Lawyers, songs and money

Send us your thoughts at opinionla@latimes.com.

Online music firms scored three victories last week at the expense of record labels, songwriters and/or performers. In the long run, however, those victories could end up helping everyone in the music business.

On Friday, a federal jury in Manhattan ruled in Yahoo’s favor in a long-running dispute with BMG (now combined with Sony Music in Sony BMG) over royalties. On Thursday, two members of Congress introduced a bill to cancel a looming increase in royalty rates for online radio stations, proposing instead to reduce the rates many webcasters pay. And on Wednesday, a federal judge in White Plains, NY, limited the royalties that songwriters could collect from online music services.

How much these developments alter the prospects for online music remains to be seen, and it’s worth noting the world of difference between introducing a bill and getting one signed into law. At the very least, though, the court rulings provide some clarity for companies trying to persuade consumers to pay for music online, rather than helping themselves to the many free sources of illegal downloads.

The Yahoo-BMG tiff grew out of a festering dispute between record labels and music services over personalization. Many online radio outlets embraced personalization because it made their playlists more compelling in a way that over-the-air stations couldn’t match. But label executives worried that tailoring webcasts to individual listeners would undermine CD sales.

The labels won vague limits on personalization as part of the compromise embodied in the 1998 Digital Millennium Copyright Act. The law said webcasters could automatically receive a license to play any songs they wished, provided that they complied with numerous restrictions on their playlists. The law also limited the license to stations that weren’t “interactive,” meaning that they didn’t provide specific songs on demand or “a program specially created for the recipient.”

In the years that followed, the labels tussled with several online radio services over the line between interactive and non-interactive. The apex of the battle came in 2001, when four of the major record companies sued Launch, a service that let users create customized stations by providing feedback about songs and artists as they played; Launch countersued. The labels alleged that Launch, which was purchased by Yahoo a few weeks later, offered interactive stations without a license. Launch pared back some of its features, and it reached deals with three of the four record companiesalmost certainly for interactive licenses involving higher royalties than the basic webcasting license, although no terms were disclosed. But it couldn’t reach a deal with BMG, and the case finally went to trial April 16.

It took the jury little more than an hour to reject BMG’s claim. Although the case applied only to Yahoo, the swiftness of the decision sent a clear message in favor of the kind of personalization that Launch provides. And despite the industry’s protests, personalized stations are better for labels and artists than generic ones. The tailoring of playlists means that performers and recordings will be heard by the people most likely to enjoy them. And because the stations don’t play music on request, they’re more likely to stoke demand than slake it.

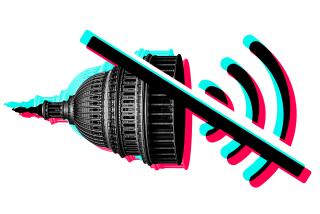

A bigger challenge for personalized radio, though, is the Copyright Royalty Board’s ruling last month to impose higher royalties and new minimum fees on webcasters. Companies that offer customized stations tend to do so by the hundreds. The new rates set by the Royalty Board, which are scheduled to take effect May 15, would require online broadcasters to pay a minimum annual fee of $500 per station, which is more than many webcasters could hope to raise in advertising.

The bill introduced by Reps. Jay Inslee (D-Wash.) and Don Manzullo (R-Ill.) would set the annual minimum at $500 per company. And instead of raising rates sharply, as the Royalty Board proposed, it would cut them by more than two thirds pending a new round of negotiations.

The Royalty Board and the Inslee-Manzullo bill suffer from the same problem: they apply the same rates to webcasting businesses regardless of their size. As a result, critics on both sides can say, with a certain amount of righteousness, that the other is not being fair. On one side, online radio advocates complain that the Royalty Board’s decision would force many webcasters to shut down, even though it wouldn’t be too much of a strain to large commercial outlets with hefty advertising revenues. On the other, SoundExchange (a royalty collection agency for labels and performers) blasts the bill as a give-away to greedy “mega-corporations,” such as Clear Channel and Microsoft.

The rhetorical duel is likely to intensify as May 15 approaches. Chances are slim that Congress will act before the new royalty rates kick in, but the bill should give webcasters some leverage as they try to negotiate discounts with SoundExchange. Given how limited playlists have become for over-the-air stations, it’s in the interest of labels and artists to keep as many online radio outlets in service as possible. They can’t be blamed for wanting the Clear Channels and Microsofts of the world to cough up a bigger piece of their advertising revenue, but they need to be a lot more realistic about what smaller webcasters and non-commercial stations can generate.

Last week’s other development came in a legal dispute among three companies offering subscription music servicesRealNetworks, AOL and Yahooand ASCAP, which collects royalties for songwriters when their songs are performed publicly. ASCAP, BMI and SESAC all collect “performance” royalties for songwriters from radio stations, bars and other venues, while the Harry Fox Agency collects “mechanical” royalties for them from record companies when their songs are pressed onto CDs. ASCAP had sought royalties from the subscription services not just on songs played from an online jukeboxwhich are indisputably “performances”but also on digital music files that subscribers downloaded to their computers. RealNetworks, AOL and Yahoo argued that ASCAP was seeking a “double-dip” for songwriters, who already collected royalties on downloads through the Fox agency. The judge agreed, ruling that there was no “performance” in a download.

The result may seem like a blow to songwriters, but it’s the only decision that makes sense. The problem facing songwriters isn’t that they’re getting paid too little for legal downloads. It’s that they’re not getting paid for illegal ones. Artificially driving up the cost of subscription services won’t help them draw consumers away from file-sharing networks and other sources of bootlegged tunes. That’s the challenge everyone in the music business faces, and they’re all ultimately on the same side.

Jon Healey is a Times editorial writer; he runs the BitPlayer blog .

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.