Charlie Hebdo cartoonists are casualties in Islam’s identity crisis

On Tuesday, I had lunch at a small Persian cafe in downtown Los Angeles with my friend Nik Kowsar. Nik is an Iranian cartoonist who fled his home country more than a decade ago after being threatened with death because he drew an ayatollah in the image of a crocodile.

Nik still is considered an enemy by the Islamic regime in Tehran. The United States has provided him a safe haven, though, and he has a successful career working as a journalist and cartoonist in Washington, D.C. His work still finds its way back to Iran.

Speaking in Persian to the cafe owner, Nik ordered up an array of Iranian dishes that covered the table. As we dug into the banquet, we talked -- and, of course, we discussed the cartoonists murdered by terrorists in the Paris headquarters of the satire magazine Charlie Hebdo.

The supposed provocation for that incident was a string of rude caricatures of Muhammad published by the magazine. Two disaffected young Muslim men from the gritty Paris suburbs took it upon themselves to gun down Charlie Hebdo staffers because of this alleged offense to their faith. They believed that the Koran forbids any criticism or visual representation of the prophet. Charlie Hebdo’s cartoonists had done both.

Any value system that says people should die for a drawing is, of course, depraved. It is yet another example of fanatics seizing upon a taboo to justify their crimes. Nik told me there is at least one place in the world where portrayals of Muhammad in paintings and posters is quite common: Iran. That’s right, in the world’s largest Shiite Muslim nation, nobody is being punished or killed for displaying pictures of the prophet. Cartoons, obviously, would be judged differently and, in Muslim countries from Niger to Pakistan, mobs have responded to the Charlie Hebdo cartoons with rioting, shootings and church burnings.

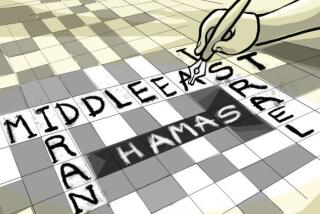

The truth is, cartoons of Muhammad are merely a convenient excuse to take to the streets to vent frustration and anger. There is plenty to be frustrated and angry about in much of the Muslim world -- corrupt and oppressive governments, high unemployment, a sense of disenfranchisement and alienation -- but a significant part of the fury is the product of a religion in crisis.

There is not one Islam, there are many. Believers span a wide spectrum. At one end are the liberal, peaceful, deeply humanitarian Muslim men and women who, in the wake of the Paris killings, have been all over American TV defending their benign reading of the Koran and condemning those who murder, rape, enslave, torture and crucify in the name of Allah. On the other end are the psychopaths of Islamic State who took a significant amount of time on camera offering a religious justification before setting fire to a captured Jordanian fighter pilot.

The people on the two ends of this spectrum deny that the others are true Muslims. American liberals -- in particular President Obama -- are quick to agree with those on the peaceful end of the issue because it is easier to take the fight to Islamic State terrorists if it is not interpreted as a holy war by Christians against an Islamic sect. But there is no shortage of conservative Muslims in places such as Saudi Arabia, Libya and Pakistan who shun modernist Muslims and agree with the terrorists about most things, even if they abhor a few of their tactics.

Citizens of the westernized world, much to our dismay, are being caught up in a battle for the soul of Islam. Muslims with a multitude of interpretations of their faith are vying with each other amid a complex tangle of tribes, nationalities, sects and political forces. The United States should do what it can to encourage those who seek to bring their religion into the modern world, but Americans dare not be foolish enough to think they can control events or force an outcome. This is a struggle that will take generations to resolve.

Nik Kowsar would love to visit his homeland one day, but the 45-year-old knows it will not be soon. At best, he told me, he will be there with a grandson who is still many years from being born.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.