Op-Ed: My difficult mother: She made me hang on all the harder

“Oh, Michelle.”

Since my mother died 26 years ago, nobody has said those two words with quite the same resonant blend of sorrow and disappointment.

My mother was intelligent, talented, highly complex and energetic. Always tanned, she wore big glasses, and her hair was a mink-brown cap.

During her childhood, her farmer father woke her every morning at 5 to practice piano in the basement before school, and at 16 she went to the Oberlin Conservatory. Trained to perform, she was hobbled by terrible stage fright. Once she graduated, she never practiced regularly again, and the grand piano in our living room sometimes went untouched for years.

She still loved Schumann and Brahms. Symphonies, played loud, relaxed her. As did mystery novels. Bourbon. Later on, bridge.

Parents are not supposed to have favorites, but sometimes members of a family naturally gravitate to each other. My father and my sister did, and so did my mother and I.

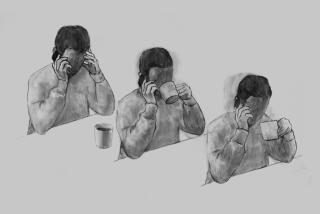

Our relationship was not easy. A diabetic with an erratically functioning pancreas, my mother’s moods were operatic; she took us all on wild emotional rides. She drank too much (not a good mix with zigzagging blood sugar), and she never got a handle on her anxiety and anger, or on any other emotion. As a parent, she was strict, short-tempered and easily bored; also a great yeller, slapper, spanker and upper-arm grabber. There was never any reasoning with her; in her world, children had no rights.

I held on all the harder.

Affection embarrassed her; if I hugged her or snuggled up, she’d say, “What brought this on?” Then she’d ask me to scratch her back.

And sometimes she would call out sternly from the other room, “Michelle, Michelle! Get in here.” In fear, not knowing what I’d done wrong now, I’d go to her.

She’d be at the window. “Look! Look at that sunset!”

I was connected to her as by a fine, live wire. If my father raised his voice at her, I burst into tears. I couldn’t bear to have her rebuked. I knew the pain of being yelled at — she’d yelled at me plenty — and I couldn’t stand for her to feel it, because then she’d know how wildly mean she was to her own daughters. I wasn’t sure she could survive such self-knowledge.

My mother went back to school for a teaching certificate when I was 7. Teaching elementary school made her both happier and more stressed. Curiously, even as she became known for her innovations in the classroom, my mother took no interest in our schoolwork (except our grades). Decades later, she said she’d never pushed us in school because of how she’d been forced to practice every morning in the dark.

She pushed on other things. She had problems with my friends, my clothes, but most of all, my hair. “Oh, Michelle. I wish you’d do something with your hair.” Fine, stringy, incapable of holding a curl, I yearned to wear it long. She championed the pixie cut. And when she was certain that I was attracting the wrong friends in the 10th grade, she took me to the beauty parlor and had it cut even shorter than a pixie.

Our best times were Saturday mornings, when we shopped, hitting the produce market, the butcher, the little Armenian store, the Italian deli. We shared an interest in food and cooking, which were about the only things we could discuss without tussling.

We had one great year when things were balanced and sweet between us, and something like mutual respect took hold. During my senior year in high school, I decided to cook dinner every night. For the first time, she had time to unwind after work. That, and gratitude, softened her. She became kinder, even reasonable. She allowed me greater freedoms, more time with my friends.

When I went away to college, we lost this ease; disappointment and disapproval flooded back. Once, I stayed away for more than a year.

After graduate school, as I struggled to publish, she grew impatient with me and, on the sly, sent out my stories, landing me my first agent. Once, when I was visiting her, an editor phoned; she said he couldn’t talk to me until he paid me for my last piece.

She disapproved of all my boyfriends, though I like to think she would approve of my husband, Jim, for being smart, sweet and, like her, Jewish.

However volatile her emotions were, I am grateful daily for the values she instilled. She read voraciously, she insisted (with my dad) that we take summer-long driving trips: across the country, to Guatemala (twice), to Alaska via the Alcan highway (twice). We went to art movies, plays, museums, concerts. She loved scenery, fishing, her mountain cabin. And shoes.

She died young, at 62, after a long, slow bout with cancer. I was 34 and just beginning a self-supporting writing life.

Once she died, I thought fondly of her, mostly. I could cut her some slack. We’d liked each other. We were fundamentally and profoundly attached.

Bits of her are scattered throughout my novels, but she’s most present in my latest, “Off Course,” as a mother watching helplessly as her daughter veers into trouble. In the writing, I was struck for the first time just how profoundly my mother had wanted to help when I was making my own wrong turns at that age. For the book, I borrowed her paltry if well-meaning attempts to steer me straight, voicing her disapproval even as she brought me Price Club bargains, sneaked me checks, and once even confided her own young, secret and illicit struggles with love.

As I age, I experience anxiety, waves of indecision and jangly dread. I hear her tremor in my voice. I have that urge to make my discomfort someone else’s fault or problem. I try to resist — something she rarely did — though I’m not always successful. Retrospectively, my heart goes out to her. She never found any distance, any respite from the tumult of self.

She’s been gone 26 years now. I think of her in complicated chords of love and pain, gratitude and mounting compassion, many times every single day.

Novelist Michelle Huneven is the author, most recently, of “Off Course.”

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.