Opinion: Was Apple’s FairPlay worse for the record labels than for consumers?

Melanie Wilson and Marianna Rosen’s lawsuit against Apple finally made it to federal court this week, nearly a decade after they accused the company of using its iTunes software and iPod music players to impede competition and hurt consumers. But they may not get the chance to present their case to a jury, as U.S. District Judge Yvonne Gonzalez Rogers questioned whether Wilson and Rosen had owned any of the iPod models at issue.

Even if the lawsuit is dismissed, though, the case offers a valuable reminder of what happens when content companies embrace proprietary anti-piracy technology. The risk is that a company such as Apple will use “digital rights management” tools to protect its market share, not content, at the expense of innovation and opportunity.

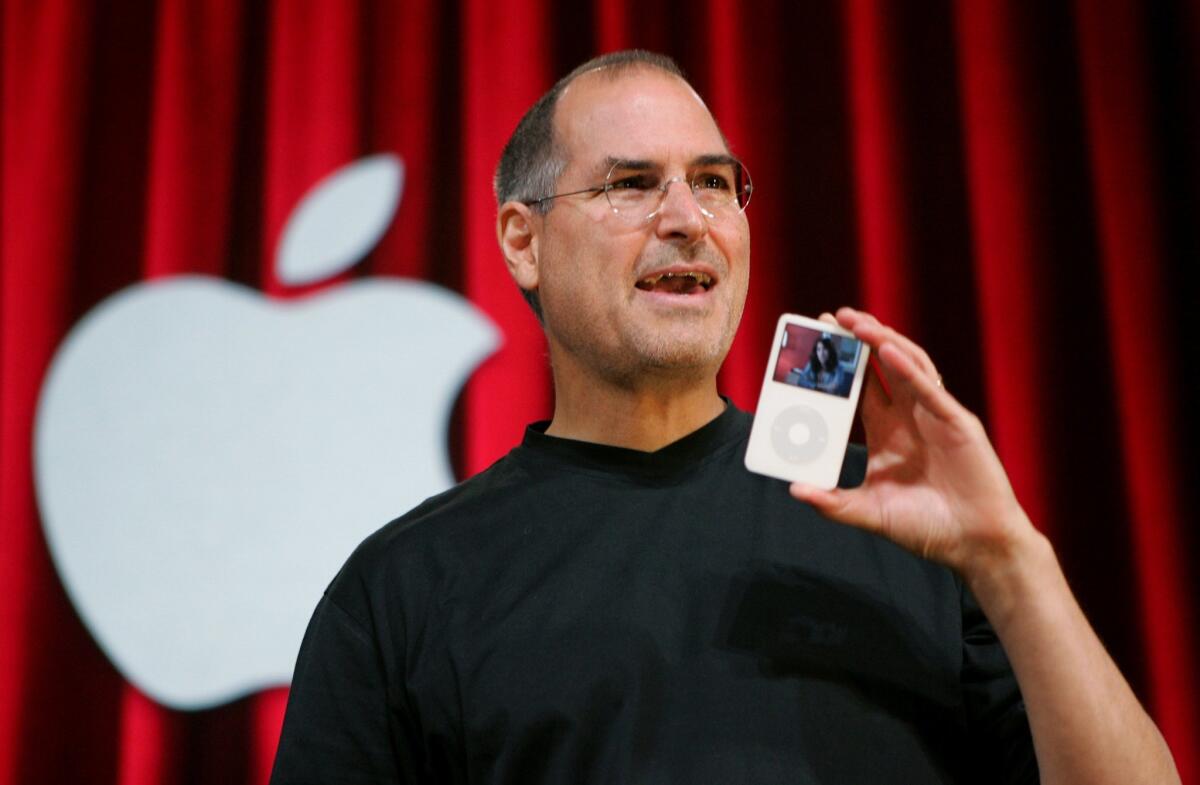

Apple’s DRM was called FairPlay, which limited the number of copies that people could make of the songs they bought on the iTunes store. Introduced when the iTunes store was launched in 2003, FairPlay also ensured that only an Apple device could connect to iTunes, and that only iTunes could be used to install music purchased from Apple onto a portable player.

