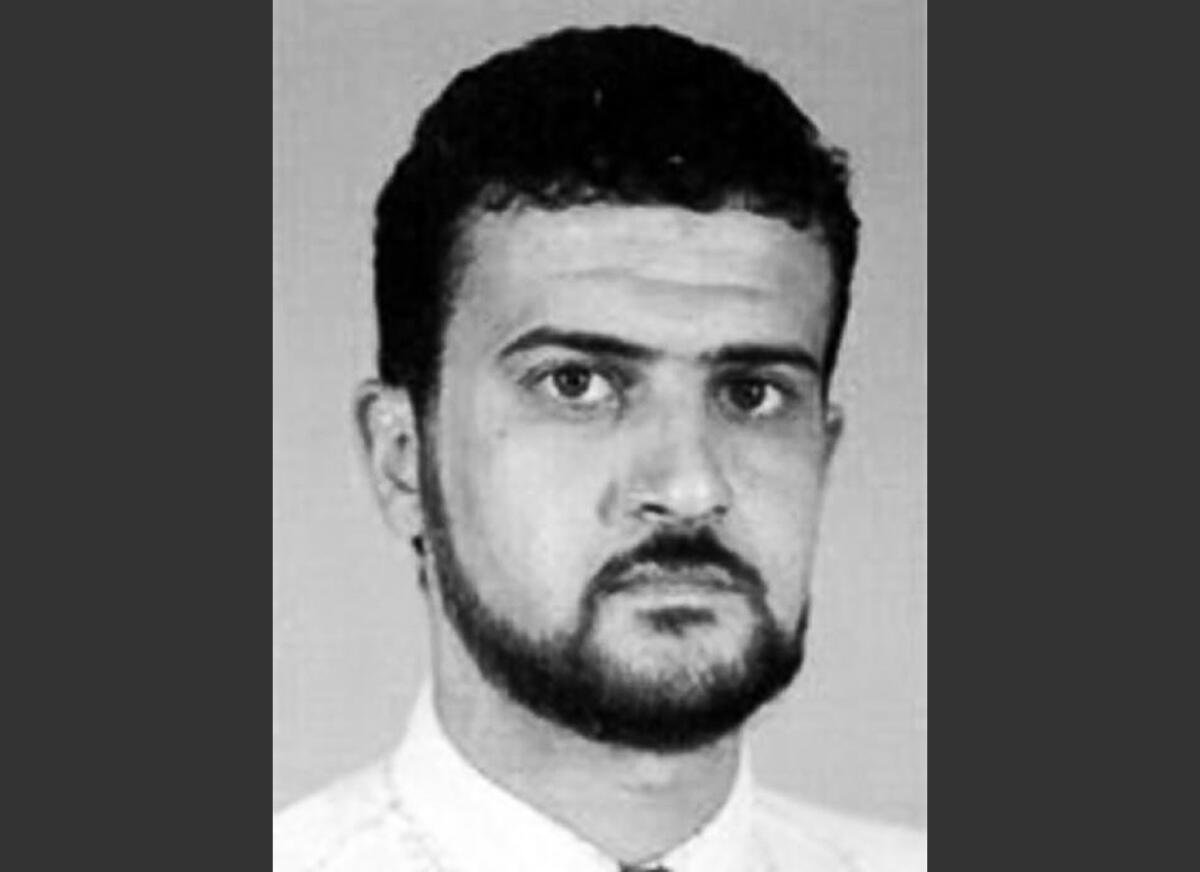

Thanks to a dramatic operation by U.S. military and intelligence agencies in Libya over the weekend, a suspected Al Qaeda figure indicted in the 1998 bombings of two U.S. embassies in Africa will finally face American justice. The capture of Abu Anas al Liby — and a raid the same day on the home of a leader of Al Qaeda’s affiliate in Somalia — suggest that the Obama administration is willing to incur the risks necessary to take some alleged terrorists alive. That may signal an overdue shift away from a controversial and counterproductive policy of targeted killings.

Nevertheless, if it is not handled correctly, the capture of Al Liby could provoke a backlash not only in Libya but also from nations that remember the George W. Bush administration’s policy of “extraordinary rendition,” under which suspected terrorists were seized and subjected to torture. Understandably, the U.S. wants to question Al Liby about Al Qaeda activities in North Africa. But it needs to promptly bring him to the U.S. and afford him the protections of criminal law. The Pentagon said he was “currently lawfully detained by the U.S. military in a secure location outside of Libya.” (The New York Times reported he was being held on a U.S. Navy ship in the Mediterranean.)

To his credit, President Obama has prohibited the use of “enhanced interrogation” methods such as waterboarding — i.e., torture — that were employed in now-closed secret Central Intelligence Agency prisons overseas. But suspicions linger about whether this country is abiding by international human rights standards.

For instance, although the administration has expressed a preference for trying prominent terrorism suspects in civilian court, it has put some suspects on trial before military commissions and claimed the right to hold dozens of other detainees indefinitely without trial. (In May, Obama said the status of those prisoners could be resolved “consistent with our commitment to the rule of law,” but no such solution has been announced.) In another troubling development, the U.S. has delayed informing some suspected terrorists — including accused Boston Marathon bomber Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, a U.S. citizen — of their rights under an elastic interpretation of the “public safety exception” to the Miranda rule.

In fairness to the administration, the acts allegedly committed by Al Liby are both violations of U.S. criminal law and part of an international campaign against American interests that many see as a war. (A State Department spokeswoman said Monday that Al Liby’s detention was justified by the Authorization for Use of Military Force passed by Congress after 9/11.) But in defending Al Liby’s capture, Secretary of State John F. Kerry indicated that the administration’s primary goal was to “hold those accountable who conduct acts of terror.” If that’s the case, the sooner he is transferred to the criminal justice system, the better.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.