Opinion: For Scotland, and Ireland, independence just ain’t what it used to be

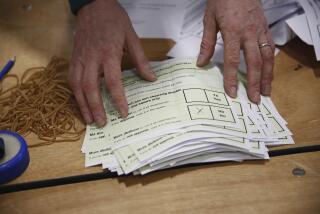

In September, inhabitants of Scotland will vote on independence from the United Kingdom. On Tuesday, Queen Elizabeth II warmly welcomed to Windsor Castle the president of the Republic of Ireland, which declared its full independence from British rule in 1937.

The political establishment in Britain (including, it is assumed, the queen) is vehemently opposed to Scottish independence. But it long ago resigned itself to the independence of the Irish Republic. More than that, it has expressed a willingness to have British-ruled Northern Ireland reunite with the rest of the island if that’s the preference of a majority of Northern Ireland’s population.

Both Scotland and Ireland are occupied largely by Celts, whose original Gaelic languages are still spoken by a minority of the population. Both are religiously different from England. In Scotland, the majority (and established) faith is Presbyterianism. Ireland is predominantly Roman Catholic, though the church in recent years has lost its privileged position.

So why would Britain object to Scottish independence when it has accepted Irish independence? Or turn the question around: If it makes sense for Scotland to remain in the United Kingdom, why shouldn’t Ireland rejoin it on similar terms?

After all, Scotland, even as a part of the United Kingdom, has retained its own legal and educational systems as well as its own established church. And the cultural and linguistic ties between Ireland and England are arguably as close as the ones that bind England and Scotland.

Finally, like the United Kingdom, Ireland is part of the European Union, a political superstructure that has transformed traditional notions of sovereignty and independence.

The short answer to why Ireland is different from Scotland is that historically the Irish were reluctant and repressed subjects of the crown, while the Scots entered the union voluntarily and as equals. Catholics in Ireland were subject to penal laws; Presbyterianism in Scotland was the established religion. There is no Scottish equivalent to the Irish potato famine.

Given that history, it’s understandable that Ireland wasn’t content with “home rule” or a “free state” that was still part of the British Commonwealth. (That transitional arrangement lasted from 1921 to 1937.) History also helps to explain Irish neutrality in World War II. And while Canadians and Australians might not object to recognizing Elizabeth as their symbolic sovereign, the idea is unpalatable to a lot of people in Ireland, even now.

Yet, even as an independent nation, the Irish Republic is intimately interconnected with England: politically, economically and culturally. The same would be true of an independent Scotland, which conceivably might keep both the British pound and the British monarch.

The truth is that independence ain’t what it used to be, and not just in the British Isles.

ALSO:

Time to expose the CIA’s ‘dark side’

Paul Ryan the anti-Robin Hood: Robbing the poor to help the rich

Follow Michael McGough on Twitter @MichaelMcGough3

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.