National park on the moon at Apollo landing sites: A ‘loony’ idea?

Care to go for a hike in a national park? How about one on the moon? A bill introduced in Congress would protect U.S. Apollo lunar landing sites by making the detritus that astronauts left behind a part of the national park system.

It may sound like a loony proposal, but the Apollo Lunar Landing Legacy Act, or HR 2617, would seek to protect the spots where the Apollo missions left an artifact on the moon from 1969 to 1972.

The U.S. hasn’t sent a human to the moon in decades, and hasn’t announced any plans to return anytime soon. But the bill this week by Rep. Donna Edwards (D-Md.) and Rep. Eddie Bernice Johnson (D-Texas) comes as private companies move into space-faring enterprises and space tourism to the moon inches closer to reality.

“As commercial enterprises and foreign nations acquire the ability to land on the moon,” the bill’s authors wrote, “it is necessary to protect the Apollo lunar landing sites for posterity.”

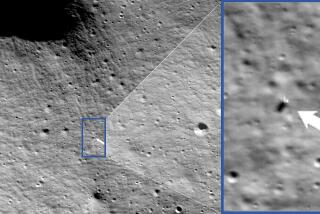

How awkward would it be if a sightseer accidentally scuffed out an Apollo 11 astronaut’s iconic bootprints in the Sea of Tranquility?

“It’s a good idea, because the moon’s environment is very fragile. Any disturbance of the soil there will last for millions of years. There’s a concern that private companies will want to transport tourists to these sites in the future,” David Paige, a planetary scientist at UCLA, said in an email.

The Interior secretary (whose department includes the National Park Service) would serve as administrator for the park, in partnership with NASA. The bill also requires that the Apollo 11 landing site be submitted to the United Nations to become a World Heritage Site within a year of the lunar park’s establishment.

That’s all well and good, except for one minor detail: By international agreement, the moon’s territory can’t be claimed. The artifacts themselves that were left behind – even by the Apollo 13 mission, which never landed because of a serious malfunction – are what would become part of a historical park.

It’s unclear on how this would affect the National Park Service, which usually operates on American territory, and how such artifacts could be protected without control of the land around them.

At the very least, Paige pointed out, it’s a useful mental exercise.

“Who owns the moon and who has the right to claim territory there – individuals, companies, governments?” Paige said. “I think it’s good that people are thinking about this subject.”