GOP at risk of losing several key governorships at a crucial political moment

Running in a place where Republicans dominate state government and Donald Trump won in 2016, Michigan Atty. Gen. Bill Schuette might have expected an easier path to victory in the upcoming governor’s race.

But at a recent midday press conference on the fringes of downtown Detroit, his allies were outnumbered by protesters outside, who shouted that the GOP nominee should “Go home!,” banged on building windows and hoisted a giant puppet of him scowling. Schuette is trailing badly in polls.

For the record:

7:55 a.m. Oct. 15, 2018An earlier version of this article said district lines were last drawn in 2010. They were drawn after the 2010 census, beginning in 2011.

In similar governor’s races throughout the nation, the GOP’s lock on power is in serious jeopardy as their candidates — in even the reddest states where Democrats have long been an afterthought — struggle ahead of the November midterms.

Some of the states where Republicans risk losing the governor’s office — Michigan, Wisconsin, Illinois, Florida and Ohio, for examples — are known to swing politically, but the trend extends far beyond those states.

Georgia, Iowa, Kansas and South Dakota have all been thrown into the toss-up column by the nonpartisan Cook Political Report, which recently noted that even Oklahoma is not a lock for Republicans.

The timing is bad for the Republicans, emerging as the nation is on the cusp of redrawing voting districts after the 2020 census.

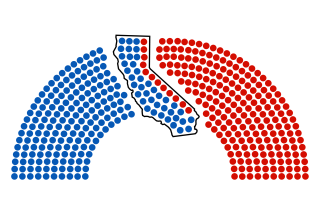

Existing political boundaries heavily favor the GOP, reflecting its control of most state houses and governor’s offices in the most gerrymandered states when lines were last drawn after the 2010 census. The Brennan Center for Justice at New York University School of Law found the boundary lines drawn at that time have enabled Republicans to win as many as 16 extra seats in the House, a substantial share of the party’s 23-seat majority.

Most of that edge comes from a handful of states, including Michigan. Even as that state’s voters are nearly evenly divided in support for Democrats and Republicans, the lines have been drawn to enable Republicans to control nine of the state’s 13 House seats, by concentrating Democrats into the fewest possible districts.

Governors will play a crucial role in redrawing those districts after the 2020 census. Michigan voters are also weighing a November ballot initiative backed by the National Democratic Redistricting Committee that would put a citizens commission in charge of drawing the boundaries.

“It is an exceedingly big year,” said Justin Levitt, a professor of election law at Loyola University who helped run the Justice Department’s civil rights division under President Obama. “Many of the people who will be handed the redistricting pen are up for election.” In many states, governors have veto power over the political maps.

Republican candidates are in trouble this election season for a number of reasons. Trump fatigue is one. Voters like the healthcare workers who showed up to shout down Schuette are part of a re-energized left determined not to see a repeat of 2016, when Trump won what had been considered a reliably blue state in presidential elections by 10,000 votes. Fifty-four percent of Michigan voters disapprove of the president’s job performance, according to one recent poll.

But voters in Michigan and nationwide are bothered by more than just Trump. They are frustrated with escalating healthcare costs, fraying transportation systems and substandard schools in states Republicans have controlled for many years.

“There is some broad fatigue with Republicans in a lot of these states,” said Kyle Kondik, who tracks political races as managing editor of the nonpartisan Sabato’s Crystal Ball.

Even as the economy hums in places like Macomb County, a manufacturing hub outside Detroit where disaffected Obama voters helped drive Trump’s victory, ambivalence runs high.

“I may not even vote,” said Utica resident Helen Kent, an 82-year-old who supported Trump. “I am not excited about any election anymore. The whole world is such a mess.”

Kent was approached last week by a representative with Working America, an AFL-CIO group that has 44 staffers knocking on doors in Macomb to persuade working class Trump voters not to vote Republican this year.

Kent said she still considers herself a big Trump supporter. “I don’t know what he has done or not done,” she said of the president. “I just think he had a lot of publicity against him. If everybody is against someone, I am for them.”

But for Kent and others, the president’s coattails don’t extend to enthusiasm for Schuette.

