Early, frequent antibiotic use linked to childhood obesity

Parents and pediatricians will often reach for antibiotics to treat middle ear infections, strep throat, fevers and other common ailments of childhood. But new research suggests that doing so, and prescribing broad-spectrum antibiotics in particular, increases those children’s risk of obesity, at least in early childhood.

A new study finds that babies who got broad-spectrum antibiotics in their first two years of life, or who were prescribed four or more courses of antibiotics in that period, were more likely to be obese at some point between their their second and fifth birthdays than were those who had taken no antibiotics, or who were treated with medications designed to target a narrow spectrum of disease-causing bacteria.

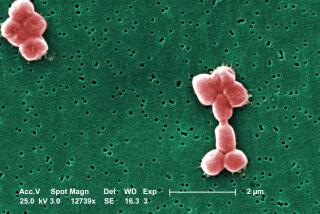

Broad-spectrum antibiotics -- including amoxicillin, tetracycline, streptomycin, moxifloxacin and ciprofloxacin -- are intended for treatment of major systemic infections, in cases where the bacteria causing the illness has not been identified, or where a patient is under attack by a strain of bacteria resistant to standard antibiotics. While they can be highly effective, their antibiotic action is indiscriminate, and beneficial bacteria in the body are often killed off as collateral damage.

The latest study tapped the medical records of 64,580 babies and children in and around Philadelphia. It was published Monday in the journal JAMA Pediatrics.

The heightened risk of obesity linked to antibiotic use was not huge: Babies who got wide-spectrum antibiotics in their first two years were about 11% more likely to be obese between 2 and 5 than were those who got no such drugs. Babies who had four or more courses of any antibiotics in the first two years were also 11% more likely to be obese in early childhood than those who’d had fewer exposures to antibiotics.

But among children who had four or more antibiotics prescriptions, including at least one wide-spectrum antibiotic, the risk of obesity rose to 17%. And the earlier a baby’s exposure to wide-spectrum antibiotic medications, the more likely he or she was, on average, to be obese between age 3 and 5.

The study’s findings add to mounting evidence that the mix of bacteria in the gut plays a potent role in obesity. A welter of research has shown that the diversity of the gut’s population of bacteria appears to confer protection from obesity, while an impoverished microbiotic environment in the gut has been linked to higher risk.

The new research suggests that very early childhood may be a pivotal period in creating a rich and complex mix of microbiota in the gut -- a condition that animal studies as well as epidemiological research have linked to reduced risk of obesity. The gut microbiome is often the unintended victim of chronic exposure to antibiotics, and especially to wide-spectrum antibiotics, which act on a wide range of bacterial families.

“Because the first 24 months of life comprise major shifts in diet, growth and the establishment of intestinal microbiome, this interval may comprise a window of particular susceptibility to antibiotic effects,” the authors wrote. They went on to speculate that by knocking off-course the normal development of bacterial populations inside a child’s gut, the repeated use of antibiotics may alter his or her long-term ability to control weight gain.

The researchers, pediatricians from the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and the University of Pennsylvania’s Perelman School of Medicine, adjusted their findings to reflect known variations in obesity risk that run along ethnic and socioeconomic lines. And they ruled out the possibility that other medications, which might be prescribed more often to children who get antibiotics, might be responsible for the heightened obesity risk.

Around the time of their second birthdays, the weight of babies in the study did not vary in ways that reflected their antibiotics exposure, the researchers noted. Those patterns emerged over time, in their third, fourth and fifth years of life.

The new research underscores that, for some, obesity may have origins in decisions made long before food preferences, eating habits and lifestyle decisions are developed or established.

“This really gives strong evidence that, often, obesity really is not a personal choice,” said Dr. Stephen Cook, associate professor of Pediatrics and Community Health at the University of Rochester Medical Center. Cook, who serves on the executive committee of the American Academy of Pediatrics’ Section on Obesity, said the study makes clear that fighting child obesity “is a much more complicated issue than ‘move more and eat less.’”

For busy pediatricians, the new research is “yet another reason to use antibiotics wisely,” said Dr. Sandra Arnold, associate professor of pediatrics and chief of the division of infectious diseases at University of Tennessee Health Sciences Center.

But, added Arnold, who has authored research on physicians’ antibiotic prescribing practices, that’s easier said than done.

“It’s really hard to get physicians to stop” prescribing antibiotics in circumstances where they’re unlikely to help, said Arnold.

Despite intensive campaigns aimed at reducing physicians’ reliance on antibiotic medications -- and despite the added protections that widespread childhood vaccinations provide -- “really nothing causes doctors to dramatically change their behavior,” she added. Faced with the uncertain prognosis of a feverish child who appears quite ill, said Arnold, even physicians who know better will pull out their pad and write an antibiotic prescription.

Arnold’s own research does suggest that physicians may be more amenable to a key message of the latest research: that whenever possible, narrow-spectrum antibiotics are a better treatment choice for babies than are wide-spectrum ones. While pediatricians are unlikely to resist the urge to prescribe antibiotics in all but the clearest cases of severe bacterial illness, “it seemed you could get better results getting doctors to use narrower-spectrum antibiotics than getting them to stop altogether.”

Watching your own weight, your kids’ and the nation’s? Me too. Follow me on Twitter at @LATMelissaHealy and “like” Los Angeles Times Science & Health on Facebook.