An activist in transition

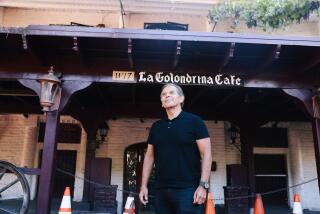

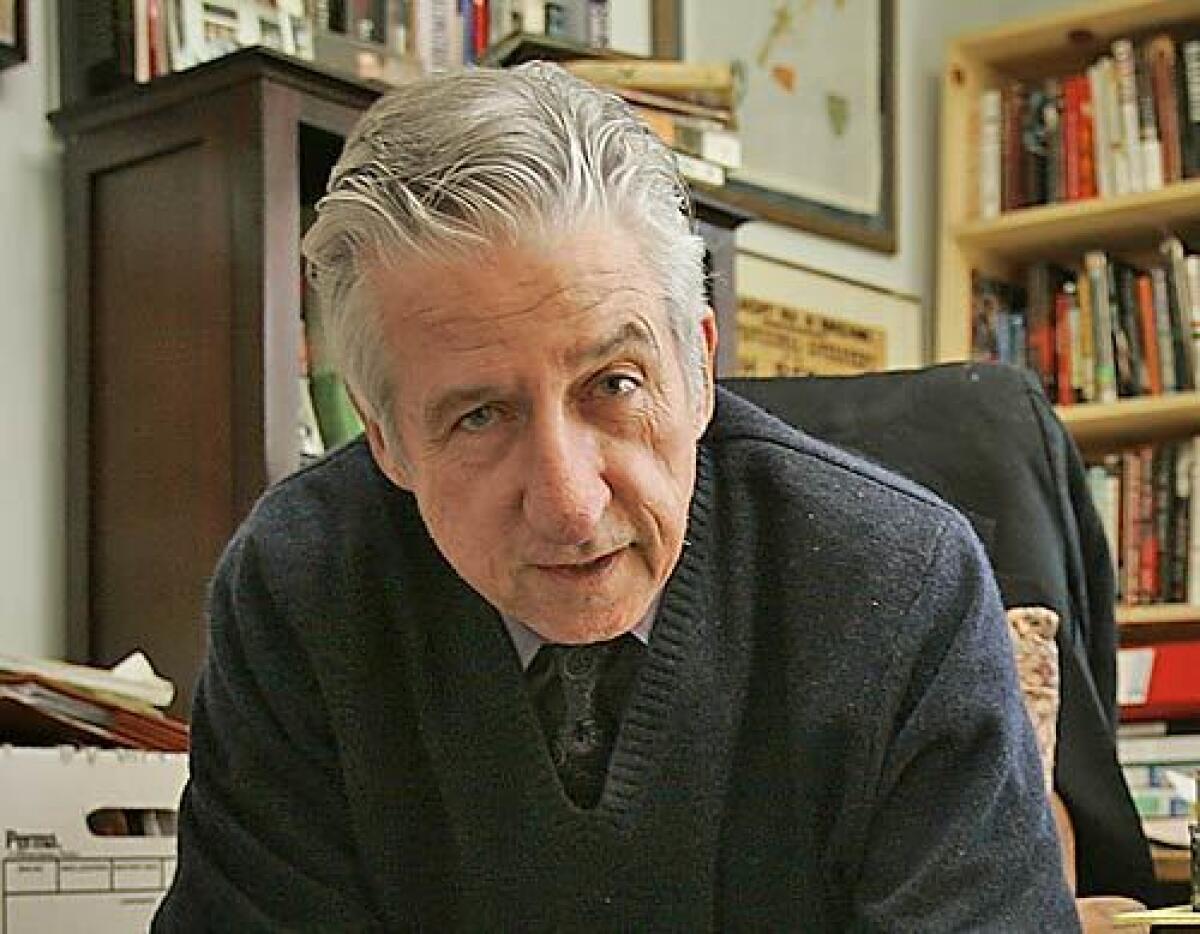

TOM HAYDEN — co-founder of Students for a Democratic Society, member of the Chicago Seven and avatar of protest and activism, a man who visited the enemy in North Vietnam during America’s war there, one whose break with his father caused them not to speak for 16 years — is suddenly the bearer of a light spirit.

