This common misuse of disabled parking permits could cost you $1,000

(Video by Mark Boster / Los Angeles Times)

Dressed in heavy boots and plain clothes, the Department of Motor Vehicles investigators lay in wait, ready to strike.

They skulked behind concrete slabs in the parking lot of the Glendale Galleria shopping center. Their quarry: customers suspected of illegally parking in spots reserved for the disabled.

“Hello, ma’am. I’m a DMV officer of the peace. We’re doing a compliance check,” one investigator said as he flashed his badge at a woman who parked her white Mercedes in one of the spots.

She was asked to produce her license, the placard and her registration.

But the placard didn’t belong to her.

The woman insisted it belonged to her husband.

But since it wasn’t hers, she was cited — and you could say she was apoplectic.

The TV camera crews that descended on the scene only made her more livid.

With tears welling in her eyes, she tried to walk away from the officers as she exclaimed: “Am I being arrested?”

Soon her husband and daughter arrived. They hurled expletives at the DMV investigators and then at the scrum of media.

“You portray our president as bad,” the daughter said as she tried to shield her face with a handbag before declaring the whole lot, well, jerks (but with another word).

The DMV — which has 200 sworn peace officers across the state — dispatched investigators to the shopping center Tuesday to nab people improperly using the disabled parking spots. These most desirable spots are close to the store entrances.

In the last three years, the state agency has conducted 270 of these enforcement operations and handed out about 2,000 citations. The number of citations issued has increased each year, according to data provided by the DMV.

DMV Commander Randy Vera said that it’s not uncommon for people who are caught to say that the disabled placard belongs to a spouse. But the person to whom the placard has been issued must be in the car when it’s parked in one of these spots. Vera said the problem is worse in areas where there aren’t many parking spaces and a lot of demand.

Last year lawmakers, believing there was rampant abuse, tried and failed to pass legislation toughening up regulation of the disability placards.

“The most frequent violators we get are those who are utilizing parking placards of a friend or a family member or a placard they found,” Vera said.

Sometimes people will buy them online, he added.

The citations can lead to fines that range from $250 to $1,000. On this day, the investigators stopped 280 people and found that 42 of them were using their placards fraudulently. They issued misdemeanor citations to these offenders.

The DMV recently conducted similar operations in Sacramento, and several years ago the department launched Operation Blue Zone.

They intended to root out drivers who improperly apply for disability parking placards. DMV investigators were on the lookout for people whose applications bore the same medical diagnoses, handwriting and doctor’s signatures.

Last year two lawmakers asked for an audit of the DMV’s application procedures. The results of that investigation are expected soon, according to the state auditor’s office.

Former Democratic Assemblyman Mike Gatto introduced legislation with former Republican Assemblyman Eric Linder that would have forced people to turn in placards after family members who had gotten them died. The legislation did not pass.

In the case of the Glendale operation, even those who were not cited because they had parked legally were often annoyed to be stopped.

One driver asked for the officers’ shield numbers and accused them of harassment. One woman wondered why people were photographing her before she put on her designer sunglasses, tousled her hair and used her Louis Vuitton bag as a shield.

But she was in the clear.

Other shoppers were less disturbed. After handing over her placard and identification, one woman who declined to give her name said: “I’m glad you guys are doing this because most people just get these placards from anywhere.”

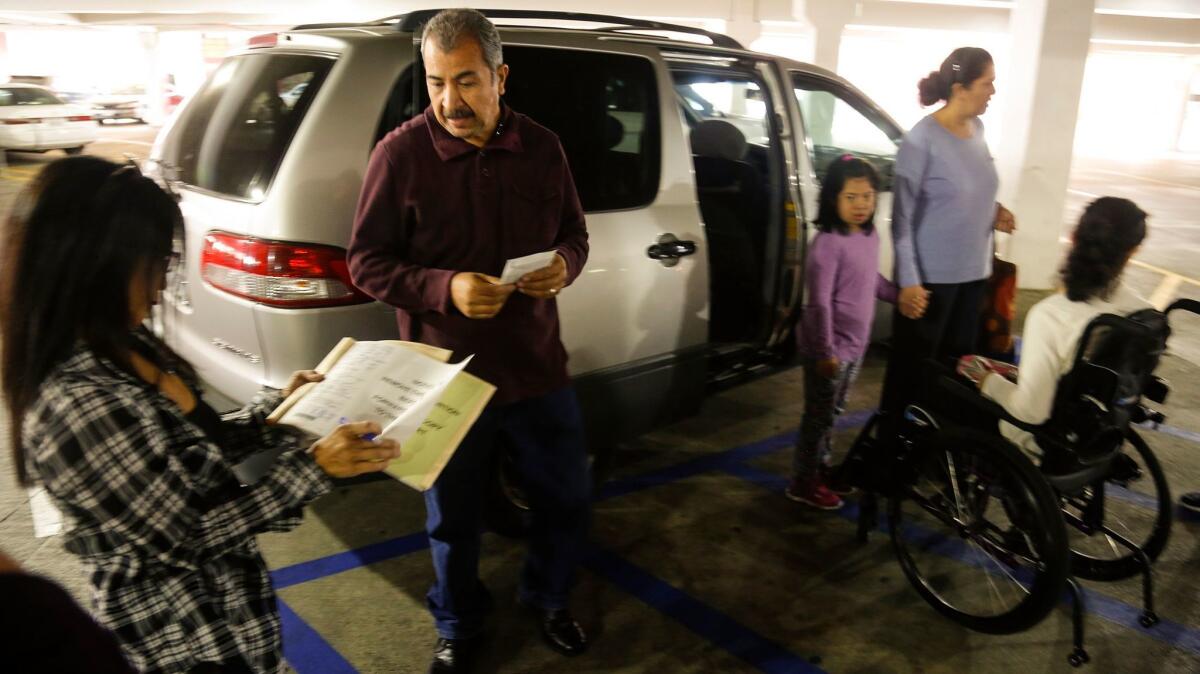

Hanna Shweyk said she often ferries around her octogenarian mother in their minivan. On days like this one when the parking lots are crowded with spring break shoppers, she’s lucky to find a parking spot for the disabled.

When all of these spots are taken, she’s forced to drop her mother off in front of the store and go hunting for parking. That means her mother is left alone, she said.

“Then I see people with no placards. I think this will teach them a lesson not to park here,” Shweyk said to a battery of cameras.

She turned away from the reporters and began to head to the shops, but stopped to ask with a smile: “Am I going to be on the nightly news?”

ALSO

L.A. might start citing motorists again for parking on city parkways

Hit-and-runs fell after California gave driver’s licenses to those here illegally, study finds

UPDATES:

4:10 p.m.: This article was updated with information about efforts to pass legislation tightening regulation of disabled parking placards.

This article was originally published at 5 a.m.