Ice paths slicked with water helped engineers build Forbidden City

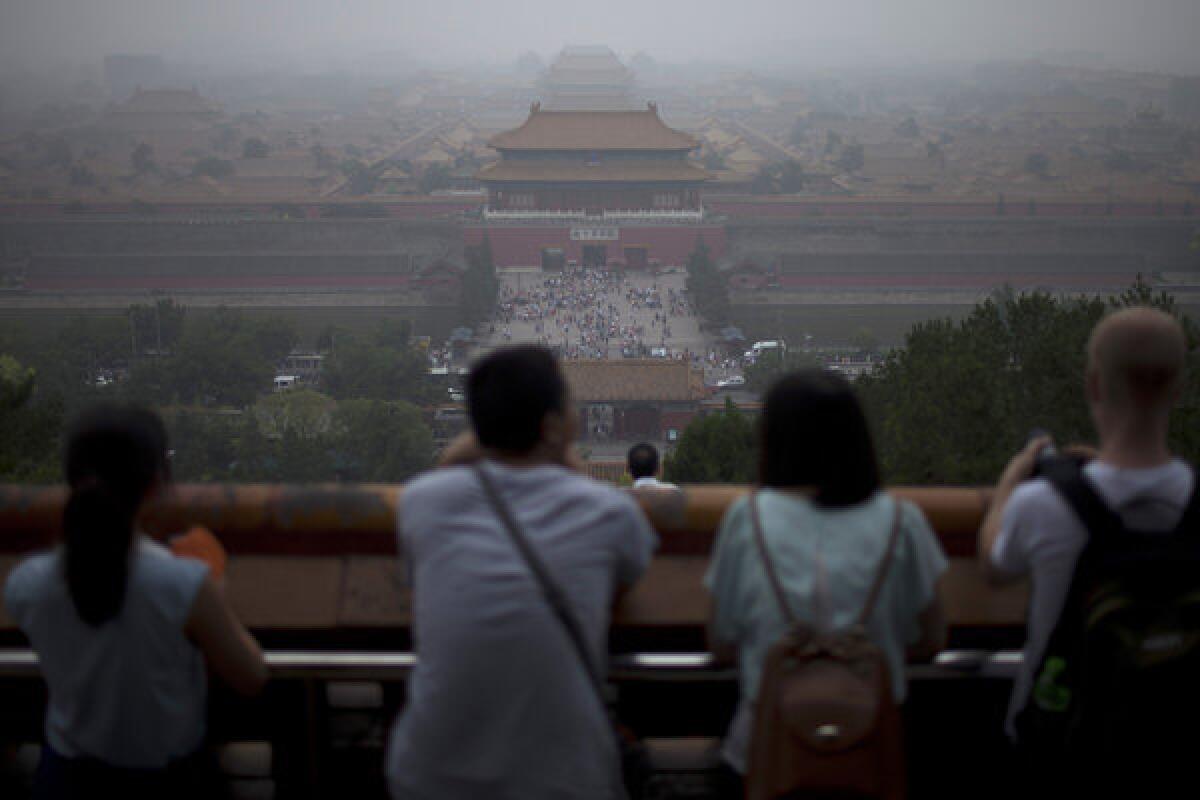

What happens when a group of engineering professsors takes a tour of China’s Forbidden City, the seat of royal power for both the Ming and Qing dynasties? One year later, they publish a paper describing how some of it got built.

In a study published this week in PNAS, friends and colleagues Jiang Li, Hoasheng Chen and Howard A. Stone explain how and why Chinese peasants in the 15th century pulled the heaviest stones used in the Forbidden City along artificial paths of solid ice from quarries more than 45 miles away.

Lying smack-dab in the center of Beijing, the Forbidden City is made of wooden structures that rest on massive stones. The largest stone in the complex is known as the Large Stone Carving, and weighs more than 300 tons.

While touring the site together after a conference, the three researchers noticed a sign that said the stones were moved to the city in the dead of winter, on artificial ice paths.

Why ice paths, they wondered. Why not rollers, or chariots with wheels? After all, wheels have been used in China for thousands of years.

They were the right people to answer the question. Li, a professor at the University of Science and Technology Beijing, and Chen, a professor of Tsinghua University in Beijing, are both tribologists, or scientists who study the science and engineering of friction. Stone studies fluid mechanics at Princeton University.

After digging into the engineering archives from the time, the researchers quickly realized that moving the heaviest stones from the quarry to the Forbidden City with wheels was simply not possible. The wheels at the time were not strong enough to carry such heavy loads, the researchers argue.

Next, the engineers calculated how many people it would take to move the stones on a variety of surfaces. They based their calculations on a 500-year-old document that describes how in 1557, a large stone weighing 123 tons was moved 48 miles over 28 days on a sliding sledge pulled by a team of men.

The researchers report that it would take 1,537 people to pull a 123-ton stone on a sledge along a wood platform. Add water as a lubricant on the wood, and the number of people needed to pull the stone drops to just 354. That’s about the same number of people needed to pull the stone on a sledge on an ice track. But using a sledge on ice that has a water film on it significantly reduces the friction, and that would require just 46 people to move the giant stone.

If the 500-year-old document is correct, the researchers say, the stone was probably pulled on a wooden sledge gliding along a path of lubricated ice. And, wouldn’t you know it, wells were dug every half-kilometer along the road. Perfect for lubricating the ice.

“What I find interesting is how coordinated the whole activity had to be,” said Stone in an interview with The Times. “If you want an ice path, you have to do it when it is cold, and that gives you a finite amount of time. They had to be very good about organizing large numbers of people.”

Ice path logisitcs are just the beginning! Follow me on Twitter for more stories like this.

ALSO:

In online dating, the race card can be a wild card

Earth-like planets may be quite common, relatively close, study says

‘Wasting’ disease turning West Coast starfish to mush; experts stumped