Hayden, who had a heart attack a few years back, still writes and lectures, and still observes the workings of the political class. But these days, he closes up shop in time to make it to his 7-year-old son’s soccer games.

Tom Hayden, America’s emblematic youthful activist, is 67.

He wears his new disposition well. Once prone to prickliness, Hayden now exudes a gentle, mischievous sense of humor; he allows himself to think out loud, to glide from one topic to the next without fear of political consequences. In place of the hard glare that longtime acquaintances know all too well, Hayden’s signature has become the twinkling eye, the sly grin and — marvel of marvels — the giggle.

“I think there’s another act, a transition to seeing new leadership come along, taking care of your family, your kids, figuring out what it all meant, writing your memoirs, passing along your knowledge,” Hayden said, sitting in his Culver City office, surrounded by a jumble of art and memorabilia, a SpongeBob SquarePants toy and hundreds of well-worn books. “The idea of being a researcher, a writer and a teacher has a lot of attraction to me.”

In the middle of the antiwar movement, a close friend of Hayden once questioned whether he was capable of emotion. Now, his eyes water as he considers his consequential life: “I just try to reflect on whether I’ve done the best with what I’ve been dealt.”

The result: A recent conversation with The Times, intended as a discussion of urban poverty and street gangs, instead mushroomed into an elaborate, meandering, literate and cheerful reflection on Los Angeles history, race relations, protest, the legacy of the 1960s, his time as a member of the Legislature, the performance of Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa — and the weather.

Hayden’s interests have always been eclectic. Few authors can claim to have written books on Vietnam, Irish history and the environmental movement (not to mention the Port Huron Statement, the classic New Left manifesto of 1962). But some of his most resourceful journalism has been on the topic of gangs. “Street Wars,” first published in 2004, was built on Hayden’s extensive interviews — in Los Angeles but also throughout Latin America — with gang members, gang experts, law enforcement officials and political leaders.

In it, Hayden argued for a “New Deal” approach to gangs, the construction of a network of social service intervention programs intended to lure gang members into productive society. “Homies are not demons,” Hayden wrote, “but complex human beings capable of changing for the better.”

Since its publication, Hayden has watched a former legislative colleague and fellow liberal, Villaraigosa, be elected mayor of Los Angeles, a position that Hayden unsuccessfully sought in 1997. But Villaraigosa has not followed Hayden’s recommendations on gangs, and Hayden is increasingly uneasy with the mayor’s approach.

Villaraigosa has decried a recent spate of gang violence with regular news conferences, announcements of most-wanted lists and promises of stepped-up police response. Some have cheered Villaraigosa’s resolve, although others suggest that his hyperbole is intended to distract from his failed efforts to take over Los Angeles schools. Still another group, including Hayden, cautions that the mayor is risking betrayal of his core principles in order to secure political advantage.

“I don’t think very highly of it,” Hayden said of Villaraigosa’s proclamations. “I think he knows better. I’d like to believe he knows better. He’s pandering to fear and to the law enforcement lobby.”

Hayden does not dispute that violent gang members need to be arrested and incarcerated, but he argues that a policy that relies too heavily on police and enforcement — at the expense of intervention — is doomed to failure. Instead, he touts the need for creating and expanding thoughtful programs, with jobs and opportunity serving as lures to draw gang members away from their destructive affiliations.

Hayden’s proposal: “Just as we flood certain areas with police officers, we’re going to flood the same areas with jobs and social workers. What you’re trying to do is create cease-fire efforts. You’re going to develop case profiles of individuals in terms of job readiness, educational readiness, substance-abuse efforts. You’re going to have a huge rehabilitation program.”

Such programs are not impossible to create, Hayden argued; indeed, they exist to some degree in San Francisco, where Hayden credits those ideas with helping to contain gang violence. Moreover, Hayden, no stranger to politics, emphasizes that those ideas are within Villaraigosa’s reach.

“He could do all those things,” Hayden said. “He wouldn’t sound soft. It would actually lessen violence. He’d get wide support.”

Why, Hayden wondered aloud, does Villaraigosa not embrace that vision for tackling gang violence? “It could be that he’s preparing his run for governor,” said Hayden, who sought that office too, and knows the pressure on a statewide candidate to be tough on crime.

