LaRon Armstead found salvation in basketball

LaRon Armstead is a former college athlete, 6 feet 5 inches tall, 23 years old and physically imposing. Yet, standing outside Holmes Elementary in South Los Angeles, he is actually shivering — and not from the cold.

He has returned to his old neighborhood for the first time in 10 years because an acquaintance has asked to see his childhood haunts. But he can’t help himself. His body is physically reacting.

“It’s scary,” he says, voice trembling. “It reminds me of who I was and who I was on track to be.”

Armstead, the sixth of 13 children, was raised in the Pueblo Del Rio housing project, a place he says was shrouded by hopelessness, where drugs were sold at all hours and gunshots were part of the normal cacophony of life. His mother, father and oldest brother were affiliated with gangs.

A buddy of his had brought drugs to this school. When he was 9.

A little earlier, while being driven down 53rd Street, Armstead is so uncomfortable that he insists the car’s windows be rolled all the way up.

He sees the food stand where he bought tacos at midnight. He sees the park where he and his friends went to fight in the middle of the night.

“We had no curfew,” he says. “The later you stayed out, the better it was. You could see people selling drugs. You could see all the things you wanted to do.”

Armstead recently went to visit his oldest brother, who is in prison, for the first time in about 10 years. He was told that four of his former friends, boys he hung out with in grade school and junior high, are also incarcerated.

“I feel guilty,” Armstead says, “that I made it out and others won’t live anywhere else.”

How did he do it?

It started with a listing on a bulletin board.

::

A few months ago, in a ballroom at the historic Millennium Biltmore Hotel, civic leaders and local business titans gathered with a few Hollywood personalities for the Salvation Army’s annual holiday fundraiser.

All had dined on turkey and pumpkin pie. Now it was time to listen to the night’s keynote speaker, a young man who, as he strode purposefully toward the podium to the sound of polite applause, few in the room recognized.

Over the next 12 minutes, LaRon Armstead told his life’s story in a way they would never forget, starting with his background as a middle school drug dealer.

“While other kids were going to Disneyland, camping trips, having fun, me and my friend were dealing,” he said.

As a seventh-grader, selling marijuana had put hundreds of dollars in his pocket, and Armstead spoke about his reputation as a gangbanger and fighter — and of his turning point: the day a friend spotted a notice promoting a three-on-three basketball tournament and signed Armstead up to be part of the team.

He was not a natural athlete. He recalls his team scoring one basket the entire tournament. But it didn’t matter. He had fun and found encouragement from a couple of the men who were organizers of the event. Over time, they helped him completely change his path.

Within a year, a new Salvation Army community center was Armstead’s second home. He played basketball in the gymnasium and was given chores. The people there fed him, counseled him and mentored him.

Other family members stayed with the gang — the Pueblo Bishop Bloods — but LaRon managed to leave. “After school, I went a different way,” he says. “Growing up in it, they couldn’t say anything to me. I was doing something good for me.”

His grades soared and his dreams blossomed. He recalls that when he graduated from middle school, “I didn’t know how big an accomplishment it was until I saw my mother cry.”

However, there were still plenty of challenges to overcome. When he was a sophomore at Fremont High, his family was evicted from their residence and moved into a small home owned by his grandparents. There were 15 people sleeping in two bedrooms. Food was scarce, the showers were cold, and at times there was no electricity. He used his backpack as a pillow and slept on the floor — but he was never tempted to go back to gang life. Not even for the money.

“That’s not a life anyone with any sense would want to go back to,” he says. “I was changed.”

He concluded by telling his rapt audience: “I do not expect a handout. I will continue to work for what I need to accomplish and see the possibilities in every obstacle.”

When he finished, there was a long standing ovation.

::

