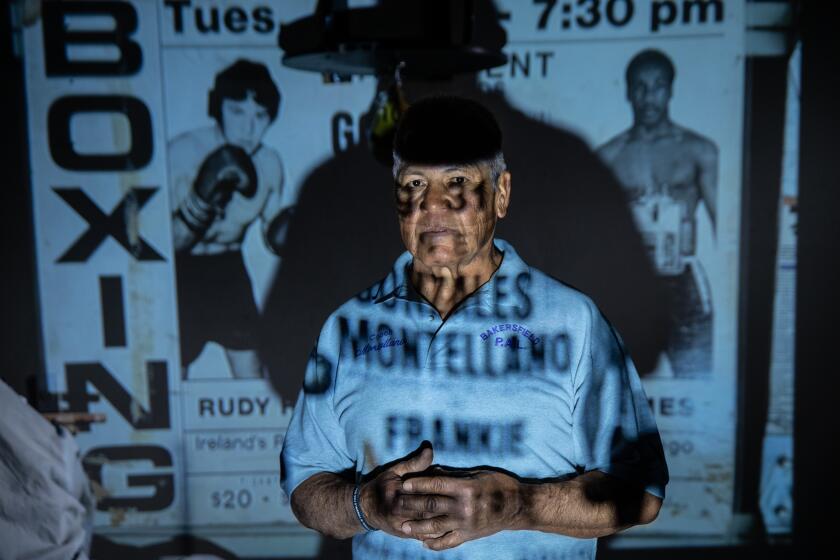

Once at the top of the fight game, Freddie Roach is now picking himself up from the canvas

A visit to Freddie Roach’s Wild Card Boxing Club in Hollywood used to mean a major fight was looming.

Manny Pacquiao trained there for 16 years while Roach was named trainer of the year seven times by directing him to a boxing-record eight division belts and the richest prizefight in history three years ago against Floyd Mayweather Jr.

Roach’s mother, Barbara, was a constant at Wild Card’s front desk, chiming in with Irish-accented quips to keep everyone, especially her son, on their toes.

Spotting a celebrity inside the gym, from Bob Dylan to Mark Wahlberg to Mickey Rourke, was routine, while finding an empty parking spot anywhere near the popular destination was like winning the lottery.

But all of them — Pacquiao, Mrs. Roach, the stars, even the parking attendant — are absent now as Roach, 58, glances around the empty downstairs gym he built for champions, and reflects.

“This is still my job, still what I love to do. I want to be here by 7 o’clock to work with the young pro kids. Then, at night, I help the amateurs,” said Roach, who has battled Parkinson’s disease throughout his career.

“I guess someday it will end [but] I think retirement might be a death penalty. When people retire, they get bored … so to get up at 6 in the morning and have something to do, it’s worthwhile. If I can help somebody, I’ll do the best job I can.”

It was one year ago Tuesday that Roach’s empire began to crumble.

He cornered Pacquiao in Australia for a welterweight title defense in a packed, 50,000-seat stadium that was intended to generate riches and a routine victory against a former Olympian from Down Under, Jeff Horn.

Instead, Pacquiao, then 38, showed more vulnerability than usual in absorbing some of Horn’s punches. And Horn employed rough tactics by grabbing Pacquiao in headlocks and hitting him in holds as the Aussie emerged with a controversial upset by decision.

“Manny was pissed off after the fight that Freddie only bitched after the fight about Horn resorting to unlawful tactics — not during the fight to a referee who could’ve stopped it,” longtime Pacquiao promoter Bob Arum said. “You know how Manny is. He’s not going to say all this, but he felt Freddie wasn’t the Freddie of before who tended to all those details.”

Earlier this year, Pacquiao opted to break from Roach, opening training to regain a secondary welterweight belt July 14 in Malaysia against champion Lucas Matthysse by relying on a training crew led by his close friend and former assistant trainer, “Buboy” Fernandez.

Pacquiao’s manager has said Fernandez running the corner will help him recruit more fighters as boxing’s popularity soars in the Philippines.

Reached there, Pacquiao explained to The Times, “I’m not saying I won’t come back to Freddie … just for this fight, I’m taking a rest. We can work again in the future if he can still train.

“I’m not mad. That’s why you haven’t heard from me commenting about Freddie. I’ll try to visit him after the fight if I have a chance.”

Roach never heard he was fired from Pacquiao. He only read that the others had assembled without him, the lack of explanation heightening the sadness.

“Being let go is part of the sport. Usually when a fighter loses a big fight, someone gets blamed and usually it’s the trainer,” Roach said. “But Manny has never blamed anyone but himself in his 16 years with me. Nobody was ever fired. We had wins and losses and he’d accept it, even when he got knocked out.”

After the pair roared to prominence with stirring Pacquiao routs of Marco Antonio Barrera, Oscar De La Hoya, Ricky Hatton and Miguel Cotto, Roach coached Pacquiao back from a knockout loss to rival Juan Manuel Marquez in solitary 2014 sessions in the Philippines that resulted in six knockdowns of Chris Algieri in Macao and the buzz necessary to finally force Mayweather into the ring with Pacquiao.

“The secret is that when we get to our training, I’m not the boss,” Pacquiao told The Times before pummeling Algieri. “You have to accept that’s part of boxing … to stay here [as champion] for long, to improve more, the trainer is the boss. I believe in Freddie; I’ve trusted him from the beginning.”

Yet, something changed that afternoon in Australia. Roach could see it in Pacquiao’s eyes in the post-fight locker room as the man Pacquiao previously called his “master” discussed the toll of trying to balance a heavy workload as a senator in the Philippines with title-fight preparation.

