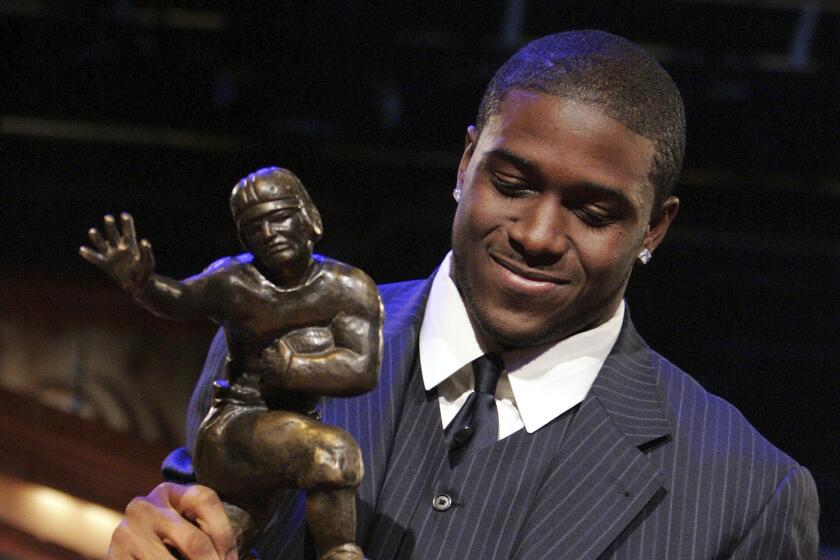

USC tailback Curtis McNeal is running to something better

Curtis McNeal was on his way out.

USC Coach Lane Kiffin, only a few weeks into his new job, was ready to dismiss the diminutive tailback known as “Moody.”

Generously listed at 5 feet 7, McNeal was a tough runner.

Hardened by a life growing up in projects, he was an even tougher sell.

The new staff had instituted new rules, new expectations.

“He was nowhere near buying in,” Kiffin said. “He was about gone.”

That was January 2010.

On Saturday, McNeal could be in the starting lineup when USC opens its season against Minnesota at the Coliseum.

The fourth-year junior’s turnaround ranks among Kiffin’s proudest achievements with the Trojans.

“It’s easy for people to always say ‘get rid of a guy’ if he screws up,” Kiffin said. “But with some kids, you have to realize what they’re going back to.”

Where McNeal came from was the Pueblo del Rio housing project in South Los Angeles, one of the oldest and largest in Southern California.

McNeal, 21, grew up there amid poverty, gang violence and drugs. He witnessed shootings and stabbings. He saw neighbors run over by cars.

“If that’s all you know,” he said, “it’s not really difficult because that’s your surroundings.”

McNeal moved into the project at age 6. His sister, Sonja, took him and two younger siblings into her home after their father suffered a debilitating stroke.

Sonja McNeal worked as a liaison for the Los Angeles Housing Authority. She raised seven children but kept Curtis fed, clothed and on a steady path.

“Even though it was public housing it was still like a safe haven,” she said. “I always knew where he was.”

Residents of the community, including gang members, also looked out for McNeal, who almost always had a basketball or football in his hands.

The night USC offered him a scholarship, McNeal said, he went out with friends. Not long afterward, his group encountered another. A fight erupted and McNeal was ready to join in.

But his friends pushed him away.

“They were like, ‘No, this is not for you,’” McNeal said. “They knew I had a better future. They were like, ‘You’re fine.’”

Competitor’s edge

Curtis McNeal wasn’t always known as Moody.

He was given the nickname while playing youth football for the L.A. Demos.

Not accustomed to the intensity or the volume of his coaches’ voices, McNeal withdrew and brooded. Other times he exploded.

“He wasn’t used to the yelling — and I pretty much yelled at him the most,” said Andre Harris, McNeal’s former youth coach and the father of USC defensive tackle DaJohn Harris. “We called him Moody Blues.”

McNeal played cornerback and running back. Fast enough to run past or away from tacklers, he often opted to run over them.

“Most guys avoid the hit,” he said. “I look for the hit.”

McNeal ran that way at Venice High, where his sister enrolled him in a magnet program so he would not attend school near home. Venice teammates shortened his moniker to Moody.

“He was an ornery, stubborn kid back then,” Venice Coach Angelo Gasca said, laughing. “But that’s part of what makes him what he is. And it’s given him his edge to overcome some of the things in his life.”

Stops and starts

McNeal scored 61 touchdowns as a running back, receiver, defensive back and kick returner in his final two seasons at Venice.

But skeptics told him he would never play for USC because of his size.

His struggles as a Trojan, however, have not been on the field.

He redshirted in 2008 and carried the ball only six times for 33 yards the next season. But he was happy to have contributed at all while waiting for his turn.

Then coach Pete Carroll left for the Seattle Seahawks. Kiffin and most of his staff arrived from Tennessee.

“It was totally different when they came in — a whole different structure,” McNeal said.

His performance during off-season workouts lagged. His attitude waned and he pondered leaving.

But a meeting in Kiffin’s office broke the ice.

“I just told him how I felt, he told me how he felt, and we just came to the same ground,” McNeal said. “I understood that I had to change my ways.”

McNeal bought in, but not completely. He was ruled academically ineligible a few days before last season’s opener, and spent a year making sure it would not happen again.

With senior Marc Tyler suspended, the 180-pound McNeal has emerged as a leader among the tailbacks.

“He’s got a high football IQ,” said D.J. Morgan, a redshirt freshman also competing for the starting role. “Learning from him, now I’m excited to come along.”

Better mood

As he prepared for his first big opportunity Saturday, McNeal said he was not thinking about crossing the goal line.

The sociology major was fixated on crossing a graduation stage next year. “I want to be able to show my sister that she was right to have so much faith in me,” he said.

Kiffin has put a program-wide moratorium on addressing McNeal as Moody. The rationale: He does not want him to embody the definition of the word.

“It still slips out with our coaches once in a while,” Kiffin deadpanned.

“The players,” McNeal said, grinning. “They still call me Moody.”

But it no longer fits.

A USC administrator recently remarked that the once-shy McNeal no longer drops his gaze in conversation.

During an interview, McNeal looked a reporter directly in the eyes.

“They always said I had a wall to put in front of people,” he said. “Now they’re saying the wall is getting lower and lower.”

And the young man emerging from behind it is rising higher and higher.

twitter.com/latimes.com

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.