Op-Ed: How the Danes, and a German turncoat, pulled off a World War II miracle

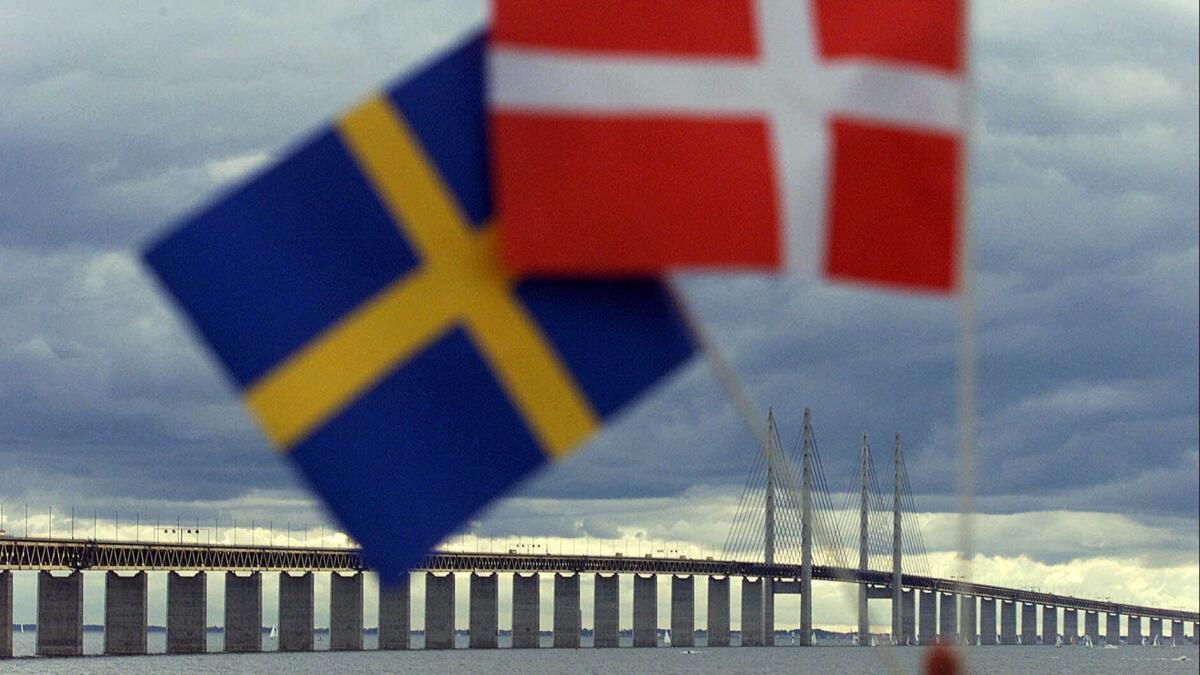

Seventy-five years ago, a legendary act of heroism unfolded across the Oresund, the narrow body of water separating Denmark and Sweden. Over a fortnight in October 1943, the Danes defied their Nazi occupiers and smuggled out to safety more than 7,200 of their Jewish neighbors, making trip after trip across the waterway.

Almost unknown, however, is the story of Georg Ferdinand Duckwitz, a German bureaucrat in Copenhagen who risked his life to warn the Danish Jews of the impending roundup and made crucial arrangements to ensure their escape. Were it not for Duckwitz, who would later become West Germany’s ambassador to Denmark, the miracle on the Oresund would not have been possible.

An economist and lawyer from an affluent Bremen family, Duckwitz first came to Denmark as a 25-year-old coffee trader and fell in love with his “chosen fatherland,” as he called it. The Nazis tapped his knowledge of Scandinavian shipping, and he was in Copenhagen, working for them, when German troops crossed the border in April 1940.

To the Nazis, Danes were Aryans, and their nation’s location was of such strategic import that Berlin decided to rule them with a light touch. The Danish government and King Christian X remained in place, and even the military and police were left more or less intact. As a condition of their cooperation, the Danes demanded the Germans leave their small Jewish community, which dated back to 1622, unharmed. The well-known story of King Christian wearing a yellow Star of David in solidarity with his subjects is apocryphal, because Christian did not permit such persecution to begin with.