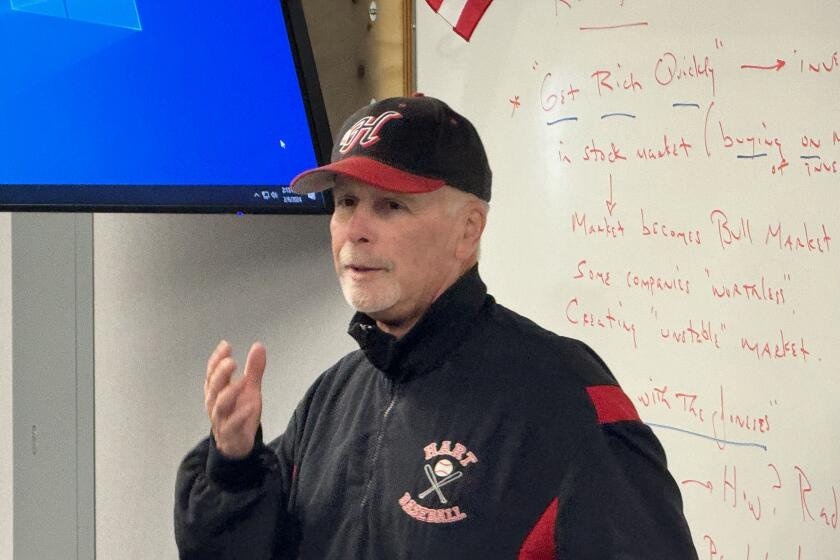

Emailed a copy of Armstead’s speech, Don Larson marvels at its eloquence.

Larson was a program director at the community center when Armstead first showed up. He recalls that the young man couldn’t put two sentences together on a piece of paper. But he knew Armstead was smart. He had to be to survive the way he was on the street.

“I explained to him that if he was smart enough to hang out with the adults, he was smart enough to get good grades,” Larson says during a phone interview from San Francisco, where he now resides. “He flipped on the switch in school and in basketball.”

Andre Patterson, another man who helped guide Armstead, still works at the community center, which is located at 76th Place and Central Avenue in South Los Angeles. Written on a wall outside the center are the words “Where hope and healing begin.”

“Every time I look at him,” Patterson says of Armstead, “I just can’t believe he became the person he became. He is hope.”

Sitting on the floor off a hallway during a recent visit, Armstead emotionally recalled the center as “home to me, a home that kept me away from all the [bad] things in L.A.” The people there, he says, “taught me how to respect, how to play team ball, how to stay positive when things are going down, how to face adversity, how not to be so angry when things aren’t going your way.”

Armstead became an All-City basketball player who worked his way into the opportunity of a lifetime: He was offered a basketball scholarship to attend Loyola Marymount.

“Coming from where I grew up and being told every day, ‘You’re not going to make it; what’s the use?’ It’s a big turning point,” he said at the time.

Over four years at LMU, Armstead played in 109 games, averaging 6.2 points and 2.8 rebounds. As a senior, he became a starter for a team that defeated UCLA on its way to 21 wins.

Max Good, LMU’s coach, says of Armstead, “I’ve been coaching 40 years, and I don’t know if I’ve been around a more unique, driven person.”

Near the end of Armstead’s senior year at LMU, his mother, Linda Million, came to watch him play in college for the first time. A week later, she died in her sleep.

“It was so hard being that she passed during my senior season,” Armstead says. “I was the first person in my family to go to college and also graduate. I was sad, because she did not get to see me graduate and walk the stage, but I know she was with me in spirit.”

::

Last May, Armstead graduated with a bachelor’s degree in sociology. A career in professional basketball overseas beckoned, but he turned down the opportunity in order to stay at LMU and pursue a master’s degree in education.

“My brain is my strongest weapon, not my body,” he says by way of explanation.

Armstead gives motivational speeches at schools and YMCAs across Southern California. He has a part-time job working in the human resources department at LMU, serves as a graduate assistant for the LMU basketball team and also volunteers as a coach for a middle school basketball team, imparting to his players that “just because people tell them they can’t make it because of who they are and what they are … they should not listen to the negatives but keep hope.”

He wants to go to law school and perhaps become a sports agent or work in sports management. Most of all, he is motivated to help impressionable young people.

Even with his full schedule, he pauses about once a week for the solitude of a bench located on a bluff at the top of the Loyola Marymount campus. From there, he can see the surf of the Pacific Ocean, the high-rise buildings of Century City and the iconic Hollywood sign staring out from the Santa Monica Mountains.

“When I was at Holmes Elementary School, we could see the Hollywood sign out of our window,” he says. “We’d go upstairs to a hallway and we’d look out and say, ‘That’s where we want to be.’

“It’s strange how I’ve been on two different sides of L.A., and how my life has progressed. It makes me appreciate everything in life, seeing the whole city and where I’ve come from.

“It makes me feel I can do anything in the world.”

More to Read

Get our high school sports newsletter

Prep Rally is devoted to the SoCal high school sports experience, bringing you scores, stories and a behind-the-scenes look at what makes prep sports so popular.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.