Nelson Mandela transformed himself and then his nation

I met Nelson Mandela not long after he stepped down as president of South Africa. He was visiting the Gates Foundation in Seattle, and I was part of a group of journalists lucky enough to get the chance to interview him for an hour.

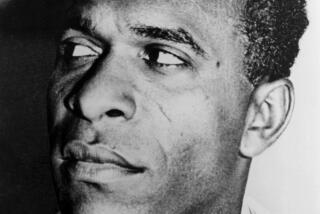

Now, with the news of his death at 95, Mandela is being lauded as the greatest, most charismatic leader of our times and I might be expected to say how amazing it was to be in the man’s presence. But on that day in Seattle, he seemed no more extraordinary than many other people I have met. He had a graceful dignity about him and a humility learned over a lifetime, but he was not physically imposing or remarkably eloquent. He just seemed like a very good man.

And that is something worth remembering as the world media perform a secular canonization of Mandela. He was not a saint or a superman. He had his human failings. He started his adult life as an angry young man with a malleable philosophy that ranged from Methodism to Marxism. He even agreed that his enemies were correct to call him a terrorist.

What turned him into the great man who created a legacy comparable to that of Lincoln or Gandhi was his ability and willingness to broaden his understanding of his fellow human beings and to turn away from hate and toward love. Mandela was a man like any other except in his exemplary capacity to open his heart, even to his enemies.

Mandela said, “Resentment is like drinking poison and then hoping it will kill your enemies.” And he said, “If you want to make peace with your enemy, you have to work with your enemy. Then he becomes your partner.” And, in his autobiography, he said, “No one is born hating another person because of the color of his skin, or his background, or his religion. People must learn to hate, and if they can learn to hate, they can be taught to love, for love comes more naturally to the human heart than its opposite.”

For most people, 27 years in prison would not inspire that sort of philosophy. Most people would be crushed by the experience or consumed by resentment or hellbent on revenge. Mandela’s nearly three decades as a political prisoner were transformative. He transformed himself and, in the process, was able to transform his nation.

It is also worth remembering that Mandela never ceased being a revolutionary. He remained a socialist, an admirer of Fidel Castro. The man now being praised by the likes of George W. Bush was denounced by Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher. He was branded a communist. He was reviled as the antithesis of everything Americans hold dear. Yet he sought nothing more than what our own revolutionaries claimed to fight for in 1776: the right of every person to live free and have an equal voice in the affairs of his country.

Mandela was a militant black man with a raised fist and that scared many people. But the revolution in his heart freed him from narrow ideology or racial enmity and made him able to seek the national reconciliation that led to a more complete liberty for all the citizens of South Africa, no matter the color of their skin. Yes, he was just a man, but he learned a key lesson that most revolutionaries, politicians and world leaders never learn: before you can change the world, you must change yourself.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.