Op-Ed: My teacher, the predator

A few months ago, I sat in a small gray conference room and listened as four middle-aged men read aloud from my high school diaries. They parsed each line, asking me to explain the technicalities of my teenage abbreviations and cadence, searching for evidence that I had — unknowingly — witnessed a crime.

Joseph Thomas Koetters was my English teacher at the Marlborough School in Los Angeles. In 2015, he was sentenced to a year in jail on charges that he engaged in sex acts with two underage girls in the early 2000s.

Although I was oblivious to my teacher’s predations, I knew one of the young women he targeted. Chelsea used to walk around with a half consumed iced mocha latte and a soccer bag slung over her shoulder. She explained our calculus homework to me so often that I saved her number as “Chelsea Math.” As I discovered years later, she found out she was pregnant in a Carl’s Jr. bathroom, and miscarried soon after.

Chelsea didn’t need to go through that. No one should have to go through that.

While some sexual violence is overt and obvious, a lot of what makes abuse possible happens in small, quiet, deceptive ways.

The lawyers reading from my diaries were taking my deposition for a civil suit against Marlborough. They were building a case that the school was negligent in identifying my teacher’s behavior and responsible for ignoring years of complaints that students had registered against him.

I attended Marlborough from 7th to 12th grade. I loved it. The sprawling, well-kept campus and time-honored rituals like pin ceremonies and senior class songs provided a refuge from the chaos of adolescence. I trusted Marlborough, my parents trusted Marlborough, and I trusted Koetters. He was a transgressive, effective teacher who challenged us to think outside the box and talked to us like the adults we thought we were. He led class discussions on books with complex adult themes like J.M. Coetzee’s “Disgrace,” in which a professor rapes a vulnerable young student. He listened carefully to our thoughts and opinions. My friends and I liked him so much that we referred to ourselves as the “KFC,” the Koetters Fan Club.

Koetters never touched me, but in the years since the case was made public, I have often thought that I should have noticed and done something to stop his abuse. As an adult reading back through my diaries, it is glaringly obvious that something was wrong.