For Hayden, the city’s recent surge in attention to gang violence is just the latest in a string of dishonest attempts to grapple with a problem that has claimed thousands of lives. In the aftermath of the 1992 riots, Los Angeles embarked on a much-extolled urban investment effort, called Rebuild L.A. Implicit in that campaign, Hayden says, was the idea that gang members would renounce violence and that the public and private sectors would reward that move with investment and jobs.

Peter Ueberroth, who had previously made the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics a financial success, spearheaded that campaign. Although gang violence fell sharply, the rebuilding effort fell woefully short of its promises.

“That’s when I snapped,” Hayden said. “There was no soul-searching. There was a huge reduction in drive-by shootings. The truce in Watts was actually working. But there was no peace dividend. There were no investments in the riot area and no new jobs.”

The rise of gangs in Los Angeles, where more gang members are thought to live than anywhere else in America, has taken place against the backdrop of this city’s evolving ethnic politics. When Hayden first came to the city, its defining racial alliance was in black and white. Mayor Tom Bradley forged his famous coalition, in which Westside liberals, especially Jews, joined forces with the city’s black population to elect their mayor time and time again.

Today, African American political clout is declining, and Los Angeles is defined by the geometrically advancing influence of Latinos, particularly Mexican Americans. Hayden happily extols Los Angeles’ “re-integration with Mexico.”

“There’s a hybrid culture taking place here,” he said. “The African American community and the Asian communities combine to produce a majority mosaic of color with the Mexican and Central Americans.” Of those, however, some are ascendant and some are not: “The blacks won’t say this, but they’re on the decline in terms of political clout. They see it receding as the Bradley era has almost faded away. People don’t even remember it.”

L.A. is becoming a genuinely Mexican American city, one without much precedent but one that Hayden welcomes. He is fascinated by the political superstructure that Villaraigosa and allies such as Assembly Speaker Fabian Nuñez are erecting — “It’s all for seizing and holding power,” Hayden observed, more wistfully than resentfully. Of the hackneyed observation that Latino participation in Los Angeles politics is a “sleeping giant,” he laughed and noted: “I think those days are over.”

Once an activist, then an elected official, Hayden has softened into something else: a public intellectual. And in that capacity, he has contemplated the question of why Los Angeles so often seems to struggle with twin demons of hubris and insecurity. The answer, he has concluded, is Hollywood, specifically its glorification of celebrity over intellect.

That even plays out in gang circles, he noted, where young bangers are infatuated by Al Pacino’s portrayal of a cocaine baron in “Scarface.”

“They love his scorn of big-shot hypocrites,” Hayden noted.

Trashing Hollywood’s influence is a big pill for Hayden to swallow. He was, after all, married to actress Jane Fonda for more than a decade, and now is married to Barbara Williams, a singer, actress and screenwriter. And Hayden himself is something of a celebrity, albeit of the political variety.

Still, he has spent a life rooting out the negative influences of big business and cultural oppressiveness. He’s not about to stop now.

“Entertainment as a business reinforces celebrity,” he said. “Hollywood has sucked all of the intellectual talent into advertising and mediocre films.”

Why does this happen in Los Angeles? Why is this city the locus of gangs and the center of celebrity? Why are both the Los Angeles Police Department and the Metropolitan Transportation Authority under federal court orders? Why is ineptitude so often tolerated here?

Hayden hesitated, then admitted that he has a unified theory of sorts, not one that explains everything but one that goes part way: It’s the weather.

“People put up with more here,” he offered. “So what if the city is dysfunctional? So what if the city has gangs? We’re comparing it to Buffalo, where we came from; Detroit, where we came from. Cities with weather are much more concerned about city services.”

Montreal, he noted, is cold and well-run. It has to work at its quality of life. Los Angeles, by contrast, is forgiving. It allows failure, it is elastic, permissive. Warm.

That is the kind of observation that Hayden once would have offered with bitterness. Now, he serves it up with a touch of wonder. Leaving his office and walking down a street on a cool spring morning, he waved goodbye to his visitor and then turned to head back, to gather his things and head off to his son’s soccer game. A man in a T-shirt recognized him and called out hello.

“Beautiful day,” Hayden replied.

--

jim.newton@latimes.com

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.