Helen Gurley Brown, Cosmo and the limits of stiletto lib

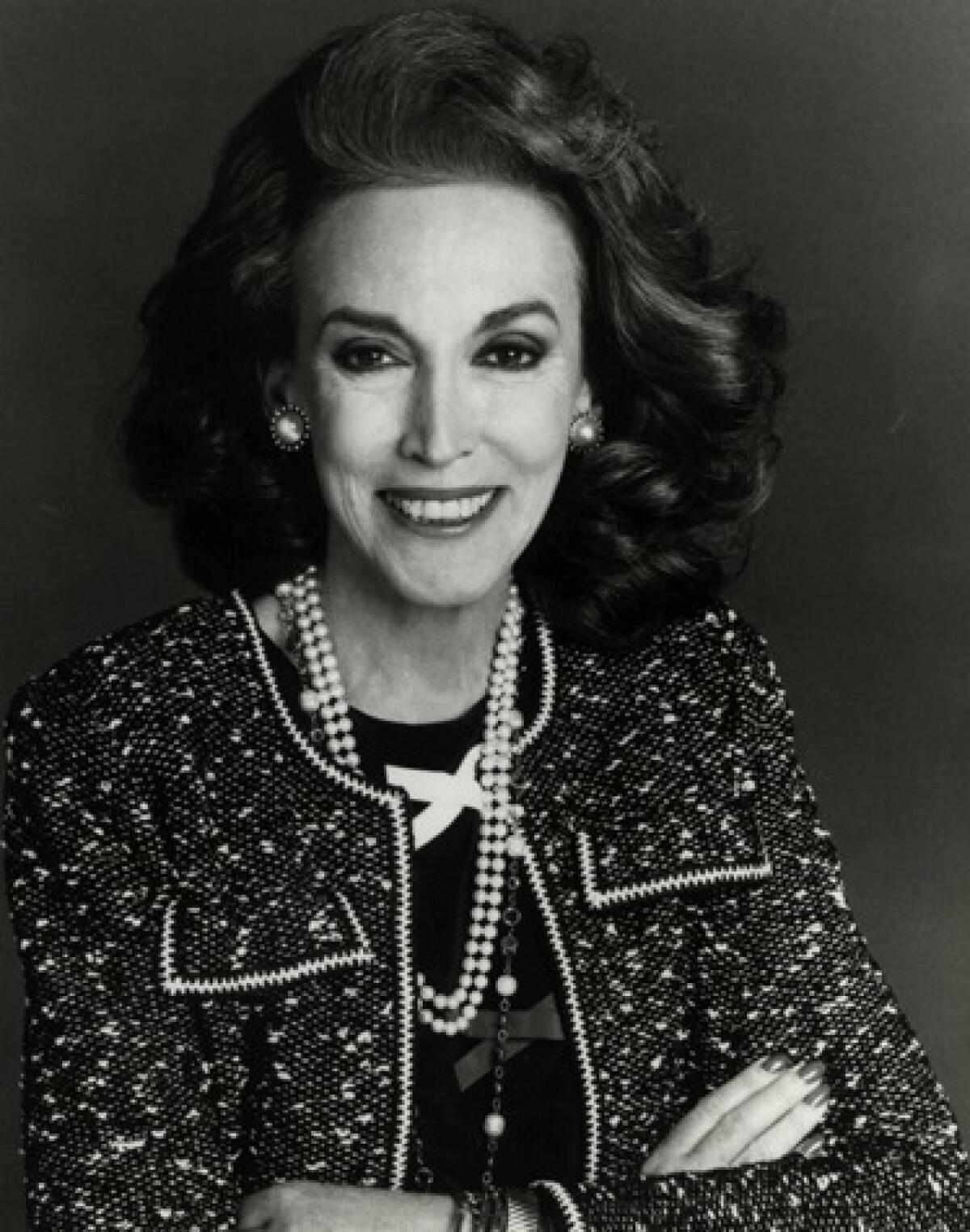

Helen Gurley Brown, legendary editor of Cosmopolitan and doyenne of stiletto-heeled self-empowerment, died Monday at 90. The author of “Sex and the Single Girl,” Brown was widely credited for revolutionizing the precepts of women’s media, transforming a melange of recipes and homemaking tips into an unapologetic celebration of sexual, social and professional striving captured in cover lines like “Four Fab New Vibrators” and “Get Hit On All The Time.”

