Don’t let the killjoys kill football [Blowback]

- Share via

Bill Dwyre, who served as sports editor for the Los Angeles Times for a quarter of a century, wrote Tuesday that “the NFL deserves to go away, to be banished from our sight forever.”

When football’s natural amen corner raises pitchforks and torches against the NFL, the game is in more trouble than we know.

Dwyre’s piece is right about one thing: As much as he’d like the NFL to go away, the $10-billion behemoth is here to stay. But it’s worth remembering that the NFL doesn’t equal football. League Commissioner Roger Goodell’s revenues may be up, but sandlot and high school football participation is down.

ABOUT BLOWBACK: FAQs and submission policy

Football as a game that large numbers play rather than just watch faces an existential crisis. This fall’s casualties in the war on football are many.

The headmistress of the Lawrenceville School sacked America’s oldest football league last month. School administrators at the New Jersey prep school point to dangers such as head injuries as justification for the ban. The intramural league that kicked off 124 years ago reinvented itself in September as a flag football league. One senior lamented that “the oldest football league in the nation has been reduced to an elementary school gym class.”

In leafy Newton, Mass., flag football rather than tackle has drawn the ire of scolds. Newton South Principal Joel Stembridge cited safety, sexism and the exclusionary nature of the annual “powder-puff” game as reasons for unilaterally ending the all-girl Thanksgiving-eve tradition. “The game itself is dangerous,” Stembridge explained to parents, and it “does not include the whole school. It does not celebrate the diversity of the interests of our students.” He held that “in terms of gender politics,” the powder-puff game “perpetuates negative stereotypes about femininity and female athletes.”

Stembridge’s female students refused to call the principal’s paternalism progress. Hundreds of students initially protested the headmaster’s edict by wearing school colors, and then girls showed up en masse to school in funeral black. Lucy Holmes, a Newton South soccer player, told the Boston Globe, “Powder-puff is a celebration of women’s sports.”

There are generations of history between the Lawrenceville and Newton South traditions. In all that time, these rites of passage haven’t claimed any lives. Rather than turning out brain-damaged zombies, the schools’ alumni run the country.

The great paradox of the war on football is that it intensifies as the game’s casualties dissipate. Football hits killed an average of 14 players a year during the 1950s, 23 a season during the 1960s and 15 annually during the 1970s. Football collisions killed just two players, both adults, out of 4 million competitors last season. Safety improvements happily shift the conversation from fatalities to concussions, whose symptoms prove more fleeting than those unleashed by the grim reaper.

