Cory Hahn is still part of a team

From Tempe, Ariz. -- The coach once helped carry his son from tee ball to the top of the high school baseball world, never missing a game, cheering every moment, from midnight batting practice to driveway bullpen sessions to championship glory.

Today, the coach gently places his son over his shoulder and carries him from his wheelchair to the front seat of his dusty truck.

“We were never much for hugging,” Dale Hahn says. “But now I get to hug my son all the time.”

The coach once pushed the son to become California’s Mr. Baseball, working on his swing, inspiring his hustle and watching him become a powerful outfielder with speed, smarts, a full scholarship to Arizona State and a major league future.

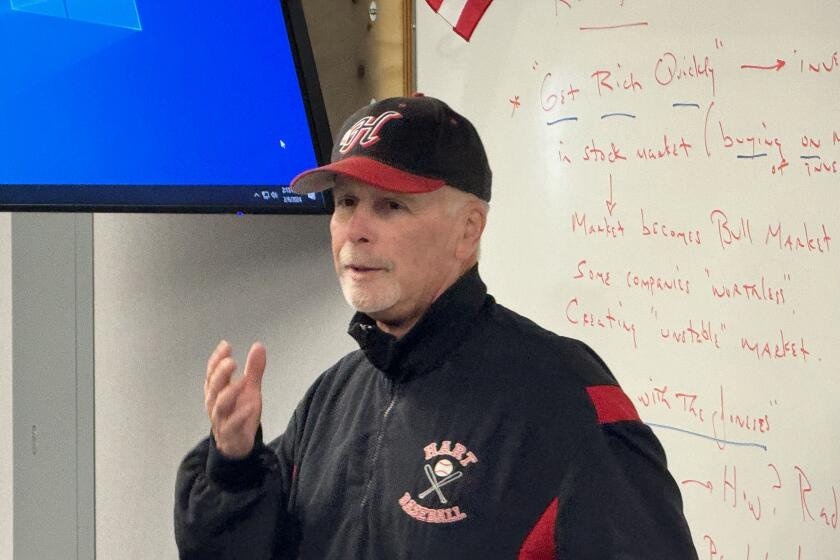

Now, the coach pushes the son’s wheelchair across busy streets and over large bumps to a college economics class.

“There were times I would wonder, what’s better, being dead or being like this?” Cory Hahn says. “But then I look up and see my dad and think, if he can do it, I can do it.”

It has been a year since this former Santa Ana Mater Dei High baseball star broke his neck diving into second base in his third collegiate game, shattering the life of the Southland’s brightest baseball star into tiny dark pieces.

Yet while everything has changed, nothing has changed.

Cory Hahn is a C5 quadriplegic, paralyzed from the chest down. He has limited use of his hands and arms. The kid who once led his team to a CIF championship by pitching five perfect innings, making an over-the-shoulder catch and hitting a long home run now battles to eat hamburgers, wash his hair and wheel to class.

“My goals don’t take days anymore, they take weeks, they take months,” he says.

But, as always, Cory is able to stretch toward those goals from the broad shoulders of the balding guy he calls Pops. The man who always urged him to give full effort by “Spilling your bucket” has met this challenge by overturning his life.

After spending years as his son’s baseball coach, Dale Hahn has quit his job as a sales rep to become his son’s life coach.

When Cory moved back to the Arizona State campus in January to continue his studies, Dale went with him. While Cory moved into a rental home with three teammates, Dale moved into an extended-stay hotel down the street.

Cory awakens every morning to the sound of his father’s key in his bedroom door. Dale shows up at 7 a.m., flicks on the lights, turns on the television, maybe turns on the space heater, and then pulls his son out of bed to begin their day.

Together they dress and shower and prepare Cory, with each day painstakingly bringing a tad more separation for the fiercely independent son. Just the other day, they celebrated that Cory was using his once-lifeless hands to wash his own hair.

“We live for the little victories,” Cory says. “We’re a team.”

Together they drive to campus in Dale’s truck, where they go from a street parking spot to Cory’s first class, with Cory wheeling himself most of the way. It is a process that makes his shoulders ache and has turned his hands into giant calluses, but he refuses to use a power chair or wheelchair gloves, staring down his new life as he once stared down 90-mph cutting fastballs.

“I see all these college kids running and skating across campus, and then I see Cory just chugging along in his chair, the world moving past him,” Dale says. “I feel really bad for him … and I am so, so proud of him.”

After classes, together they go to lunch, with Cory able to feed himself only after countless days of practicing with his dad. Their efforts were fueled from the embarrassment Cory said he felt when, eating lunch for the first time with friends, he realized they would have to feed him.

“That devastated me,” Cory recalls. “I told my dad, we’ve got to figure this out, and it was really messy, but we did it.”

After lunch, they go to a gym for therapy, and then his father might drop him off at a Sun Devils baseball practice or game before taking him home for the night. Cory will hang out with friends until about 11 p.m., at which point his father returns to his room to lay him into bed and put the television on a timer and slip out with a simple, “Good night, buddy.”

“When you’re a dad, you’re a dad forever,” Dale says.

A year ago, forever was about preparing his son to become a millionaire baseball player. Today, forever is about helping him put on his shirt. But it’s the same forever, the same commitment, the same, “Dad.”