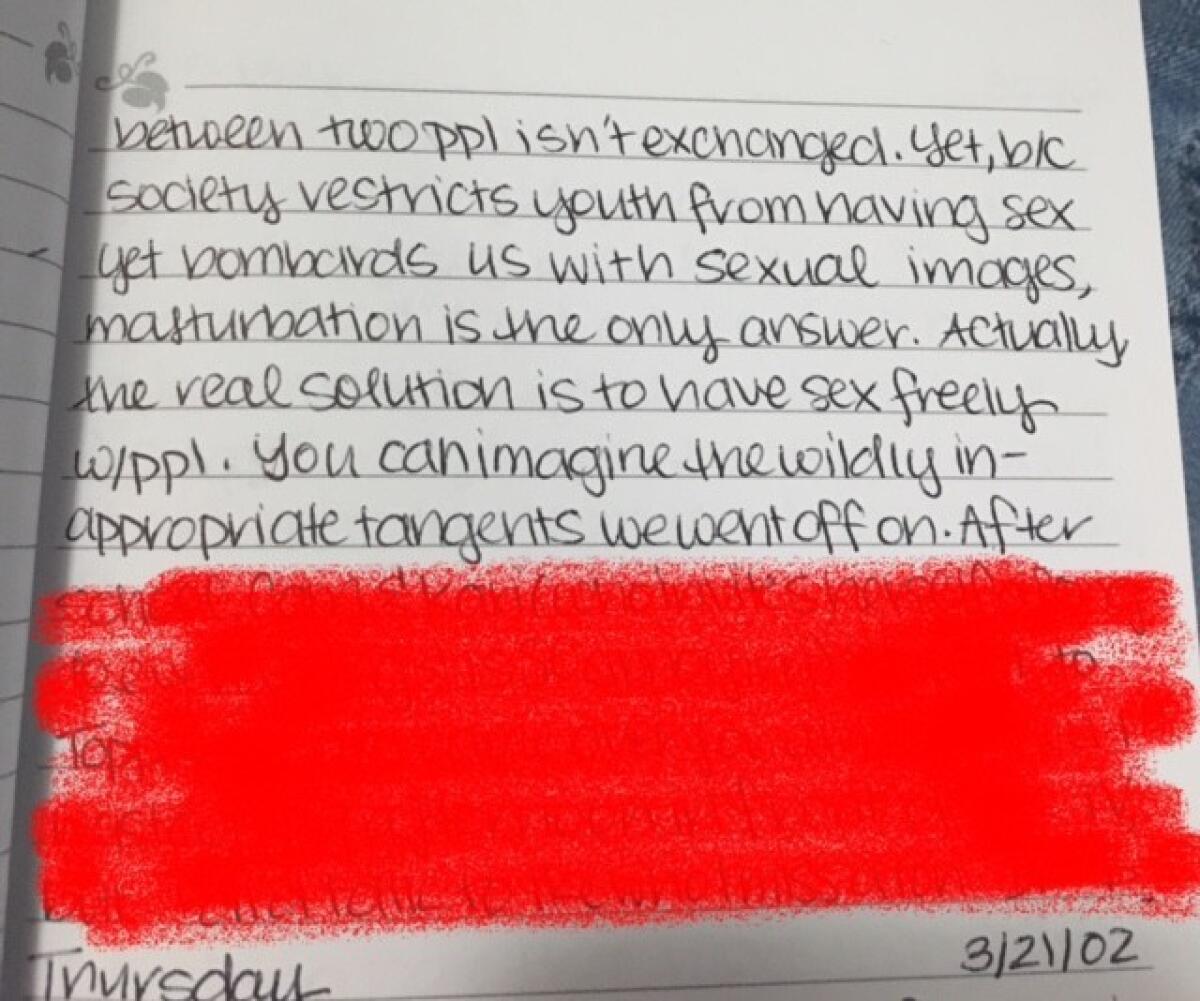

I once wrote: “Koetters told me I’m sexually repressed.” At the time, I wasn’t sure what that meant. I also wrote about the time our senior class read D.H. Lawrence’s short story “The Rocking Horse Winner.” I wrote down that Koetters told us young people are told not to have sex, and yet we’re bombarded with sexual imagery, leaving us with no option but masturbation. The real answer, he said, according to my notes, is to have sex freely and openly. I had never known adults who talked so overtly about sex. It felt grown-up, and a bit gross. In the discussion of the story, Koetters focused on the masturbatory elements and then asked one of my classmates, “So, how do you masturbate?”

I was a witness who did not see; I perceived my teacher’s behavior through a guileless lens. I remember hanging out in the halls with Koetters and a couple of other girls. I saw he had something on his neck. I asked if it was a hickey and he said, “No it’s a pimple. But you can suck on it if you want and get out the puss.” I remember giggling nervously in response. It struck me then as weird; it strikes me now as egregious. When I recounted this memory to the lawyers, they were visibly uncomfortable.

In hindsight, it seems that Koetters was carefully pushing at the edges of normal-seeming behavior to create an atmosphere in which his actions would go unseen and unreported. He preyed upon my innate teenage desire to break the rules, confirming what I already thought might be true, that the boundaries dictating appropriate behavior were arbitrary and false. At 16, I believed that I was hastening adulthood by accepting his radical seeming perspectives on sex and student-teacher dynamics.

For these reasons, I never saw him as a threat to me or my friends. I thought the men to fear were the ones I imagined skulking around the dark edges of my home at night, or the handsy boys who offered to drive me home after a school dance. My former teacher’s pattern of abuse is a reminder that while some sexual violence is overt and obvious, a lot of what makes abuse possible happens in small, quiet, deceptive ways.

Like many people who commit sex crimes, Koetters didn’t operate in a vacuum: Marlborough maintained an institutional culture that enabled him to abuse his power. As students, we were taught to question political and economic power, but we weren’t encouraged to understand or challenge abuses of power from within our own ranks.

The attorneys asked me again and again if I ever relayed Koetters’ sexual comments to a teacher or an administrator. “No,” I said, that would have been unthinkable. High school was a hierarchical microcosm in which the teacher’s authority was absolute. I was not aware of any secure channels to report abuse (though I understand they have since created these), and I doubt I would have reported him if I had.

It was a small school and a tightknit community. I always assumed that the administration knew how Koetters behaved. To an extent, that assumption was correct. Vanity Fair reported in 2015 that, after Chelsea and I graduated in 2002, Koetters harassed other teenage girls. Although some of them lodged official complaints, the school did not fire Koetters. In 2013, he left quietly and took a job at another expensive private school.

I don’t think the school was part of a nefarious plot. Why did they ignore Koetters’ behavior? Was it a combination of indifference, ambivalence, assumptions about teenage girls’ proclivity for drama, and fear of getting into a lawsuit? Regardless, by ignoring allegations from students over the years, the school sent a message to young women: sit down, shut up, and suffer male entitlement.

Institutions, companies and communities need to talk more explicitly about power, abuse and consent. Schools especially must not only protect girls and teach boys not to rape, but encourage everyone to speak openly about power dynamics, even if it implicates the institution itself. We need to show young people what wolves look like, and what kinds of clothes they wear. We need to explain the difference between transgression and crime, between sexual exploration and sexual abuse. We must teach young people to recognize environments that sanction abuse, and highlight safe channels of reporting. We must talk about how age, race, gender and ability affect power dynamics. We need to investigate allegations old and new. “Trust women” is a common refrain in the anti-sexual violence discourse, but it has to start with “trust girls.”

Chloe Safier is an independent consultant who works on global women’s rights and gender justice. She tweets at @chloelenas.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion or Facebook

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.