Angels outfielder Vernon Wells’ dad has a different frame of reference

Reporting from Keller, Texas — Angels pitcher Dan Haren wanted a special gift for his wife, Jessica. Something personal and out of the ordinary, but not gaudy or sappy.

So, he thought, how about a painting?

“It is different,” Haren decided, staring at the portrait he commissioned as he stood before his locker in the visiting clubhouse at Rangers Ballpark in Arlington earlier this month. “It’s a unique thing to give someone a painting of yourself, your family. Pictures are one thing, but a painting is really interesting.”

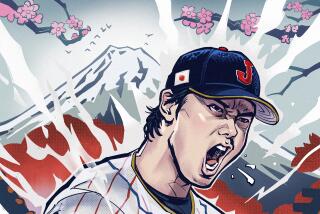

Photos: Portraits by Vernon Wells Jr.

It used to be that getting one’s own portrait was mainly reserved for presidents, members of the British royal family and ruthless Third World dictators. Now all you need is an idea and access to Vernon Wells Jr., father of the Angels outfielder with the same name.

Wells Jr. has been painting remarkably lifelike portraits of athletes for more than 30 years, producing nearly a thousand in all.

The Chicago White Sox, Toronto Blue Jays, Minnesota Twins and Texas Rangers ordered paintings to celebrate retirements or individual milestones such as no-hitters and most-valuable-player awards. Several New York Yankees teammates commissioned a massive montage to commemorate Mariano Rivera’s 500th save.

And then there are the players who order portraits for themselves.

“It’s cool to have a painting,” said the Angels’ Torii Hunter, who actually has three. “You go into a nice home or whatever, you see a painting of a grandfather . . . and you say, ‘Oh, this guy had to be someone special to have a painting.’ And that’s what I wanted in my home.”

The first painting Wells did of Hunter was homage to the outfielder’s spectacular catch in the 2002 All-Star game, when he climbed the wall to rob Barry Bonds of a home run. A likeness of Spider-Man, the nickname Sammy Sosa gave Hunter after the catch, appears in the foreground of the portrait.

“That’s my favorite one,” said Hunter, who hung his portraits in an entertainment room at his off-season home outside Dallas. “It’s memories. You look at it and you kind of remember the year or whatever.”

Wells’ portraits stand out for their intricate detail.

“Look at everything,” Hunter marveled. “The smile. The wrinkles in your face — if you’ve got wrinkles. If you’ve got a dimple, if you’ve got a mole. He has everything.”

Not bad for an artist who never took a formal art class and who discovered he had a marketable talent only by accident.

A standout wide receiver at Texas Christian University in the mid-1970s, Wells was invited to the NFL training camp of the Kansas City Chiefs. There, he doodled drawings of teammates during meetings to keep from falling asleep.

“Guys were like, ‘Man, guys will buy that stuff from you,’ ” Wells recalled.

After being cut by the Chiefs, Wells hooked on with the Calgary Stampeders of the Canadian Football League. A separated shoulder in his first exhibition game effectively ended his football career, but his time in Canada launched his art career when the team asked Wells to do a pen-and-ink drawing of its new helmet.

It was so good, the Stampeders put it on the cover of their media guide.

“So at that point I started doing stuff for players, primarily football,” Wells said. “And that’s really where it started.”

As he talks, Wells is sitting behind a massive drafting table in the second-floor studio of his home in a gated community just outside Fort Worth. It’s in a neighborhood of neat brick homes and well-maintained lawns not far from the exclusive Southlake neighborhood where his son lives.

To his left is a MacBook Pro. When the artist and a player agree on the concept for a portrait — Haren wanted to be depicted pitching for the four major league teams he has played for while his wife and two young children look on — Wells will scan in the photos, drop out the backgrounds and create different layouts. He then emails his client for approval.

His renderings are all done by hand yet are so realistic and detailed that it’s sometimes hard to tell them from the photographs.