Rocked by file sharing and plummeting CD sales, the labels were so delighted at the thought of Apple users filling their iPods with purchased tracks instead of stolen ones that they OKd the company’s use of a proprietary DRM. And why not? The nascent market for legitimate music downloads was riddled with proprietary DRMs, including Liquid Audio’s, RealNetworks’ and Microsoft’s.

And in the short term, at least, things worked out well for the industry and consumers. Reassured by Apple’s copy protection, the labels made far more songs available than ever before, making downloadable music a real alternative to CDs for the first time. In response, the sale of downloadable tracks grew at an astonishing pace.

It was only later, when Apple’s dominance over the portable music player market helped it become even more dominant in music sales, that top label executives started to regret what they’d done. FairPlay’s gatekeeper role over the wildly popular iPods gave Apple so much leverage in negotiations with the labels -- it wielded enormous influence over the price, packaging, retail margin and other essential terms for downloadable music sales.

The labels eventually did the only thing they could to keep competition alive among online music retailers: they gave up on DRM. Steve Jobs himself goaded them into doing it, in part because Apple was catching flak from European authorities over iTunes’ lack of interoperability, in part because some of the labels were circulating plans to let other retailers sell DRM-free MP3s.

In the meantime, FairPlay became a target for Apple competitors, such as RealNetworks, and hackers, such as Jon Lech “DVD Jon” Johansen, who developed ways to play songs with non-Apple DRMs on iPods and to play songs wrapped in Apple’s DRM on other manufacturers’ devices.

That’s where Wilson and Rosen’s lawsuit comes in. The lawsuit alleges that Apple issued a series of iTunes updates that forced unsuspecting users to clear their iPods of tracks bought from rivals’ stores. Apple argues that the updates were needed to protect against piracy, as well as to add new features. The lawsuit claims that the updates were designed to protect Apple’s market share and increase its profit margin.

The claims apply only to iPods sold between September 2006 and March 2009, however, and Apple says the two plaintiffs didn’t buy their devices during that period. Wilson has dropped out of the case and Apple has sought to dismiss the rest of the lawsuit, but lawyers for the plaintiffs argue that the class includes about 8 million other purchasers. Judge Rogers is expected to address the issue again Monday.

Apple’s use of a proprietary DRM had one other, major, affect on the digital music market. Based on Jobs’ conviction that “people want to own their music,” FairPlay didn’t support online music services that let people download temporary copies of songs from a vast online jukebox. That opposition kept services such as Rhapsody and Yahoo Music Unlimited from gaining much, if any, traction with consumers. Think of it this way: what’s the point in signing up for a music service if it didn’t work with your favorite music player?

The arrival of smartphones and apps solved the DRM compatibility problem, which helps explain why the number of subscribers to services such as Spotify and Rhapsody has skyrocketed. It’s impossible to know where those numbers would be had Apple embraced an interoperable DRM, or if FairPlay had been friendly to music subscriptions, but they certainly wouldn’t be lower.

It’s tempting to think that had iPods supported the likes of Rhapsody and Napster (the legitimate, paid version) in their infancy, the music industry wouldn’t have been so badly damaged by piracy. After all, according to Spotify, the revenue-per-customer generated by its service is considerably higher than the average amount spent by U.S. consumers on music.

Surveys have shown that the iPod owners filled only a small fraction of their devices’ hard drive with music bought from iTunes. In other words, they were filling their iPods mainly with free music -- possibly ripped from their own CD collections, but in many cases amassed through illegal downloads from file-sharing networks. What if they could have loaded them with gigabytes of music for $10 a month? Where would the music industry be today?

Thanks to the labels’ acquiescence to proprietary DRMs, we’ll never know.

Follow Healey’s intermittent Twitter feed: @jcahealey

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.