Before word of Brown’s death took hold Monday, another big story in the news revealed that, for the first time in two decades, a woman —CNN’sCandy Crowley — would be moderating a presidential debate. Many reports cited a campaign waged by three teenage girls, whose online petition on the subject collected more than 115,000 signatures.

The campaign’s victory was met with congratulatory nods not only to “grrl power” but to what appears to be a rather divine partnership between Change.org, which hosts petitions for every imaginable cause, and rabble-rousing young females. In April, 14-year-old Julia Bluhm collected 84,000 signatures demanding that Seventeen magazine allow one photo spread per issue to remain digitally unaltered. In response, in an August editor’s note, Seventeen promised to “never change girls’ body or face shapes.” Admittedly, that leaves considerable room for interpretation, but the fact that the magazine went so far as to draw up a “Body Peace Treaty” suggests that future generations might have less masochistic relationships with their lady mags than cohorts past.

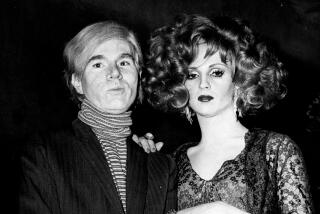

PHOTOS: Helen Gurley Brown | 1922-2012

I’m not being hyperbolic when I talk about masochism. For all the lip service paid to the ego-affirming qualities of women’s magazines, the truth is these publications walk a fine line between offering self-help and engendering self-hate. That’s why the postmortem anointing of Brown as an unimpeachable feminist heroine — “pathfinder” and “icon of the sisterhood” were among the countless panegyrics on Twitter — is at once predictable and puzzling. Not because Brown wasn’t a pioneering role model in her way, but because her vision of the emancipated woman — a self-made but coquettish striver for whom professional achievement often went hand in hand with the sexual manipulation of men — was not all that different from the Stepford Wife model from which the emancipation was ostensibly taking place.

Sure, the trappings seemed diametrically opposed: sex positions instead of souffle recipes, the semen facial (“makes a fine mask — and he’ll be pleased,” Brown famously advised) instead of cold cream. And, to some ears, there’s enough archness in play to preclude getting all worked up about the patriarchy.

But here’s what’s always been the ideological rub for the “Cosmo Girl”: Just because she’s presented as a willing and enthusiastic participant in her objectification, just because she chooses her thong underwear and stratospherically high heels, doesn’t mean she’s living under any less tyranny than the women who came before her. If anything, the pretense of choice turns her into her own most tyrannical force.

And there’s the ideological rub for Brown: By taking the concept of independence and reframing it as a lifestyle, one in which fabulousness is essentially code for materialism and external self-improvement, Brown’s vision was less a revolution than a brilliant marketing scheme.

There’s something to be said for that, just as there’s something to be said for Brown’s spectacular transcendence of her impoverished, hillbilly, “mouseburger” roots and the way she delivered a jolt of entitlement to women who expected little of their lives. But to do justice to Brown’s legacy, it seems imperative to recognize that she wreaked havoc on the trail even as she blazed it.

Call her an icon. Call her, even, a feminist (in my book she qualifies). But to pretend that the fantasies in which Brown trafficked, particularly those that whispered sweet doctrines of “look hot and the rest will follow,” haven’t done their share of damage is to underestimate the scope of her influence.

It is to ignore the fact that any woman moderating a presidential debate will endure a referendum on her looks as well as her skills. It is to be so resigned to the glorification of female body proportions not found in nature that it takes a 14-year-old to tell a magazine to knock it off. Most of all, it is to overlook the uneasy resonance of one of Brown’s best-known bon mots: “Good girls go to heaven. Bad girls go everywhere.”

And indeed, everywhere you look, there she is.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.