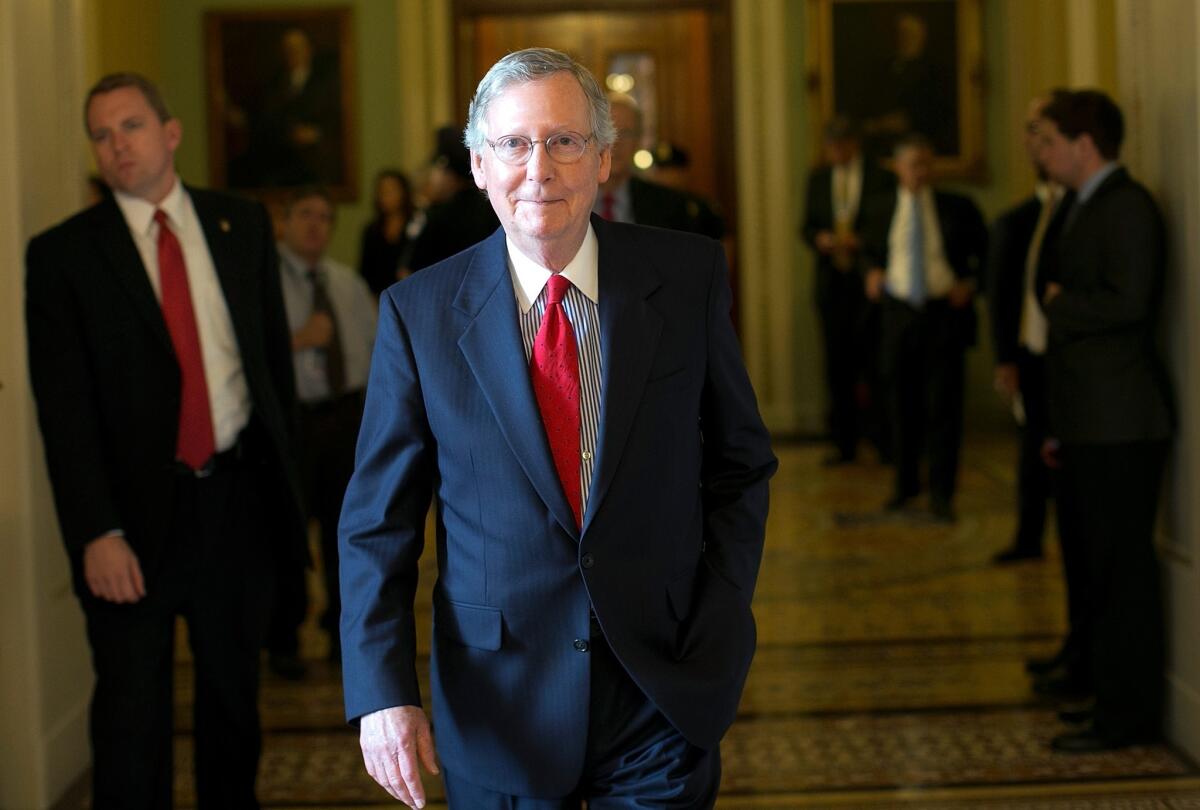

McConnell delivers; Boehner can’t

God bless Mitch McConnell.

The Senate Republican leader isn’t an especially lovable figure. Even many of his fellow conservatives are lukewarm about him.

He’s colorless and charisma-free. He’s a thoroughgoing partisan who has launched more filibusters than any Senate leader in history. He’s a relentless fan of unlimited campaign spending and a bitter opponent not just of Obamacare but of all things Obama. Asked in 2010 to describe his highest legislative goal, he said it was to make sure Barack Obama was a one-term president.

PHOTOS: Tea party backlash: Protest signs to cheer you up

But the wily Kentuckian is also an old-fashioned legislative strategist who can count votes, discern when his party is holding a losing hand and make the decision to cut a deal.

That’s what McConnell did this week when he sat down with his Democratic counterpart, the equally unlovable Harry Reid of Nevada, and struck a bargain to reopen the federal government and avert the danger of a default on the national debt.

“No one wants a default,” McConnell said. “So let’s put this hysterical talk of default behind us and instead start talking about finding solutions.”

McConnell took a distinct political risk in agreeing to extend the federal debt ceiling until February with almost no strings attached. The Senate Conservatives Fund, a fundraising group that backs primary challenges to Republicans it deems insufficiently hard-line, denounced him for “negotiating surrender.” (This column won’t do him much good either.)

But McConnell could read the polls. The longer the government shutdown continued and the closer the nation came to a politically induced financial crisis, the more the GOP was losing.

And McConnell, a ferocious enforcer of discipline, knew he could deliver most of his party’s votes. “There are few things more daunting in politics,” Sen. John McCain (R-Ariz.) once said, “than the determined opposition of Sen. McConnell.”

But whether a deal is on track by the time you read this column — something in no way certain as I write these words — doesn’t depend on McConnell alone. His counterpart on the other side of Capitol Hill has a tougher job.

House Speaker John A. Boehner (R-Ohio), who holds a safe seat and commands a 32-seat majority, can’t manage to work his will among the 232 Republicans who chose him as their leader.

On Tuesday, Boehner and his lieutenants tried to unveil a proposal of their own to end the budget standoff, one with tougher conditions than the bargain McConnell struck with Reid. The idea was to give the House a coherent position from which to negotiate with the Senate and to avoid being “jammed” to accept the McConnell-Reid deal as the Oct. 17 deadline for lifting the debt ceiling bore down.

In a basement conference room in the Capitol on Tuesday morning, House Republicans gathered, bowed their heads, and — in lieu of an opening prayer — sang three a cappella verses of “Amazing Grace.”

It went downhill from there. Tea party conservatives, who had caucused the night before at a Mexican restaurant called Tortilla Coast, complained that Boehner’s draft didn’t do enough to block Obama’s healthcare law. Fiscal conservatives balked at lifting the debt ceiling for as long as the four months proposed by the Senate.

Boehner warned his colleagues — as he has many times — that flirting with the debt ceiling was a bad idea. “The idea of default is wrong, and we shouldn’t get anywhere close to it,” he said. But after a day of backroom negotiations, the speaker withdrew his own draft proposal, leaving the House without any plan at all.

The difference between the two leaders isn’t merely a matter of talent or style. Because House members represent much smaller, often more homogenous constituencies, many of them see no reason to compromise. This week, for example, as polls showed the Republican Party plummeting in the eyes of voters, Rep. Jim Jordan (R-Ohio) dismissed the numbers, saying it was more important for conservatives to stick to their principles.

McConnell’s challenge is different: His mission is to make it possible for Republicans to win the six more seats they need to secure a majority in the Senate. That means fighting for conservative principles when he can, but not at the cost of diminishing the GOP’s appeal to centrist voters.

In the House, the roughly 35 Republicans who ally with the tea party make the difference between a majority and a minority for the GOP. In the Senate, McConnell has to contend with only three tea party renegades in his caucus of 48: Ted Cruz of Texas, Mike Lee of Utah and Rand Paul of Kentucky.

The difference mirrors the larger dilemma faced by the Republican Party nationwide: Should it focus on building a grass-roots movement of committed tea party conservatives, or seek to enlarge its coalition by welcoming more moderates and pragmatists?

The answer matters to McConnell in more ways than one. He faces a well-funded Tea Party opponent in Kentucky’s GOP primary next year. If he can survive that challenge and help six more Republicans win Senate seats, he might yet achieve his ambition of being sworn in as majority leader in 2015.

Twitter: @Doyle McManus

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.