Amir Khan looks for success in the ring, acceptance outside it

Amir Khan of England will be fighting in Las Vegas on Saturday night, but not simply to defend his World Boxing Assn. junior-welterweight belt.

He’s in the U.S. to also test his faith that a Muslim athlete of Pakistani heritage can win the hearts of American fans.

“Politics is a lot different than sport,” Khan said last week as he hurried out of his Hollywood apartment complex to attend Friday prayers at a Los Angeles mosque. “I can break barriers with my skills and change things about the way people think of Muslims.

“We’re all equal, we’re all trying to succeed and we should all get along. That’s what sport does: brings people together.”

His optimism is rooted in his youth — on Wednesday, he turned 24 — and in his success. At 17 he became an overnight sensation after winning the silver medal at the 2004 Athens Olympics and today is a world champion in the talent-rich, 140-pound division.

Yet he knows firsthand how in Britain, as in the U.S., the fears that come with the war on terror can be triggered in an instant, and have occasionally made him a target of vitriol just because he is Muslim.

As one online critic wrote recently on a British boxing site: “We constantly have to fear Muslims. … It’s always Muslims that blow our loved one[s] up. Why on earth wouldn’t we hate a guy that supports the same faith as those guys?”

Khan, who in an interview last year said if he were white “maybe I’d have been a superstar in Britain,” says he no longer believes that.

“You get past that,” he said of the rants directed at him online and from some fight fans when he’s in the ring. “You want to prove those people wrong.”

He knows winning can help do that. To that end, Khan (23-1, 17 knockouts) successfully defended his belt in his U.S. debut in May, scoring a technical knockout of Brooklyn’s Paulie Malignaggi in New York. On Saturday he will face hard-punching Argentine Marcos Maidana (29-1, 27 KOs).

Khan is eager to own the spotlight here.

“I’m the youngest British fighter ever to defend a title in America,” he said. “I want to be known all around the world. To do that, you have to fight everywhere and prove yourself.”

At morning prayers last week, Khan arrived late and kneeled outside the mosque in the overflow crowd of worshippers, some of whom were aware a rising sports star was in their midst.

“A lot of bad things are happening when a lot of good things should be” the focus, said John Shiakh, 48, a Bangladesh native who prayed with the boxer at the mosque that day. “So it’s nice to have someone like him from our community promoting peace and how we really are.”

Time spent with Khan offered a glimpse of that. Being in the U.S. is also quality family time. On one recent day, Khan’s father, Shah, and his mother, Falak, are with him. As Falak irons her son’s dress clothes, Amir’s brother, Haroon, 19, chats on Skype with his two sisters in England — one of whom is pregnant.

Khan heads to the kitchen but avoids the Frosted Flakes atop the refrigerator. Instead, he devours a breakfast of eggs, beans, tomatoes, mackerel and coffee. He tells of the first time he walked into a boxing gym in his hometown of Bolton, England. He was 8 and his parents were looking to provide an outlet for his hyperactive behavior.

“I had something to divert my energy and I was willing to learn,” Khan said. “I loved boxing — hitting the bag, the sweaty smell, even being punched.”

As he talks, it is hard to miss the plaque nearby, given to him by a friend. It reads, “May Allah give you the strength to succeed in all that you do.”

“Amir’s religion is his religion,” said Shah Khan, who moved to Britain from Pakistan as a boy. “He stands behind it 100%. We, as Muslims, have had a lot of negativity in this country, but everybody’s not the same and Islam doesn’t tell you to kill people. I would hope people could believe that and point to someone like Amir and say, ‘Look what he’s doing.’ More guys like Amir can bring people together.

“Amir sets himself goals you don’t think are possible and he achieves them. Now he wants to be the best in his sport, a legend as a sportsman in this country.”

Two years ago, Amir Khan looked done after losing at home to an unknown, Colombia’s Breidis Prescott, who flattened Khan twice in a fight that lasted 54 seconds. Khan fired his trainer and hired Freddie Roach, the renowned teacher who has guided the ascent of Manny Pacquiao.

When Khan became world junior-welterweight champion last year, he hit a crossroads: fight in larger arenas for larger purses in Britain and the rest of Europe or head to the U.S.

Against Maidana, Khan will be relying on his ring speed but perhaps even more on his training. He spent a lot of time sparring with Pacquiao, the best pound-for-pound boxer in the world.

“He’s the only guy I know who can keep up with Pacquiao,” Roach said. “He’s the best listener I’ve ever had. Maidana was third on my list of the three guys they presented to him to fight, but Amir said, ‘I want the best one first.’”

Khan worked hard to recover his career, more than willing to bend with the ever-shifting training camps from the Philippines to Texas to Hollywood to accommodate Roach’s work with Pacquiao — “never complained once,” Roach said.

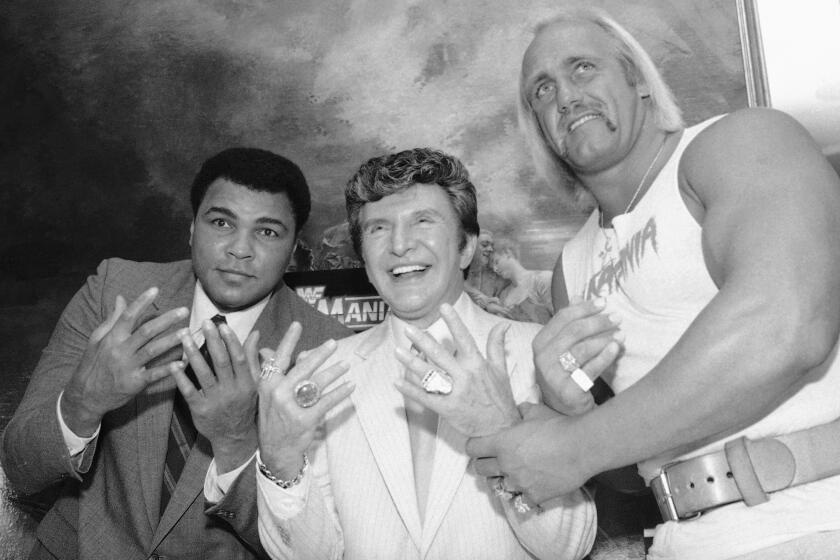

Salam Al-Marayati, the president of the L.A.-based Muslim Public Affairs Council, said not since Hakeem Olajuwon has a Muslim athlete been capable of such unifying impact.

“The sports arena is where the Muslim athlete is completely integrated into society as the rest of us struggle to become integrated,” he said. “I remember [former Laker] Jamaal Wilkes came to our mosque here back when he was playing, telling us the best way to overcome discrimination is success — in business, sports, whatever you do. Our job is to become part of American society, and Amir Khan represents that.”

Sports marketing expert David Carter of USC’s Marshall School of Business has looked at Khan’s career too.

“He is a long way from the big time, but if he has a clear positioning statement — this is why I’m here — and if he wins, he has a chance to exact change, even if it starts in small and incremental ways,” Carter said.

“There are signs of hope. He’s a young kid who might be a little naïve, but who can fault him for wanting to send a positive image? That resonates at any age.”

twitter.com/latimespugmire

More to Read

Get our high school sports newsletter

Prep Rally is devoted to the SoCal high school sports experience, bringing you scores, stories and a behind-the-scenes look at what makes prep sports so popular.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.