If you’re worried about prescription opioids, you should be really scared of fentanyl

The U.S. opioid crisis has passed a dubious milestone: Overdose deaths involving synthetic opioids like illicit fentanyl have surpassed deaths involving prescription opioids.

This switch occurred in 2016, according to data published Tuesday in the Journal of the American Medical Assn. And it seemed to happen pretty suddenly.

Data from the National Vital Statistics System show that there were 42,249 opioid-related overdose deaths in 2016. That includes 19,413 that involved synthetic opioids, 17,087 that involved prescription opioids and 15,469 that involved heroin. (In some cases, more than one type of drug was implicated in the death.)

That means synthetic opioids were a factor in 46% of all fatal opioid overdoses in 2016, compared with 40% for prescription opioids.

Just one year earlier, in 2015, 29% of all opioid-related overdose deaths involved a synthetic opioid (9,580 out of 33,091 deaths).

The year before that, in 2014, synthetic opioids played a role in just 19% of all opioid-related overdose deaths (5,544 out of 28,647 deaths).

Between 2010 and 2013, the percentage of fatal opioid overdoses that involved a synthetic opioid held relatively steady, ranging from 11% to 14%.

“We have been very focused on the threat of prescription opioid overdose deaths, and this paper shows us that we need to remain vigilant about the ever shifting nature of the crisis,” said Emily Einstein, a health science policy analyst at the National Institute on Drug Abuse and co-author of the JAMA study.

The drug that appears to be fueling the explosion in synthetic opioids is fentanyl, a narcotic that is “about 100 times more potent that morphine,” according to the Drug Enforcement Administration.

Medical versions of fentanyl have been in use since the 1960s, and about 6.5 million prescriptions for the drug were filled in 2015, the DEA says.

The problem with fentanyl is that it works too well.

“A very small amount of fentanyl can provide the same number of highs” as a larger amount of heroin or other street drugs, Einstein said.

“For an opioid user, it’s a very fast-onset high, and so it’s very rewarding,” she explained. “It’s also incredibly dangerous for the same reason. Its potency causes it to suppress respiration very quickly, and sometimes people will overdose with the needle still in their arm.”

Illicit fentanyl is not only being sold on its own. It’s also being combined with other street drugs, said Dr. Wilson Compton, NIDA’s deputy director and another of the study’s authors.

“We’re seeing fentynl being included in cocaine, we’re seeing it included in methamphetamine, we’re seeing it included in many classes of drugs sold on the street,” Compton said. “This toxic poison is now being seen both in fake pills as well as in the powders that are sold on the street, almost no matter what type of drugs people think they’re getting.”

It’s possible that illicit fentanyl and other synthetic opioids are doing even more damage than these new figures suggest, the researchers wrote in JAMA.

The National Vital Statistics System relies on information that coroners and medical examiners include on death certificates. But in 15% to 25% of fatal overdoses, the death certificate doesn’t specify the type of drug involved.

It’s also possible that synthetic opioids may have played a bigger role in previous years, but medical examiners didn’t see it then because there was less testing for these types of drugs at the time, they said.

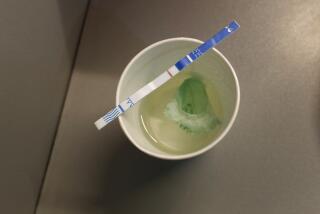

Regardless, the new figures make clear that the surge in synthetic opioids “poses substantial risks to individual and public health,” the researchers wrote. “Clinicians, first responders, and lay persons likely to respond to an overdose should be trained on synthetic opioid risks and equipped with multiple doses of naloxone,” a medication that can reverse the effects of an opioid overdose.

Follow me on Twitter @LATkarenkaplan and “like” Los Angeles Times Science & Health on Facebook.

MORE IN SCIENCE

Does exposure to animals during childhood buffer the body’s response to stress as adults?

These five healthy habits could extend your life by a dozen years or more, study says

Organs from drug overdose victims could save the lives of patients on transplant waiting list

UPDATES:

1:50 p.m.: This story has been updated with more information about illicit fentanyl and comments from the study authors.

This story was originally published at 11:05 a.m.