Utica Mayor Thom Dionne, a police officer who also voted for Trump, said he’ll likely vote for Schuette, who has strong law enforcement backing. But in an interview he sounded impressed by Democratic candidate Gretchen Whitmer.

A top issue on his mind, like that of most voters here, is the miserable state of the roads. Whitmer has been aggressively promoting a plan to raise money for repairs as Schuette, who has positioned himself as an anti-tax crusader, hedges. The roads are so bad in Macomb that potholes have inhibited growth in a county working furiously to lure more defense contracting and next-generation transportation jobs.

“I like that she is trying to fix the roads,” Dionne said. “I would like to see us have even a fraction of the quality of roads they have in Ohio or Kentucky.”

Even Whitmer marveled at how the pothole issue has dominated the campaign. “I never in a million years when I jumped into the race thought I would become the ‘fix the damn roads’ lady,” she said at a lunch meeting of the Macomb County Chamber of Commerce.

During her talk and an interview just before it, Whitmer avoided attacking Trump, who remains popular among some voters in the coalition she is building.

“I hardly ever weigh in on things going on in Washington, D.C.,” she said. Like so many of the Democrats making strong showings in the GOP-dominated Midwest, Whitmer, a former Democratic leader in the state legislature, is the opposite of a firebrand.

Yet these technocrats are catching fire. In Ohio, a recent gubernatorial debate between Democrat Rich Cordray and Republican Mike DeWine was defined by its lack of spark. The race there is a toss-up.

“These are not protest candidates,” said former Michigan Gov. James Blanchard, a Democrat.

Four decades ago, in the aftermath of Watergate, Blanchard said voter anger helped him win a seat in Congress, but he didn’t focus his campaign on Richard Nixon’s misdeeds, which he said would have risked alienating Midwesterners. Many Democrats trying to regain control of governor’s houses in this politically tricky territory are following the same path.

“They are solid, practical Democrats,” Blanchard said. “The Berniecrat wing of the party may not prefer them, but it will support them.”

Schuette’s efforts to stir hot-button national and international issues into the Michigan race, meanwhile, keep falling short.

In an interview, he focused on an 8-year-old tweet from Whitmer’s running mate for lieutenant governor, which blamed Israeli aggression for the rise of Hamas. Schuette called the tweet “disgraceful.”

He suggested Whitmer is a carbon copy of Michigan’s previous female governor, Jennifer Granholm, who pursued a liberal agenda in office and later became the co-chair of Hillary Clinton’s ill-fated transition team. He touted Trump’s tax cuts and trade deals.

The national issue that voters seem to care most about is healthcare, but that’s a problem for Schuette and other Republicans running for governor in GOP-controlled states. As attorney general, Schuette sued at least nine times to block the Affordable Care Act, and he broke with Republican Gov. Rick Snyder to oppose the popular Healthy Michigan program, which expanded Medicaid to cover 660,000 people.

Despite the popularity of Obamacare in Michigan, Schuette continues to attack it.

“Congress hasn’t solved the problem,” he said, “There is not a federal healthcare policy... The federal funding is not indefinite. We have to do something to make sure we help the system.”

Obamacare opposition has become an albatross throughout Republican states. In Wisconsin, it has driven down support for Gov. Scott Walker, the one-time star of the GOP and much talked-about presidential contender who now is in jeopardy of getting voted out of office as he vies for a third term as governor. He is trailing in the polls.

Florida’s rejection of the Medicaid expansion has helped propel the campaign of Democratic gubernatorial nominee Andrew Gillum, an unabashed progressive who supports a Medicare-for-all system and has expanded his base far beyond the left. The Florida race is in a virtual dead heat with polls suggesting a small lead for the Democrat.

Schuette’s plans to curb, rather than expand, government health insurance had long been a reliable talking point for GOP candidates. But it’s doing little to help him lock in voters like Utica’s mayor.

“People need to be taken care of,” Dionne said. “We should probably look at socialized medicine.”

The latest look at the Trump administration and the rest of Washington »

More stories from Evan Halper »

evan.halper@latimes.com | Twitter: @evanhalper

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.