Great Read: Dodgers’ Clayton Kershaw could finish on winning note yet

The baseball team at Highland Park High, just outside of Dallas, needed some fresh talent for the coming season.

It was the fall of 2002 when the coach wandered over to football practice, curious to see whether any freshmen might be athletic enough to play both sports.

The skill positions — quarterbacks, running backs and wide receivers — seemed his best bet until several players pointed him toward an offensive lineman.

“He was actually a dumpy kid,” coach Lew Kennedy recalled. “I wouldn’t say fat, but chubby.”

First impressions notwithstanding, the teenager had a decent arm, and Kennedy suspected that, with a little work, he might be able to help the team.

Just that quickly, Highland Park had itself a new pitcher.

::

Nearly a century has passed since baseball officials began cracking down on the deceptive spitball pitch and introduced a new ball — wound by machine rather than hand — to encourage more runs, thereby putting an end to the low-scoring dead-ball era.

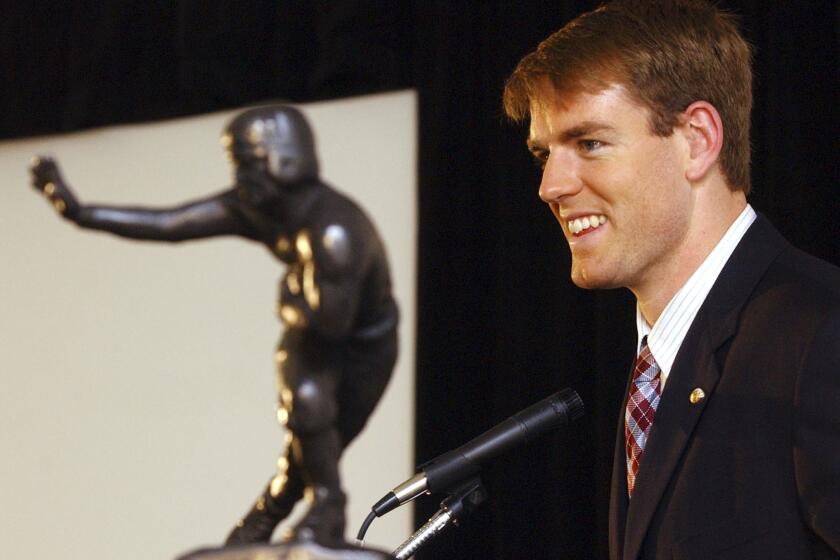

In all that time, only a few pitchers have put together a season like Clayton Kershaw had in 2014.

Twenty-one wins and a 1.77 earned-run average — the best numbers in either league — should bring him the third National League Cy Young Award of his career on Wednesday. Later in the week, he might also collect the trophy for most valuable player.

The Dodgers ace is 26 years old.

“Sometimes it just works out,” he said.

If Kershaw sounded a little understated, he quickly explained: “Hard to feel good with the way things ended.”

For all his gaudy statistics, the left-hander finished the season with yet another subpar performance in the playoffs, surrendering 11 earned runs in two losses to the St. Louis Cardinals. His postseason record now stands at 1-5 with a 5.12 ERA.

“I let one inning here and there get away from me,” he said. “It just seems to happen at the worst time.”

Which raises the question: Can a pitcher be considered truly great if he does not win in October?

Baseball historian John Thorn suggests it is a bit premature to assess the legacy of such a young athlete but acknowledges: “Some disappointments stick.”

If nothing else, Kershaw’s playoff struggles represent a curious anomaly.

::

The spin of a curveball creates subtle differences in airflow and surface pressure that move the pitch in the direction of the spin. This force is known as the Magnus effect, and it explains why Kershaw made the Highland Park varsity as a freshman.

“I was short and fat,” he recalled. “Definitely didn’t look the part.”

His curve was an equalizer, a trick that baffled larger, older opponents until he grew tall and lean as a junior. After that, he could muster the velocity to throw the fastball past hitters.

Watching this transformation, Kennedy tried to convince his young pitcher that brute strength wasn’t sufficient.

The coach wanted his protege to move the ball around the strike zone, close to the batter’s hands and then on the outside of the plate: “We worked on going in and out and having a plan.”

It remains unclear whether the advice took hold immediately. Thinking back, Kershaw said: “Honestly, I was just throwing harder and harder.”

His senior season became the stuff of folklore. He went 13-0 with a 0.77 ERA, averaging better than two strikeouts an inning. In the playoffs, he pitched a perfect game.

The growth spurt — and the velocity that came with it — changed the 6-foot-3 Kershaw’s outlook. As Kennedy put it, “He was a bulldog.”

Texas A&M offered him a scholarship at roughly the same time the Dodgers made him the seventh pick of the 2006 amateur draft, dangling a $2.3-million signing bonus. For a teenager growing up in a single-parent home, the decision was easy.

“It was a money thing,” Kershaw said. “Financially, college would have been a challenge for my mom and me.”

Arriving in Vero Beach, Fla., for rookie ball, he had no idea what to expect.

::

Each at-bat is a chess match.

