Editorial: Reopening California schools is dangerous. But so is letting kids go a year without learning

With COVID-19 cases at very low levels within its borders, Israel fully reopened its schools in mid-May. By the end of the month, 130 students at a Jerusalem high school had tested positive for the virus, setting off a flurry of quarantines for people who’d had physical contact with the students and the closure of dozens of schools.

This is the kind of outcome American parents dread as they contemplate sending their children back to school sometime this summer or fall.

It’s a troubling scenario, but so is the remote-learning experience of the past three months. The reality is, more kids will do better if schools reopen than if they continue online-only classes. But regardless of how we proceed, we must do better.

With little direction or help from federal and state governments, online K-12 instruction was spotty. Some school districts, such as Los Angeles Unified, geared up practically overnight and started feeding their communities as well. Others, including Chicago Public Schools, spent weeks getting ready yet were still woefully underprepared when they finally got going.

Teacher agreements nationwide, including in L.A. Unified, were modified to reduce the number of hours of instruction required to finish the school year, and live lessons were often optional. Some teachers sweated bullets to conduct engaging classes and make sure students understood the material. Others handed out online assignments with barely any student contact. Parents took on new roles as teachers or found themselves as overwhelmed as their kids. Some students simply disappeared from view, never logging in.

Two recent studies found that students made little to no progress in their studies from the point when schools closed. Affluent students were the most likely to have made significant gains in learning, low-income students the least. Energetic teachers could make a difference, but they couldn’t magically surmount the hurdles faced by disadvantaged Black and Latino students, such as severe financial stresses, language barriers and parents who weren’t available to help them. Despite the efforts of many school districts, too many students still lacked access to computers and broadband connections. Softening of traditional school grades might have made learning seem less urgent.