The only thing the Hahns do separately, it seems, is mourn.

Shortly after the accident, Cory hysterically cried through the middle of the night, fighting feelings of terror that he still occasionally feels today.

“I was terrified about the rest of my life,” Cory remembers.

At the same time, outside the hospital, walking the long blocks between his hotel and his paralyzed son, Dale would be openly screaming with the same fear.

“I was just mad at the world, shouting all kinds of stuff; I’m sure people around me thought I was crazy,” Dale remembers.

Separately, they have wept, but together, they have grown stronger, this evil break in a vertebra being challenged by the goodness of a bond between a father and a son.

“You’re in awe of them, huh?” says Chris Hahn, Cory’s mother, who remains in their Corona home with their other son, Jason. “Stand in line.”

::

Yeah, Dale Hahn was that father.

He was the guy who coached his son’s youth league teams, all of them, every day, the guy who showed up at the park every spring with a goofy smile and buckets of balls.

He is that guy who keeps the flexible sales job so he could spend more time teaching the neighbor kids how to swing a bat. He is that guy who drives old cars and dresses in workout clothes and lives in a modest house because he spends most of his time and money on watching his children run around a diamond.

“Being a dad was clearly the most important thing to him,” Chris says. “His job was always, like, fourth on the list.”

Dale would play catch with young Cory between their driveway and a driveway across the street because the slope of the driveways replicated a pitching mound. Dale would throw soft-toss batting practice to Cory in a net in the backyard, or, on rainy days, in a net in the garage. Once, after a particularly bad game at Mater Dei, Cory took midnight hacks off his father into a portable net next to their community tennis courts. When Cory joined the Mater Dei team, Dale was no longer his coach, but he still coached him, watching games from down the third-base line, sharing tips with his son afterward.

“Not once has my father pushed me to anything but being happy,” Cory says. “I wanted him working on my game because he was the best baseball man I knew.”

Dale was the kind of father who, with Chris, agreed to host a giant, raucous party for the Mater Dei baseball team and fans after the Monarchs defeated Dana Hills to win the 2010 Southern Section championship.

Dale was the kind of father who supported his son when he turned down as much as $300,000 from the San Diego Padres so he could attend Arizona State and spend three years growing his game.

And Dale was the kind of father who, upon hearing that Cory had worked his way into the Sun Devils starting lineup for the opening of his freshman season against New Mexico, left his home at 5 a.m. the next day to drive to Phoenix to watch him for the rest of the series.

So Dale was there when, in the first inning of the Sunday game, his son took off from first base on the back end of a double steal and did something that Dale had almost never seen him do.

“I can count on one hand the number of times I had ever slid head-first,” Cory says. “I never advised it, never practiced it, never really did it until then … it was just a reaction.”

It was a reaction that changed his life forever, as he slid directly into the second baseman’s leg, breaking his neck with such force that he actually heard it snap.

“I was tilted on to my left side, and I could see the ball rolling into the outfield, and I knew I had to get up and run to third,” Cory remembers. “I was like, ‘Dude, get up!’ … But I couldn’t do it. … I couldn’t move.”

As the ambulance arrived, he remembers asking Sun Devils Coach Tim Esmay where he was.

“You’re on second base,” Esmay said. “You were safe.”

“Damn right I was safe,” Cory replied.

Damn right I was safe is a saying that his teammates now wear on bracelets in his honor. It represents the perfect blend of bravado and belief that both men have used throughout this fight. And when that has failed, they have bargained.

Says Cory: “I told God I would do anything he wanted if he would just let me walk out of that bed.”

Says Dale: “I told God I would do anything he wanted if I could take my son’s place in that bed.”

Cory believes he will walk again. His family believes he will walk again. His parents are so sure of it, when an unknown doctor who did not perform the surgery tried to tell them otherwise, they walked away before he could finish his sentence.

“Maybe Cory can’t do the same stuff, but he’s the same kid, and he’s got the same attitude,” said Phil Lopez, Cory’s closest friend. “If you test his strength he’s only going to get stronger.”

The same can be said about Dale, who says he made the decision to quit his job and work with Cory full time because it just made sense. They were using the insurance from Chris’ job as a sales manager for a uniform company, so she couldn’t quit.

“Dale has just always done a tremendous job with Cory,” Chris says. “I did it for three days and I was so exhausted, I honestly don’t know how long I could have done it.”

How much longer can Dale do it? They are reluctant to hire a caretaker while Cory is still adjusting to his college environment, so Dale will stay there at least for this semester. They are surviving financially with help from a couple of recent fundraisers and an ongoing Cory Hahn Fund that can be accessed from the Mater Dei website. But what next? They have no idea. Nobody has any idea.

At this point, the only thing certain is the devotion in their weary eyes as they look at each other from across a table, Cory Hahn stuck in a chair, Dale Hahn trying like hell to give him wings.

“That’s my guy right there,” says the son, nodding.

“‘Yeah,” says the coach softly, nodding back. “I’m your guy.”

More to Read

Get our high school sports newsletter

Prep Rally is devoted to the SoCal high school sports experience, bringing you scores, stories and a behind-the-scenes look at what makes prep sports so popular.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.