Op-Ed: To spur job creation, bring on supply-side economics

The Congressional Budget Office says unemployment won’t drop to 5.5% — the benchmark for “full employment” — until 2024. That implies a 15-year recovery from the Great Recession (which officially ended in June 2009, when the economy started growing again).

That projection seems at odds with recent labor market improvements. Employment has increased by 7 million since October 2009 and unemployment has fallen from 10% to 6.7%. But the population continues to grow, bringing more workers (including immigrants) into the labor market.

To bring the unemployment rate down further, job creation has to be faster than population growth. That’s just for starters. Then there are those 2.3 million workers who are sitting on the labor market sidelines because they are so discouraged by futile job-seeking that they are not actively looking for work (and not counted in official unemployment statistics), and an additional 7.2 million who are working part time while waiting for full-time employment. Those workers will trickle into the labor market as job prospects improve.

To get back to the 4.7% unemployment we had in 2007 requires nearly 300,000 new jobs every month. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, that has happened in only two of the last 62 months.

The current recovery is so much slower than earlier ones that it easily qualifies as America’s worst. In less than one out of 24 months have at least 300,000 jobs been created. In the recovery from the 1973-75 recession, 300,000-plus jobs were created in 14 months out of 24; for recovery from the 1981-82 recession, 13 out of 24 months; for the 1990-91 recession, nine of 24 months.

Moreover, in 1978 total U.S. employment was only 83 million people, compared with 137 million in 2014. So, creating 300,000 jobs per month was a much more extraordinary feat in that much smaller labor force. To match the job creation records of 1973-75 and 1981-82 would require job creation of 450,000 to 500,000 jobs per month in today’s labor market. That has happened only once in the last 62 months.

It took four years to restore full employment in the wake of the 1973-75 recession, 5 1/2 years after the 1981-82 recession and only 2 1/2 years after the short 1990-91 recession. The CBO says it will take a staggering 15 years to achieve in the current recovery.

What accounts for this abysmal track record and gloomy forecast? The 2009 American Recovery and Reinvestment Act and subsequent tax/spending initiatives add up to the largest fiscal stimulus in history. The same is true for monetary policy: The Fed drove interest rates down to near zero and has continued to pour reserves into the banking system. The end result has been the most aggressive use of fiscal and monetary policy tools in history. Yet job creation has been agonizingly slow.