“‘You know, Manny, being a senator and being a world-champion boxer is very difficult … I know you’ve always multi-tasked, but you might want to think about doing one before the other,” Roach told Pacquiao.

The resulting silence struck Roach.

“Manny, are you mad at me?” Roach asked.

“He just smiled at me. That was it. And I haven’t spoken to Manny Pacquiao since.”

Roach sacrificed to train Pacquiao in the Philippines last year. Before the trainer departed, he left his mother following a third cancer diagnosis — this time in her pancreas after she conquered breast and uterine cancer.

“It was bad. My mother was so sick, she chose to not fight cancer this time and I said OK, but after 14 days of watching her get sicker and sicker, I wish I hadn’t said OK,” Roach said. “I should’ve said, ‘No, Ma, fight this one more time for me … .’ But I just couldn’t bring myself to do it, knowing how tough she was and thinking how bad it’d been that she’d been through the pain and the chemotherapy twice already.”

Upon his return from the Horn loss, Roach maintained an evening ritual of walking back into his dying mother’s home, comforting her in ways that brought tears to his close friend and assistant, Marie Spivey.

Roach spooned applesauce into his mother’s mouth nightly, gently let her sip from a water bottle and comforted her in conversation, even as delirium caused her to slip some and call her son by his father’s name, Paul.

“She was his conscience,” Spivey said of Roach’s mother. “He was there every day, telling his mom he loved her.”

Two days before Christmas, Barbara Roach died.

The fight work that fall had been marked by the farewell loss of Roach’s four-division champion Miguel Cotto and an inspired night as boxing coach for returning UFC legend Georges St-Pierre, who threw a Roach-taught left hook at middleweight champion Michael Bisping’s bad eye and then finished him by submission to recapture the belt at Madison Square Garden.

Finding cause to remain his vibrant self and retain his legendary work ethic in the face of his mother’s death “was difficult,” Roach said.

“But when I get here, I’m in a better place. I’ve had a bad back injury for the last few months, can barely tie my shoes and put my socks on, can’t pick things up. And there’s days if I have to bend down, I can’t. But by the time I get in the car and get here, the back warms up and I can hit the mitts with my prospect from the Mexican Olympic team … so that’s all I need.”

That fighter, Raul Curiel, is as Roach says just a prospect. The only active champion Roach has in camp is little-known super-featherweight Alberto Machado.

“A little disappointing, of course,” Roach says of residing outside his sport’s brightest lights.

“It’s fun to be famous … last Sunday I went out to my mailbox with a cup of coffee and a guy drives up and says, ‘You can’t hide behind that cup. I know who you are.’”

But recently, Roach’s best prospect, Lithuania’s Eimantas Stanionis, left him citing inattention and relocated to a Houston training camp.

And following an impressive March junior-welterweight title victory by Central California’s Jose Ramirez, the new champion took his belt and defected to Riverside to train under Robert Garcia for his first title defense.

“When fights get tougher, you need an overall team that has faith in you, can bring the best out of you and is motivated about you … Freddie has had so many champions in the past. I don’t know if I gave him the same excitement,” Ramirez said.

Roach was caught by surprise.

“Tough kid who was getting better, but … I lost him,” Roach said. “Robert Garcia didn’t steal him.”

Roach says he won’t poach anyone, either.

Last year he was in England to watch heavyweight champion Anthony Joshua defeat long-reigning champion Wladimir Klitschko.

“Joshua was thrilled to meet me and I was thrilled to meet him,” Roach said. “The kid’s a gentleman. He wrote me a letter after that and said, ‘How good could I be with Freddie Roach in my corner?’

“I thought, ‘Wow, that’s pretty nice.’ I’d like to tell him, ‘You’d be better than ever. I would love to train you some day,’ but I can’t answer this letter now because I don’t know if he’s a free agent.”

Roach doesn’t bind his fighters to contracts. He had a fight-by-fight deal with Pacquiao, taking whatever payment they agreed was fair.

So Roach is left to focus on coming fight dates that are far from pay-per-view consideration.

Gone are the cameras that followed his every move for the candid documentary series by Hollywood director Peter Berg. “On Freddie Roach” explored the trainer’s grinding work as he battles Parkinson’s.

A week after Pacquiao fights, the 27-year-old Machado (19-0, 16 KOs) defends his belt July 21 versus Ghana’s Rafael Mensah at Hard Rock Hotel in Las Vegas.

“It sounds like Freddie has time now,” Arum said. “He’s an excellent trainer, and if we have a fighter, we would certainly refer him to Freddie.”

The most important conversation Roach seeks is one with Pacquiao.

“Marriages haven’t lasted this long,” Roach said. “If Manny asked me to get on a jet and train him for free, I’d be the first one on the plane. We have a lot of history. Manny’s my friend. Money … I have enough.”

Pacquiao said if he defeats Matthysse, he’d like to return to fight in the U.S. against lightweight champion Vasiliy Lomachenko.

“Did you talk to Freddie?” Pacquiao asked. “When you talk to him again, can you please say hello? And please say thank you.”

Roach is carrying a gift for Pacquiao. On a recent flight, an elite pro darts player recognized the trainer and handed him a set of customized darts.

“I don’t play, but I’ll give these to Manny because he does. And I can’t wait to see his face when I do because he’ll know how much this means,” Roach said.

Twitter: @latimespugmire

More to Read

Get our high school sports newsletter

Prep Rally is devoted to the SoCal high school sports experience, bringing you scores, stories and a behind-the-scenes look at what makes prep sports so popular.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.