Major leaguers can hit most any fastball if they know it’s coming, so pitchers try to keep them off balance with a variety of spins and speeds. A repertoire of two pitches — even good ones — often won’t cut it.

Kershaw learned this lesson in 2008 and 2009, when he made the jump from the minor leagues to the big time and lost as many games as he won.

“There were some struggles,” said Rick Honeycutt, the longtime Dodgers pitching coach. “So we tried to get a third pitch into the mix.”

That meant toying with the slider, which breaks less than the curve but travels faster. Kershaw flipped it around in the bullpen, getting a feel for the grip and spin.

As the 2010 season wore on, he tested it in games, but sparingly. “To throw it in big situations … that confidence takes a lot of practice,” he said.

The turning point came in 2011. Not only did the slider feel comfortable, but it became his go-to pitch when he needed a strike.

More of those chess matches started going Kershaw’s way as he streaked to a 21-5 record. The baseball writers who vote for the best pitchers in each league handed him his first Cy Young Award that season.

“I had one more pitch to put in the back of the batter’s mind,” he said. “That made it easier.”

::

A.J. Ellis knows the drill by heart.

“Everything’s dictated by the clock,” the Dodgers catcher said. “All the boxes need to be checked.”

Over the years, Kershaw’s desire for control has morphed into a pregame routine that borders on ritual. It begins two hours before the first pitch with a meeting in which he, Honeycutt and Ellis trade notes on opposing hitters.

With 30 minutes to go, Ellis knows that he must be standing in the outfield for seven to eight minutes of warmup tosses with Kershaw. Then they head to the bullpen.

“He’s going to throw the exact same 34 pitches,” Ellis said. “In the exact same order.”

The catcher remains standing for the first three fastballs. After that, he gets into his squat for three more fastballs down the middle and three to either side. Three changeups come next, followed by a fastball inside, three curves, another inside fastball and three sliders.

Four fastballs — two inside, two outside — lead to the final pitches: two change-ups outside, a fastball and two curves, another fastball inside, two sliders and the final two fastballs, inside and outside.

“Let’s say he’s not throwing the slider the way he should,” Ellis says. “He’s not going to deviate and throw extra sliders.”

All the while, Kershaw keeps an eye on the time, aiming to finish by the national anthem. He then takes his customary spot in the middle of the dugout, with Ellis and Honeycutt by his side.

Some might call it superstition, but Kershaw has a different explanation.

“It’s just peace of mind,” he said. “You find what works.”

::

Tom House pitched eight years in the major leagues, spanning more than 535 innings and 2,200 batters. Yet the former Atlanta Brave is still trying to understand the art of throwing a ball 60 feet 6 inches.

This quest has led him to employ kinematic sequencing and mechanical variables, a set of quantifiable parameters. At the pitching school he runs in Southern California, House has analyzed video of hundreds of major league pitchers and sees two things that stand out about Kershaw.

The first involves something that House refers to as “tunnel” — Kershaw’s pitches all start out looking similar to the batter.

“Like they’re going down a PVC pipe for the first four to six feet,” House said. “Everything looks like a fastball and becomes something different later.”

The delayed movement on the slider, for instance, gives batters scant time to adjust. They must adapt to changes in direction and, just as important, velocity.

Which leads to Kershaw’s second particular talent.

His fastball is generally in the 92- to 95-mph range, but his curveball is much slower. House says if the difference in speed is 12 mph or greater, it will usually trick batters into swinging too early and flailing at air.

House has timed the difference between Kershaw’s fastball and breaking ball at 18 mph or more.

“Even if hitters know it’s coming, the brain can’t react,” he says. “It’s almost impossible to hit.”

::

Don’t expect Matt Carpenter to give up any secrets.

The St. Louis Cardinals infielder has a .307 batting average against Kershaw in the playoffs and has hurt the Dodgers with key hits in each of the last two postseasons.

“You’re just trying to fight,” he said vaguely. “He doesn’t make a lot of mistakes, so when you get one, you’ve got to take advantage.”

Kershaw’s playoff struggles have given rise to numerous theories.

Maybe his arm wears out at season’s end. Maybe the Cardinals have figured him out — when they get men on base, he seems to resort to his fastball.

Whatever the reason, the losses have stung.

“People don’t care about what you’ve done in the past. It’s ‘What have you done for me lately?’” Kershaw said. “People turn on you really fast, and I know that.”

Thorn, the historian, points out that former Dodgers great Sandy Koufax had a 4-3 postseason record and ended his career with a 6-0 loss in the 1966 World Series. As for Kershaw’s legacy, he suggests giving it some time.

“Distance is a good thing,” he said. “It provides perspective.”

After a few weeks away from the game, Kershaw would rather talk about starting his off-season workouts — all the sweat that goes into preparing for next spring.

There is no hint of panic in his voice. No tweak to his pitching motion or strategic shift is in the offing.

“There’s nothing to do differently,” he said. “Just keep pitching.”

Twitter: @LATimesWharton

More to Read

Get our high school sports newsletter

Prep Rally is devoted to the SoCal high school sports experience, bringing you scores, stories and a behind-the-scenes look at what makes prep sports so popular.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.