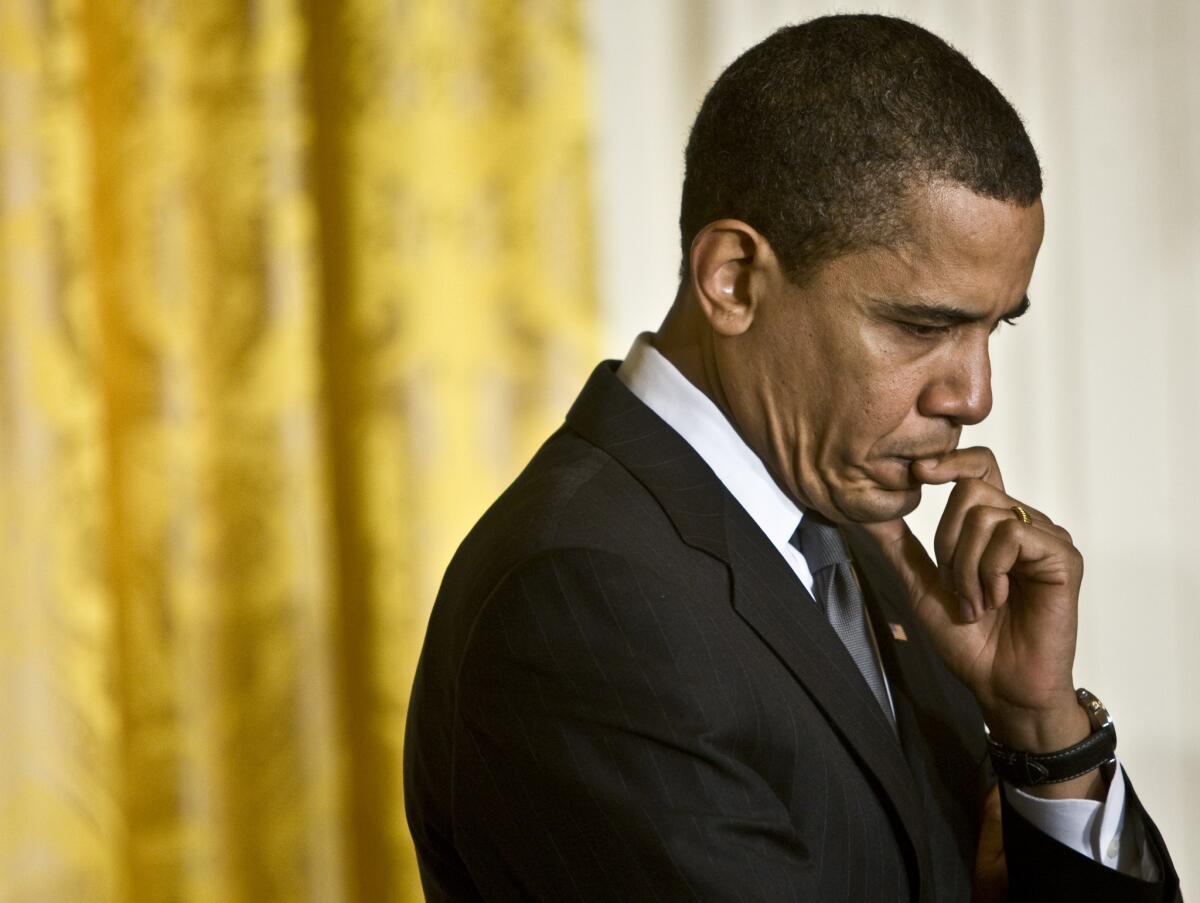

Why? The greatest failing of the Obama administration is its refusal to recognize, much less accommodate, supply-side determinants of job creation.

Supply-side policy focuses on the conditions that influence business creation, production and hiring decisions. What inspires or deters business start-ups? What motivates producers to increase output? Hire more workers? Invest in new machinery, buildings and technology? Demand for goods and services is a critical consideration in those decisions, but not the only one. Tax rates count, as do regulations on banking, production and payrolls. Ronald Reagan understood this well, heralding the heyday of supply-side economics with dramatic cuts in marginal tax rates for small businesses.

What this administration has instead given us are disincentives for business and job creation, such as the Dodd-Frank bank reforms, which have kept a stranglehold on bank loans for nearly five years. How else is one to explain the huge buildup of bank excess reserves in a growing economy? Any homeowner who has tried to refinance or buy a new home in recent years knows how odious and uncertain the process has become. Small businesses don’t stand a chance of getting loans in this uncertain and restrictive banking environment.

The 2010 Consumer Financial Protection Act exasperated the financing problems of small businesses, burying alternative financing sources in red tape. Then there’s the marquee Affordable Care Act, which has raised payroll costs and discourages the hiring of full-time employees. Now the White House wants to increase the minimum wage by 40%, an initiative that the CBO says would eliminate 500,000 jobs in its first two years.

The greatest obstacle to faster job creation is the continued unwillingness of the Obama administration to even recognize the possibility that its interventions might actually deter small-business creation and more hiring. It asserts that new banking regulations have made consumer access to loans easier and cheaper, that healthcare reforms will create jobs and save businesses money, that higher marginal tax rates don’t discourage work and investment, and that minimum-wage hikes don’t eliminate jobs.

So long as the White House continues to wear such ideological blinders, full employment will be elusive. However meritorious banking, healthcare, transportation and workplace reforms might be, we have to consider their unintended and largely negative consequences for job and business creation. To restore full employment in less than 15 years, we need more supply-side incentives, not more fiscal and monetary stimulus.

Brad Schiller is emeritus professor of economics at American University and the author of “The Economy Today.”

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.