Opinion: The smart but silent majority on vaccinations begins to roar

Up until this latest measles outbreak, it seemed as though the anti-vaccination parents and their enablers were the more vocal group. They were, after all, the small minority swimming against the trend. There was little reason for the majority to yell back.

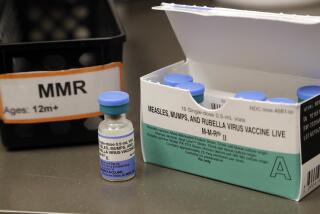

But then the numbers of anti-vaxxers grew — still a very small minority, but enough to tip the public, at least in some areas, out of the protection of herd immunity, when enough people are immune to a disease to protect those who are too young or too frail to be vaccinated, or whose vaccinations did not provide immunity. (The measles vaccine is 97% effective — which means a small number of people won’t receive protection from it.)

And we’re feeling that tipping point as the number of cases of childhood illnesses, once virtually banished, makes its mark this year, closing a child-care center, sending high school students home from school and taking the number of measles cases to numbers not generally seen.

On top of that, the recent death from whooping cough of a newborn in Santa Barbara County — a baby too young to have been vaccinated — has sent shock waves through pediatricians’ offices there. One pregnant woman there recently told me that her doctor laid down the law: It is not neurotic to be neurotic about unvaccinated people in her baby’s presence. All visitors are to be queried about their vaccination status. If they aren’t vaccinated, or aren’t sure, they don’t come into the house, manners be damned. And future play dates will include questions about whether the friend is vaccinated.

Of course, babies shouldn’t be kept in bubbles throughout their first year of life, but new parents are left to fret over how much exposure is too much exposure, and how much protection is overprotection. That’s especially true in child-care settings. This level of concern wasn’t necessary until a critical number of parents stopped vaccinating.

As a result, we’re starting to see a more vocal backlash against the anti-vaccine movement. More doctors are “firing” young patients whose parents refuse to vaccinate them. Sometimes that’s because the doctors don’t want to see themselves as allies in the anti-vaccine movement; other times it’s because the parents of other children are raising alarm about the possibility of an infected child hanging out in the waiting room. The voices of those doctors, parents and alarmed public-health officials were enough to make New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie back off from some mealy-mouthed pronouncement he made about balancing public health concerns with parental choice, and to make Kentucky Sen. Rand Paul back off from his irresponsible assertion that he’s “heard of” cases where vaccination caused severe mental disorders. Heard from where? From whom? With what scientific evidence?

A new California bill by Sens. Richard Pan (D-Sacramento) and Ben Allen (D-Santa Monica) would attempt to latch on to the rising sense of indignation among parents who vaccinate by requiring schools to publicly report the numbers of students who are fully vaccinated. In the pockets of low vaccination rates — and Santa Barbara County has some of the biggest — this provides parents with the ammunition to raise a ruckus. And although the identity of unvaccinated children would of course be confidential, that societal pressure within the local context has the power to change behaviors — especially if it also pressures schools, which have been shamefully lax about following through on partly-vaccinated students despite laws requiring otherwise, to start pressing parents to finish the job.

But this is still tinkering around the edges of the problem. Though parents’ choice is honored in many cases involving their own children, there is no inherent right to endanger other children. California, for all its progressivism, is behind the pack when it comes to requiring vaccination for public school attendance, by retaining an exemption for parents who say their personal beliefs run counter to it. Parents don’t get to say that their personal beliefs run counter to giving their children an education; schooling is compulsory in this and every other state. And raising an ignorant child doesn’t have a direct impact on others.

Thirty-one states have eliminated the personal-belief exemption. Most of those allow exemptions for religious beliefs. But a couple — Mississippi and West Virginia — don’t allow even that, granting exemptions only when there is a medical reason, such as an allergy to an ingredient in vaccines, or a disease causing a weakened immune system in the child. And yet in those states, the concept of parental rights has not collapsed like a shaky roof in a storm. They just don’t have measles in Mississippi.

Pan’s office says there’s a lot more to the bill than just the public notice, but they refuse to reveal more until Wednesday. We’ll see.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion and Facebook

MORE FROM OPINION:

How secular family values stack up

The lesson behind Robin Williams’ will

A natural argument for the birth control pill

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.