Infertility due to old eggs? An anti-aging pioneer ponders solutions

One of the many ways in which humans’ evolved characteristics clash with a fast-changing post-industrial society can be seen in the female egg.

Even before a woman passes the age of 30, the quality of the oocytes she carries begins a downturn in quality, making conception more difficult and chromosomal abnormalities more likely. And her eggs take a steep dive in quality as she nears 40 -- whether or not she has found a suitable mate, achieved career goals or completed her pre-family to-do list.

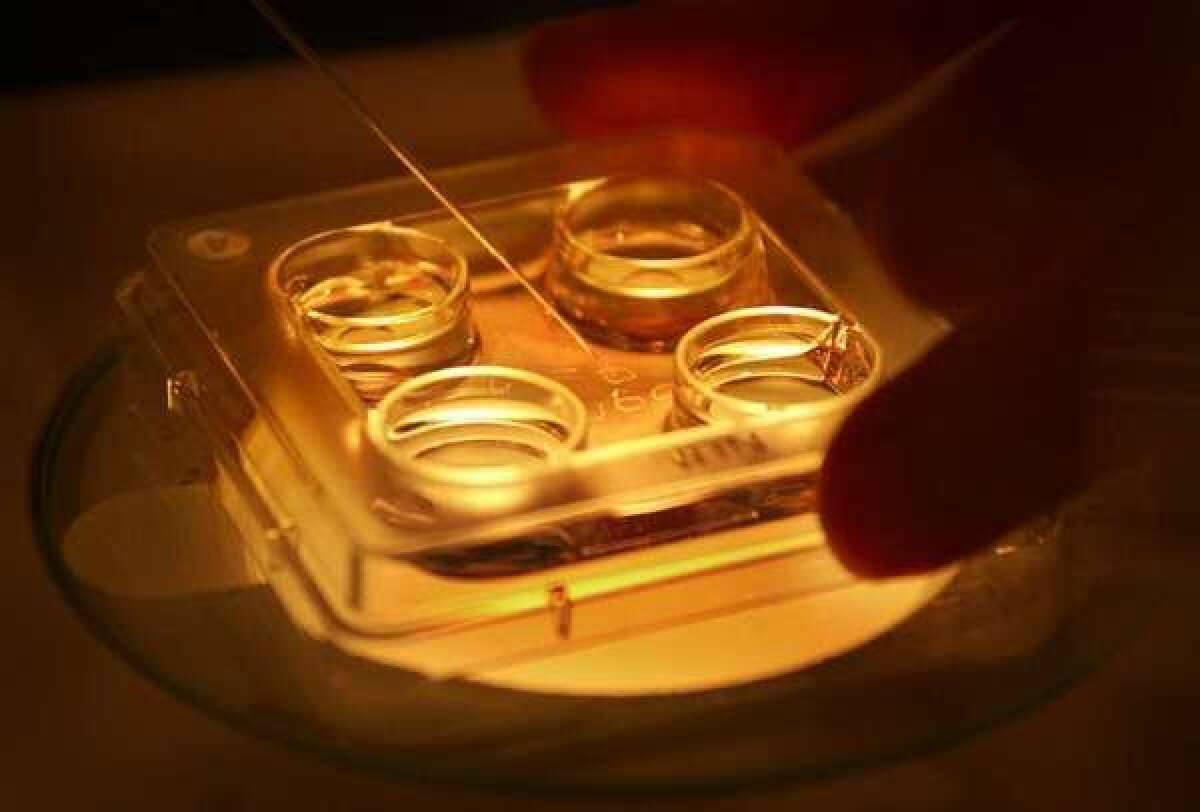

That inconvenient truth has helped spawn an industry of fertility specialists who’ve found ways to erase or push back the expiration date on an aging woman’s eggs. They can freeze a young woman’s eggs for later use in baby-making; they can boost an older woman’s chance of producing a good egg by stimulating the release of many; and they can use the egg -- and the nuclear DNA -- of a younger woman, fertilize it with sperm and implant the resulting embryo into the uterus of a prospective mother who’s run out the clock.

But David Sinclair, a Harvard Medical School scientist and entrepreneur who has pioneered research in anti-aging techniques, wonders whether fertility experts have missed something. In an article published Tuesday in the journal Cell Metabolism, Sinclair and coauthor Jonathan L. Tilly, a reproductive biologist at Massachusetts General Hospital, draw on advances across many fields to propose a way to rejuvenate aging human eggs.

Recent research has dispelled the long-held notion that a woman was born with all the eggs she’ll ever have, the authors write. Researchers have isolated ovarian stem cells -- precursor cells that give rise to eggs. Meanwhile, there’s mounting evidence that the problem with aging eggs lies in their mitochondria -- those ubiquitous little power plants that produce fuel for the cells’ every activity. In older eggs -- as in all cells as they age -- the population of mitochondria in a cell shrinks and the organelles themselves become a bit more bloated, inefficient and prone to error.

Why, ask Sinclair and Tilly, couldn’t we use a woman’s own adult ovarian stem cells to bump up mitochondrial function in her aging oocytes or eggs?

In the early 1990s, scientists tried a version of this that raised safety and ethical issues and was abandoned. They took the cytoplasm from a younger woman’s eggs (which would contain her mitochondria and its mitochondrial DNA) and they injected it into the cytoplasm of an older woman’s egg, which they then fertilized with sperm.

The youthful jump-start apparently supplied by the younger woman’s mitochondrial DNA appeared to invigorate the mitochondria in the older woman’s eggs: from 30 such attempts, 17 live babies were born, one with chromosomal abnormality. It was a remarkable rate of live births for women who had failed at several previous cycles of in vitro fertilization.

But the enthusiasm quickly waned, as research suggested that children with DNA from three people -- the egg donor, the older mother and the father -- might pay the price of short-circuiting evolution. In animals, experiments inducing such “heteroplasmy” resulted in late-onset metabolic abnormalities and poor cognitive function.

Perhaps, says Sinclair and his coauthor, ovarian stem cells, present and harvestable not just in embryonic females but in adult women of reproductive age, could supply women as they (and their eggs) grow older with the mitochondrial vigor they need to conceive later in life. Sinclair and his colleagues disclose that they have founded a start-up called OvaScience and filed for patent rights to techniques based on this research. They call the proposed technique Autologous Germline Mitochondrial Energy Transfer, or AUGMENT for short.

AUGMENT could allow some women to bypass the egg donor and reclaim her genetic link to her baby. By providing a “patient-matched source of these important energy-boosting organelles,” it could reduce miscarriages and chromosomal abnormalities in babies born to older women.

It could also generate a test-bed for exploring other means to rejuvenate aging eggs, wrote Sinclair and his coauthor. Using eggs that arise from ovarian stem cell lines, scientists could test the impact of chemical agents that could maintain or restore youth to a woman’s eggs as she gets older.

As the founder of the biotech firm Sirtris, now owned by GlaxoSmithKline, Sinclair has researched the anti-aging effects of the polyphenol resveratrol found in red wine, and of other agents that mimic the impact on dietary restriction in protecting cells from the ravages of aging.