“Part of my brain, I think, is Xerox,” said Wells, who charges between $6,000 and $20,000 a painting, depending largely on the size and complexity. “I do everything from photographs. And when I’m looking at the photograph, what I’m able to transfer from that photograph in my mind to the drawing board is the thing.

“It’s really about the seeing. Everybody thinks it’s the hands. It’s really not about that. It’s just seeing.”

When he’s seeing things right, the artist becomes an athlete again, settling into a groove that might keep him at his drawing table for stretches of 18 hours or more.

“I can’t do it 9 to 5,” he said. “It just doesn’t work that way for me.”

Like an athlete, Wells has learned to produce despite pain. The long hours hunched over a drawing board led to a ruptured disk in his neck that required surgery, a process that will soon be repeated. In the interim, he wears braces for his neck and back while he works.

His craft has also left him with an injured elbow, and he wears compression socks while painting to prevent blood clots.

Despite all that, Wells still looks as strong and fast as many of the star athletes in his portraits. At 56, his own playing days haven’t ended.

A two-sport star as a teenager, Wells gave up football long ago but still plays more than 100 baseball games a year — batting third and playing center field in various age-group leagues. Four years ago, he was inducted into the Dallas/Ft. Worth Adult Baseball Hall of Fame.

“If I had it to do over again, I would concentrate on baseball,” he said.

That’s the choice he nudged his son toward when young Vernon, a quarterback and baseball star, was ready to choose his career path — especially after the Toronto Blue Jays chose Vernon III with the fifth overall pick in the 1997 major league draft and offered him $1.8 million to sign.

“Vernon wanted to play college football,” his father said. “I told him, ‘If you’re going to choose football over baseball when baseball is willing to pay you $1.8 million now, then yeah, you need to go to college and learn some sense. Because that doesn’t make any sense.’”

Ten years later, the Blue Jays gave his son even more money, signing him to a seven-year, $126-million deal. When Wells was traded to the Angels in January with $81 million still left on the contract, he became the highest-paid player in the franchise’s 50-year history.

“It’s totally unreal. You know it’s going on, but it doesn’t make any sense,” Wells Jr. says of his son’s fortune, his voice hinting neither of jealousy nor joy. “He doesn’t live in the real world. His wife and kids don’t live in the real world.

“I’m happy for his success. It’s just our lives don’t run in the same circles.”

If they did run together, though, the elder Wells is certain he’d be quicker.

“He’s bigger, stronger,” the father said. “Not faster.”

Speed runs in the family.

“I would say my grandfather was the fastest,” said Wells III, who is currently on the disabled list because of a pulled groin muscle.

The late Wells Sr., who died in 2006, was a Texas state champion in the 100 and 220, though his son and grandson never heard him talk about it.

Humility and world-class speed weren’t the only things he passed on. His son and grandson also got his name, which has led to myriad problems.

“A line of three bad names,” the Angels’ Wells said with a smile.

“It gets a bit complicated,” acknowledged his father, who said people tend to assume he is Vernon Sr. and his son is Vernon Jr. “[People] know my name is Vernon. They know his is Vernon. It gets too bothersome to correct them.

“And now that my dad’s passed it’s not like we’re insulting him anymore.”

There is also a striking resemblance between father and son, but the truth is they’re not that close.

“I don’t see him much at all,” Wells Jr. said.

The Angels outfielder doesn’t offer much as an explanation. “No matter what walk of life or no matter what you have or have not accomplished in your life, family’s family,” he said. “There’s always going to be issues.”

But inside the sprawling home his hard work and inherited athletic talent brought him, his father’s presence is never more than a few feet away. And he’s proud of that.

“I have seven paintings,” Vernon III said. “They’re unbelievable. For him, being able to do what he does with paint, it’s remarkable.”

Photos: Portraits by Vernon Wells Jr.

More to Read

Get our high school sports newsletter

Prep Rally is devoted to the SoCal high school sports experience, bringing you scores, stories and a behind-the-scenes look at what makes prep sports so popular.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.