Doris Lessing opened our eyes to apartheid too

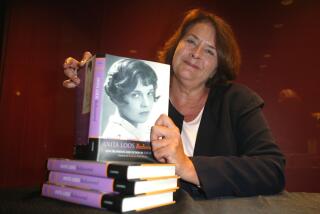

Nobel Prize-winning author Doris Lessing, who died this week at 94, is best known, and appropriately so, as a ground-breaking feminist writer. As the L.A. Times’ Kim Murphy wrote in Lessing’s obituary, her “richly imagined, scathingly perceptive novels helped define early feminism and the doomed idealism of the postwar generation.”

Lessing’s signature work, “The Golden Notebook,” Murphy wrote, suggested that humanity, male and female, is driven by a common yearning: “Everybody in the world is thinking: I wish there was just one other person I could really talk to, who would really understand me, who’d be kind to me,” one of the characters said. “That’s what people really want, if they’re telling the truth.”

But to me, as a teenager in suburban California, Lessing opened another door too. Along with Nadine Gordimer and J.M. Coetzee, she told me shocking stories about human conditions half a world away from my sunny middle-class neighborhood, eye-opening scenes of southern Africa, of men and women, of race and apartheid.

As David Ulin in Jacket Copy wrote:

“Lessing was a political writer from the moment her first novel, ‘The Grass Is Singing,’ appeared in 1950. The book, published after she immigrated to England from colonial Rhodesia — where she’d been raised — involves a white farmer’s wife who has an affair with a black servant; it was an audacious way to begin a career.”

Indeed it was. Those stories mesmerized me.

And it wasn’t dramatized history I was reading; it wasn’t “the way it used to be.” Those cruel characters and bloody confrontations were seemingly plucked from the headlines of the day. Coming out of America’s turbulent civil rights era of the 1960s, it seemed so wrong, so improbable, that such a racially imbalanced society was still prospering across the ocean. But it was, because there on the front pages were teenagers my age rebelling in South Africa’s Soweto township.

Lessing and her fellow writers of fiction fleshed out the gaps in the news reports. What sparked this divide? Who created this system? Who were these people? The blunt and sometimes brutal stories provided some explanations, some illumination.

And those writers kept looking prophetic as anti-apartheid and “Divest Now” protests shook my college campus.

So, on the day the finally freed Nelson Mandela voted in a general election, for the first time in his life -- for himself as president -- I thought of the brave words of Lessing and in Gordimer’s “Burger’s Daughter” and in Coetzee’s “In the Heart of the Country.”

Irascible as she was, Lessing would probably scoff at the appreciations coming her way.

So enough; I’m glad she spoke to so many of us then; she can have the last word now:

“How are we, our minds, going to change with the new Internet, which has seduced a whole generation into its inanities, so that even quite reasonable people will confess that once they are hooked, it is hard to cut free, and they may find a whole day has passed in blogging?”

ALSO:

Goldberg: Oprah, Obama and the racism dodge

‘Selfies’ choice: Word of the Year or sign of the Apocalypse?

Methodist pastor: Expect defiance on gay marriage to carry a price

Sara Lessley is a freelance journalist and editing coach in Los Angeles.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.