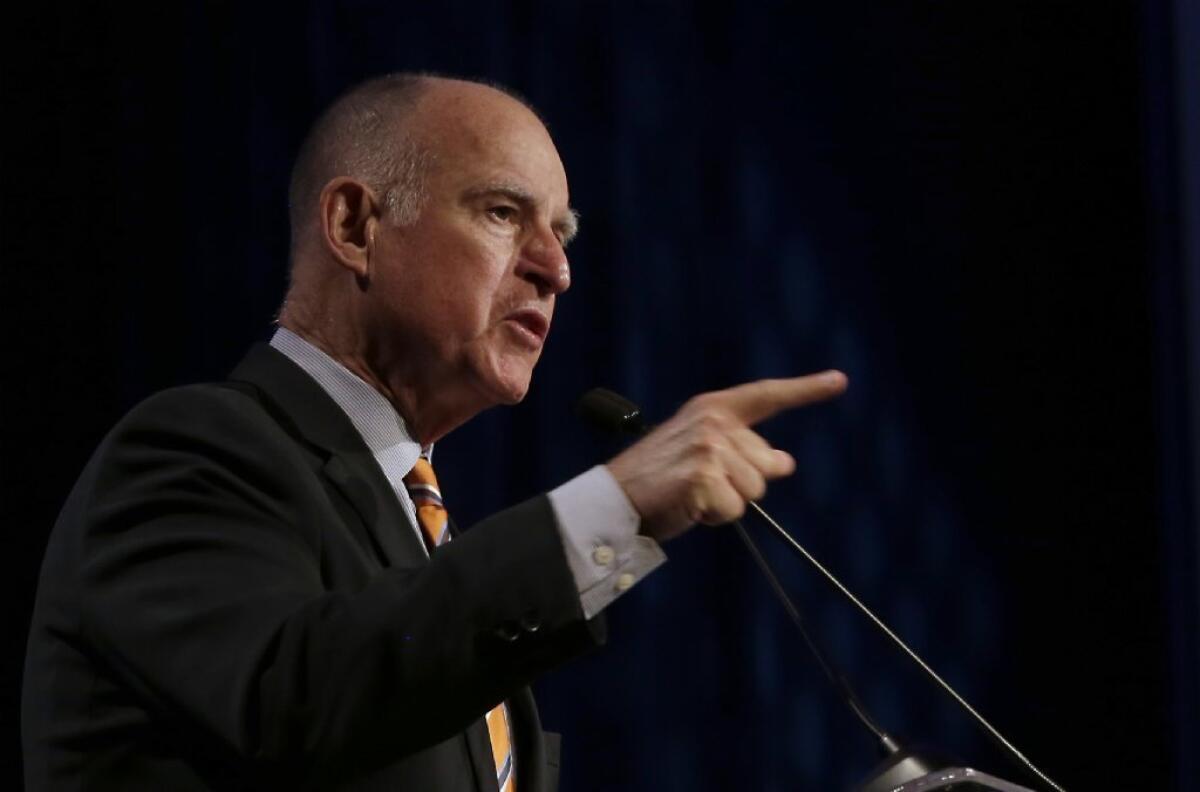

Endorsement: Jerry Brown for governor

Jerry Brown returned to the governor’s office in 2010 after the state had bottomed out and a cautious economic recovery was underway. At the same time, voters eased his job considerably by throwing out a crippling Depression-era constitutional provision that required a two-thirds legislative vote to adopt a budget. Pundits soon stopped calling California a “failed state” and ended their ridiculous comparisons with Greece. Now, many are going overboard the other way, calling the state a model or even a miracle. Overboard or not, though, Californians are certainly better off in 2014 than they were four years ago.

So was Brown merely lucky, showing up just in time to reap the benefit of the economic turnaround and of various voting and budget reforms? Or is he really so talented, so seasoned and just so — well, so Jerry Brown — that he deserves credit for getting California off the rocks?

It’s a little bit of the former, but it’s pretty clear that it’s also the latter, enough so that the choice for governor in this year’s election is easy. The Times recommends that voters keep Brown in office. The third term was a charm. Brown should have a fourth.

The call for Brown’s reelection necessarily comes with a reminder that the state budget’s (seemingly) sudden return to fiscal sanity is largely a result of yet another voter decision: to temporarily boost their sales and income taxes, with an emphasis on the word “temporarily.” One of the increases is due to end midway through what would be a fourth Brown term, the other at the end of it.

But even though voters deserve credit for Proposition 30, so does Brown — for pressing for it, for recognizing that the infusion of revenue was a prerequisite to the state’s recovery, and for making masterful moves on the political chessboard, tactically absorbing one potentially competing measure and completely rolling over another. Brown’s 2010 campaign promise not to increase taxes without a popular vote seemed at the time to tie his hands unnecessarily, and this page criticized him for it — but with the advantage of hindsight, knowing that the vote was successful, we must acknowledge that the state is better off for having voter buy-in.

This page was, and still is, unhappy with Brown for his battles with federal judges over orders to reduce the state’s prison population long after he had run out of legal and moral grounds for delay. But we likewise must acknowledge that California appears to be inching forward on overdue measures to direct more resources to rehabilitation and reentry services. The state should remain wary of the governor’s continuing enthusiasm for sending some prisoners out of state, but the prison population is dropping and the Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation has begun putting in place some inmate services.

Prison population reductions began with Brown’s public safety realignment program, begun in 2011, and although that program’s transfer of responsibility for many felons and parolees from state to county governments happened too quickly to work out all the kinks beforehand, Brown wisely saw that the move had been pondered and debated for decades without action. He took action.

In fact, for a politician so noted for his cerebral approach to problems, Brown deserves credit for action during his third term. In many ways he out-Schwarzeneggered Arnold Schwarzenegger. Public safety realignment was part of the Schwarzenegger agenda, as were temporary tax increases, a comprehensive program to preserve the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta and rationalize water policy, high-speed rail, a stronger budget reserve — all programs that Brown’s predecessor shaped but in the end couldn’t move. Brown is moving them.

He has also simplified and refocused the state’s school funding formula to make it fairer and to direct resources to students who need it most: children in foster care or in poverty, or those who are still learning English.

To be fair and to bring the story full circle, many of Brown’s accomplishments had their origins in Brown’s administrations in the 1970s and early ‘80s. For example, the school funding reform is an attempt to correct allocations set at the time Proposition 13 was adopted. Californians who turned to a young Jerry Brown 40 years ago because he was something new have turned to him again because he is something tried and true.

In some ways Brown has also out-Republicaned California’s Republicans by holding firm to the fiscal prudence that once was the chief calling card of the state’s GOP. Some legislative Democrats have rebelled; most have followed Brown as he has held the line on spending and pushed for a responsible rainy-day fund.

In earlier years, Brown’s Republican opponents would have faced off in a party primary, allowing them to test their philosophies and their voter appeal. It would have made an interesting race for the Republican nomination — between Neel Kashkari, a former assistant secretary of the Treasury and director of the U.S. government’s response to the banking crisis of 2007-08; and Assemblyman Tim Donnelly of Twin Peaks, founder of the Minuteman Party in California.

With the open primary, though, Kashkari and Donnelly are thrown into the mix with Brown and an assortment of other candidates, and some independent voters who might have shown interest in Kashkari as the more moderate of the top two Republican challengers could very well opt for Brown as the chief governmental mechanic most likely to keep California’s gears turning for the next four years.

It would be the right decision. Brown and California have a long, odd but somehow productive relationship, and it seems wise to keep it going for one more round.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.