Georg Duckwitz, who put his career and even his life on the line, offers an object lesson on how one person can save thousands.

Despite Denmark’s outward calm, resentment of the Germans simmered. The Danes conducted themselves with cold politeness. This worked for two years, until Christian responded to a long birthday greeting from Adolf Hitler with a terse five words — “My utmost thanks, Christian Rex.” The Fuhrer was enraged. In retaliation, he appointed SS Gen. Werner Best, known from his time in France as the Bloodhound of Paris, to take charge in Copenhagen.

The arrival of Best was positive for Duckwitz’s standing. He was a halfhearted Nazi, but Best needed his knowledge and contacts among the Danes, especially once the local situation deteriorated.

After Germany’s defeat at Stalingrad in February 1943, the Danish resistance grew bolder, engaging in daring acts of sabotage and encouraging mass strikes. In March, in a nearly unanimous vote, an anti-fascist coalition won the Danish parliamentary election. In August, after the bombing of a German barracks, martial law was declared.

Best now moved against the Jews. On Sept. 8, he cabled Berlin: The state of emergency provided an opportunity to apply the Final Solution to Denmark. Duckwitz tried to resign, but Best wouldn’t have it. Duckwitz then began a frenzied campaign to try to stop the deportation.

He first flew to Berlin in a fruitless attempt to intercept Best’s cable to Hitler. He was back in Copenhagen on Sept. 17 when Hitler approved Best’s plan. German police began arriving. They broke into the Jewish Community Center and seized a list of Jews.

On Sept. 19, Duckwitz learned from Best that the operation was imminent. He wrote in his diary, “Now I know what I have to do.” When he was told by a fellow sympathetic official that he would risk Gestapo wrath if he were caught trying to countermand Hitler, Duckwitz responded he would do whatever it took to stop the deportation.

The next day, Duckwitz contacted two Swedish diplomats and traveled to Stockholm where he met with Prime Minister Albin Hansson, who agreed to propose to the Germans that his neutral nation would intern the Danish Jews. The Nazis didn’t even bother to respond.

On Sept. 28, Best received the go-ahead to launch the roundup, planned for Oct. 1, Rosh Hashana. Duckwitz immediately telephoned Danish political leaders. One of them later recalled that when they met, Duckwitz looked pale with shame and shock.

“Now the disaster is at hand,” Duckwitz said. Ships were waiting in the harbor to take the Jews to the Theresienstadt concentration camp. “Those of your poor Jewish countrymen who get caught by the Gestapo will [be] … transported to an unknown fate.”

Enter the Fray: First takes on the news of the minute from L.A. Times Opinion »

The Danes moved quickly, warning the leaders of the Jewish community. On Sept. 29, the chief rabbi of Copenhagen, Marcus Melchior, spoke in the synagogue: Go home now and hide, he said. That night, Duckwitz wrote about Germany’s tawdry enterprise: “They will not find many victims.” It was his 39th birthday.

Over the next few days, millions of Danes would shelter, protect and smuggle their Jewish neighbors to Sweden. They were delivered to the harbor in free taxis and hospital ambulances. Fishermen and ship captains made more than 700 trips across the Oresund. Duckwitz had tipped off his Swedish contacts, who were waiting to assist the refugees. And in a final critical action, he convinced German harbormasters he knew to ensure the coast guard sent out no patrols.

In the end, only 481 Danish Jews were arrested and taken to Theresienstadt. The Denmark authorities relentlessly inquired after them, sending food and medicine and demanding inspections. At war’s end, 99% of Danish Jews had survived. When they returned to their homes, they largely found them clean, plants watered and pets cared for, and their belongings in place.

Many ask themselves whether it is possible to stand up to pervasive evil. The Danes showed that when a nation — from the king to the taxi drivers and fishermen — decide they will not permit atrocities in their midst, even the Nazis could be hamstrung. And Georg Duckwitz, who put his career and even his life on the line, offers an object lesson on how one person can save thousands.

This week, we should remember — and honor — them all.

Richard Hurowitz is the publisher of the Octavian Report, a magazine about foreign policy, economics, culture and ideas.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinionand Facebook

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.