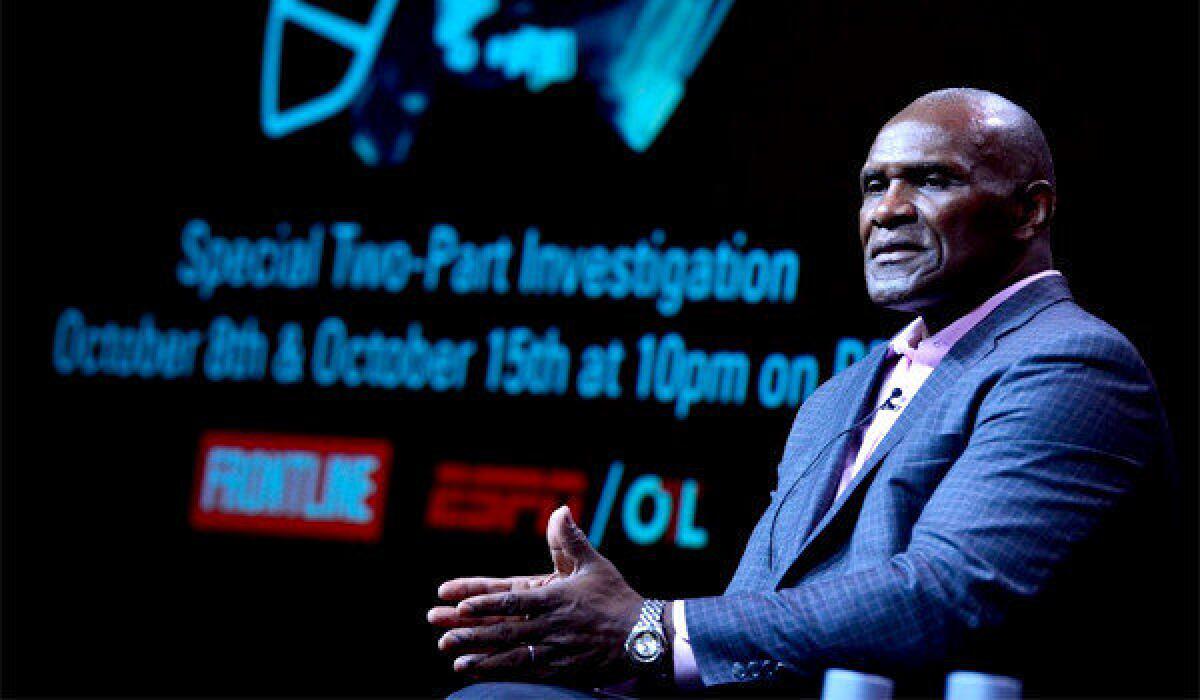

And the football concussions portrayed by PBS’ ”League of Denial,” which Dwyre dubs a “journalistic masterpiece,” serve as the impetus for his column. But not until more than 70 minutes has passed does “League of Denial” permit a critic to speak. Dwyre’s “masterpiece of documentation and reasoned journalism” never bothers to inform viewers that several of its talking heads served as paid consultants to the retired players’ lawsuit against the league, even as it periodically discredits critical voices as “NFL doctors.” Worst of all, the inconvenient truth that the vast majority of brain scientists disagree with the film’s central thesis -- that science shows that football leads to chronic traumatic encephalopathy, or CTE -- gets left on the cutting-room floor.

For anyone remotely familiar with the medical literature, the academic backlash against journalistic alarmism represented by “League of Denial” has been hard to miss. “Sensational media attention has surrounded chronic traumatic encephalopathy,” warns a new article in the journal Behavioral Sciences and the Law. A 2011 article in the American Journal of Bioethics: Neuroscience asks: “Why have the prevailing winds of popular culture shifted toward acceptance of a causal link between concussion and CTE without valid scientific evidence of such a link? Media sensationalism in the context of a small number of high-profile cases has undoubtedly played a role.” A new article in the Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society opens by contrasting “widespread media coverage and speculation” with “very little in the way of peer-reviewed data” on sports head trauma.

These and other recent academic articles echo the consensus statement from last year’s International Conference on Concussion in Sport, which declares that “a cause-and-effect relationship has not yet been demonstrated between CTE and concussions and exposure to contact sports” -- a statement diametrically at odds with the animating premise of “League of Denial.” The consensus statement conspicuously recognizes CTE “fears” hyped by “media pressure.”

Journalists may not be reading the doctors, but the doctors are clearly reading the journalists. Just as football’s critics exaggerate science to buttress their prejudices, they ignore science undermining their thesis. The Mayo Clinic, for instance, in a 2012 study found neurological disease rates for midcentury high school football players on par with their peers in the glee club, choir and band members. Science contradicts the alarmist notion that the sad outcomes for a few NFL competitors will be the outcomes for varsity lettermen.

Instead of celebrating a safer game, the game’s enemies offer louder criticisms of smaller injuries. Even flag football isn’t safe from their crusade. What is the endgame: checkers?

The bubble-wrapped existence fostered by a neurotic society afraid of its own shadow has contributed to the teenage obesity epidemic. By taking away group activities such as powder-puff games and boarding-school football, we exacerbate the social isolation experienced by today’s youngsters through declining birthrates, impersonal digital intermediaries and electronic playmates. Boys lacking adequate outlets to route their innate energy spark too-frequent Ritalin and Adderall prescriptions.

Abolishing football means that teenage boys experiencing the sudden rush of testosterone will pursue other activities, some unhealthy, to channel their natural aggression that we unnaturally suppress.

Perhaps, as Dwyre writes, the NFL deserves to be devastated. But the 4 million kids playing America’s game, devastated by the unintended consequences of the anti-football crusade, don’t deserve to grow up without the gridiron. They deserve the mud, the exhilaration, the competition, the outdoors. We give them xBox instead.

There are plenty of reasons to encourage children to play football as they have done for more than a century. The best reason serves as its own encouragement: Football is fun. The killjoys seeking to take the prolate spheroid and go home surely aren’t.

ALSO:

Redskins: No harm, no foul, Mr. Costas

Tea party backlash: Protest signs to cheer you up

Daniel J. Flynn is the author of “The War on Football: Saving America’s Game” (Regnery, 2013).

If you would like to write a full-length response to a recent Times article, editorial or Op-Ed and would like to participate in Blowback, here are our FAQs and submission policy.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.