Capitol Journal: Committed to his ethics and transparent governing, George Deukmejian represented the best of American politics

George Deukmejian was a role model for the type of officeholder we desperately need in today’s hyperventilated, polarized politics.

He was a quiet leader who didn’t continually need to hear his own voice.

He was committed to his conservative causes but flexible enough when circumstances changed to tell his political base to take a hike.

He was highly ethical, never touched even by the whiff of scandal.

And very important, given today’s ill manners from top to bottom in politics, Deukmejian was gracious and civil. He respected others and their views.

OK, no one is perfect. He could be a tad thin-skinned, particularly when Los Angeles Times editorials opposed his positions.

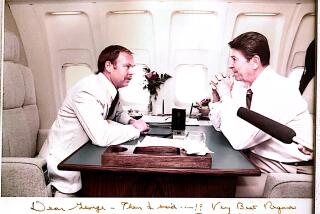

Whatever, Deukmejian never took it out on Times reporters. And my relationship with him couldn’t have been better.

He was a model of transparency, holding a regular news conference every two weeks. He considered it his duty to answer reporters’ questions. The governor also used it as a management tool by requiring department directors to give him a heads-up about any potential embarrassments that might surface.

Deukmejian died Tuesday of natural causes in his modest Long Beach home at age 89.

The son of Armenian immigrants who fled to America to escape genocide by Ottoman Turks, Deukmejian was infused at an early age with a commitment to law and order. That became his No. 1 passion in public office. He wrote legislation restoring the death penalty and mandating “use a gun, go to prison.” He also built eight prisons.

The Republican was first elected to the state Assembly in 1962 and moved to the Senate in 1966, where he became party leader.

Two examples of how California Republicans half a century ago were a different breed than today’s species: New Gov. Ronald Reagan proposed a then-record tax increase to balance the budget, and Deukmejian shepherded the bill through the Legislature. Deukmejian also cast a key Senate vote for the nation’s most liberal abortion rights act, which Reagan signed.

Those were the days when Republican candidates regularly won high offices in California.

Deukmejian was elected state attorney general in 1978 and narrowly defeated L.A. Mayor Tom Bradley in 1982 to become governor. He trounced Bradley in a 1986 rematch.

He was never a bar-hopping reveler like many legislators of both parties in the ‘60s and ‘70s. He’d retire to his simple motel room, maybe open a can of soup and read up on legislation.

“Dull Duke” he was called. He became “Iron Duke” when, as governor, he steadfastly held the lid on Democratic spending.

Apparently he never cursed.

“George never used those words, ever,” says Steve Merksamer, his chief of staff both as governor and attorney general. “And nobody around him used them in his presence. The most he ever would say if he was really, really angry, was maybe ‘damn.’”

Deukmejian’s detest of cursing, Merksamer says, is what led to creation of the “Big 5” — the Capitol’s premier negotiating team consisting of the governor and legislative leaders from both parties.

Coverage of California politics »

Soon after becoming governor, Deukmejian called in the chairmen of both legislative fiscal committees to discuss how to erase a $1.5-billion budget deficit without raising taxes. The governor received a barrage of “F-words,” Merksamer recalls, and was loudly told he had no choice but to raise taxes.

The committee chairmen were dismissed. Merksamer was instructed to never bring them back. Instead, invite the top leaders. This inaugurated the Big 5 concept that lasted about 30 years until Republicans no longer were relevant.

Deukmejian agreed to a “trigger tax.” If the economy remained bad, a half-cent sales tax increase would be triggered. But the economy recovered, erasing the deficit.

The governor occasionally surprised folks by acting against party dogma.

He signed the nation’s first assault weapons ban after a racist with an AK-47 shot up a Stockton schoolyard in 1989, killing five Southeast Asian immigrant children and wounding 30 other kids.

He persuaded the University of California Board of Regents in 1986 to divest pension funds from firms that did business with racist South Africa. The move helped pressure that white-minority country into ending apartheid rule against blacks.

In 1990, he championed a 9-cents-per-gallon gas tax increase that raised $18.5 billion for highway repairs.

Deukmejian also spent a lot more money on public higher education than did his predecessor, Democrat Jerry Brown.

“His avoidance of bombast made few headlines,” says Ken Khachigian, a 1982 campaign advisor and longtime friend. “He did a lot of things people didn’t notice. Because he wasn’t flashy, people tend to forget.”

Here’s one, recalled by Merksamer: In 1983, Deukmejian provided more money for AIDS treatment than 10 states combined. And this was a time when AIDS was particularly controversial.

Two things I particularly remember:

— On a trip to Tokyo, he tried to peddle California rice to Japanese leaders. He was ridiculed by trade experts and journalists, including me. Buying foreign rice conflicted with Japanese culture. But, of course, Deukmejian made the sell. California became a huge supplier of rice to Japan.

— Deukmejian was closely questioned by German business leaders in Bonn about California’s influx of immigrants. Did it affect work force quality? Were they reliable?

“These newcomers provide renewed energy in our state,” the governor replied. “We believe there is strength from ethnic diversity…. They are enthusiastic, willing to work hard, get an education for their children — and we’re very encouraged.”

You might disagree with some of Deukmejian’s policies, but his character and governing style represented the best of American politics.

Follow @LATimesSkelton on Twitter

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.