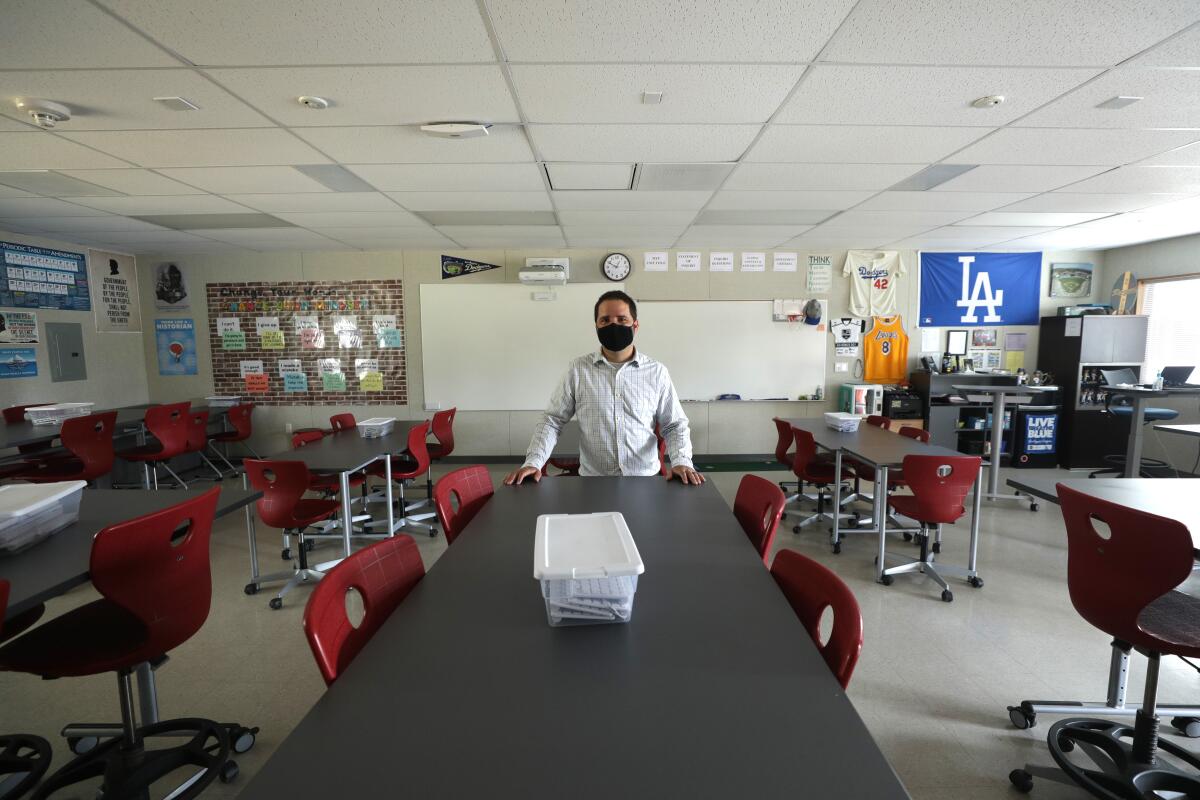

Three months of unprecedented remote instruction for masses of students have worn out parents, teachers and administrators. But bringing students back to campus will multiply both the effort required and the disruption. Under new California and federal guidelines, the schools of 2020-21 would look something like this: classrooms with half as many students or even less, all desks facing forward, no shared supplies, marks on the floor for lining up at safe distances, cloth masks on staff and students, lunches eaten at desks instead of in lunchrooms.

Virtual field trips would replace real ones. Assemblies and football games would be unlikely. In-person classes might happen every other day, alternating with online lessons. Bus riders would sit alone in their seats, every other row. Temperature checks would be administered before anyone entered campus.

Teachers, many of whom are older or have health issues that make COVID-19 more dangerous to them, aren’t fans of the plan. A USA Today/Ipsos poll found that one in five said they’d quit rather than return to campuses. They have company. A separate poll found that most parents don’t want schools to reopen until safety is certain. Affluent parents are especially likely to say they would not send their children back to school if it reopened.

In a way, that might be a good thing. If the number of students needs to be sharply limited on campus, having some stay home altogether makes it easier. But let’s not fool ourselves: Children whose parents have the resources to home-school them are going to continue forging ahead; those attending schools where their teachers wear face shields and mingling and interaction are limited will have a less-than-optimal learning environment. The disparities between rich and poor, and the gaps between white, black and brown students, are going to grow after years spent trying to narrow them.

And yet, if schools can carry it off, in-person schooling is a big improvement for many students over remote learning. Class sizes would be smaller, and kids would experience more than just lessons. They would receive companionship, connection to a bigger community, physical activity and more direct help mastering their lessons.

But the “ifs” are big ones. Gov. Gavin Newsom’s current budget contains draconian cuts to education at the same time that schools must pay for masks, hand sanitizer, temperature checks, more bus trips and the like. In Los Angeles and much of the rest of the nation, we have not managed to bring down COVID-19 cases to nearly the level that Israel did before it reopened schools. That raises our chances of school-based outbreaks. Administrators worry about liability. If they can’t afford the needed testing and so forth, will they be blamed for the infections that ensue?

Massive federal aid is needed. Aside from expenditures on public health and economic relief, it’s hard to imagine a higher priority for the nation than its education system. Neither party wins by starving public schools or making them less safe.

For all the very real budget problems facing Sacramento, state leaders too can soften the blow. The state funds schools through a formula based on student attendance. Rather than sticking to that formula, California should commit to spending the full sum it has allocated for K-12 education regardless of how many students actually attend and direct the funds to the students who have fallen furthest behind. If large numbers of parents switch to home schooling and overall enrollment drops considerably, that would mean more money for those on campus. Good.

Finally, the central theme for the start of the school year should be preparation. Educators could not have foreseen the sudden closure of their campuses in March, but the same can’t be said looking forward. A resurgence in COVID-19 cases could force shutdowns in autumn or winter.

The new school year should start with equipping all students with devices and broadband for distance learning and instruction on how to use them. In-school lessons should rehearse students in remote instruction, with help for parents setting up and operating the smart devices that their kids bring home. Teachers should work with families on multiple ways to reach them if students don’t log in for lessons or assignments.

Teachers also need training in how to teach online — keeping kids engaged via computer screen is much tougher than in a classroom — with at least some live lessons and more instructional hours required; it would help if the California Teachers Assn. agreed to this. Those at risk need off-campus jobs that will keep them safe; those who have young children need well-run child care if schools are closed. It will help if students are alternating days on and off campus; teachers will have more opportunity to practice their skills. Real grades instead of pass/fail or an-A-for-everybody policies would motivate more students to put in the work.

This spring was tough. Reopening schools will almost certainly be tougher. But leaving students to stumble through another year without real learning is unacceptable.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.