Boxer Abner Mares seeks to make a difference in ring and in inner city

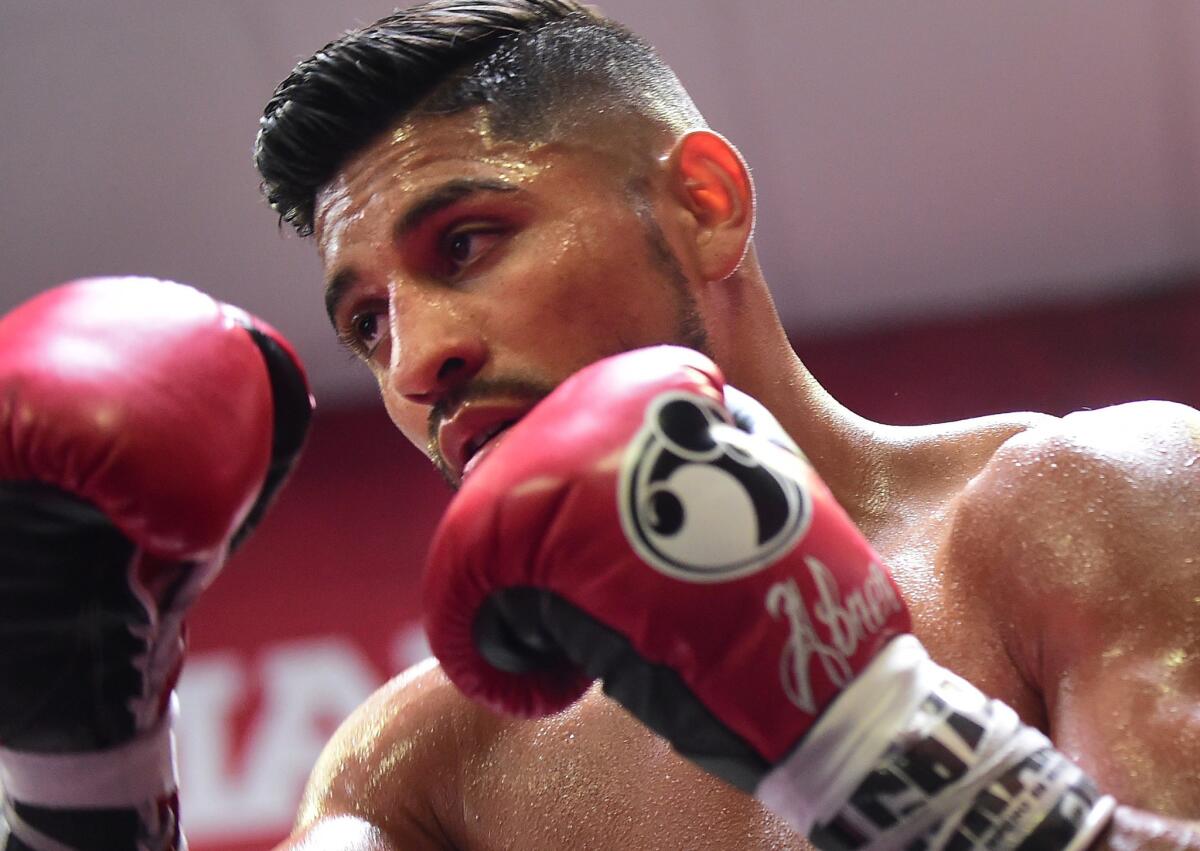

Boxer Abner Mares works out for the media on Aug. 18 in Bell Gardens ahead of his “Battle of Los Angeles” match against Leo Santa Cruz.

Ten years ago this summer, the sounds of police helicopter blades roared above Hawaiian Gardens. Armed men trampled the asphalt, shouting on the barricaded street looking for a cop killer as residents took cover.

Abner Mares knew the gang member with devil horns tattooed on his forehead who’d pulled the trigger. “Sepy” lived across the street. Not knowing the manhunt was targeting Sepy, Mares stepped outside his home when he heard the commotion of law enforcement authorities’ search and watched.

At the time, Mares was just four professional fights into a boxing career that would take him to world titles in three weight divisions, but he also wasn’t so far removed from the menace of gang life.

For Mares, the violent episode marked the intervention that separated him from his past focus on street activities to his pursuit of success in the ring. On Saturday at Staples Center, the 29-year-old Mares (29-1-1, 15 knockouts) will participate in one of the biggest fights of the year, against the Southland’s unbeaten Leo Santa Cruz (30-0-1, 17 KOs), a two-division champion, in a featherweight bout on ESPN.

Mares was born in Guadalajara, Mexico, and grew up in Southern California. But when he was in his early teens his parents learned their boy was being initiated toward gang membership, so they sent him back to stay near family in Mexico.

“I had punched a cop once, got beat up by one,” Mares recalled. “We thought the police were the bad guys. We’re taught to think that way growing up in the ‘hood. … You’re young. You think you own the world, think you’re indestructible.”

Jose Luis “Sepy” Orozco wasn’t indestructible. He now resides on death row for the first-degree murder of Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Deputy Jerry Ortiz, a gang enforcement officer who was investigating Orozco on suspicion of attempted murder but was instead surprised by the career criminal and shot point-blank in the face.

Mares later learned that Ortiz was a boxer too, an amateur who in his free time fought Marines and Los Angeles Police Department officers in charity competition.

To honor Ortiz’s service and community activism, two Southland youth centers that provided boxing training as an alternative to street life were named in his honor, one in El Monte operated by his family and another in South Los Angeles staffed by sheriff’s personnel.

Earlier this year, Mares was scrolling on Instagram when he saw that what was formerly named the Jerry Ortiz Boxing Club in Florence was seeking donations to stay open.

“Being aware of what happened to Deputy Ortiz, being as fortunate as I am now, and knowing those kids are in the same kind of place where I came from, I knew boxing could help them,” Mares said. “I knew I wanted to help out.”

So Mares, even if he’s relocated to a more comfortable life in Downey, has made a push to try to make a difference in the inner city. He has spoken to the estimated 200 young members of the newly named Century Sheriff Gym, invited a group of elite fighters from the group to a private workout, distributed 500 back-to-school backpacks to children who reside near the center and bought 100 tickets for neighborhood kids to his fight Saturday.

“If you train hard, even if you’re in a tough neighborhood, you can make it,” said Omar Campos, 18, one of the center’s fighters. “It’s pretty hard where we live, but I love what I do and that [center is] like my home.”

Sheriff’s Deputy Carlos De La Torre, 35, who along with a fellow deputy helps mentor those at the center, said, “A person at Abner’s level can create the inner-city rapport we so desperately need. To gain trust, being in the community is important. Abner has expressed how important it is to succeed in so many parts of life. Not just boxing. Go to school, be a great human being.”

Mares recounted, “I remember our school [anti-drug] program DARE and I can’t even tell you what it meant. I used to just laugh, not have a care about it, because we went back to our world and were fed something completely different.”

The scope of crime in his former neighborhood was revealed in 2011 when prosecutors closed the federal gang sweep launched by the Ortiz shooting.

Operation Knockout ended with a 30-year prison sentence for George Manuel “Boxer” Flores, who admitted in a plea deal to distributing from local homes mass quantities of drugs, including heroin, crack cocaine, methamphetamine and marijuana, while overseeing the Varrio Hawaiian Gardens gang. More than 100 guns were seized and 57 people were charged with crimes during Operation Knockout.

Mares understands fully that this type of gang activity remains in the Southland.

“Yes, but now these kids have an example right here. … I’m an example of making something from my life and I came from where they’re coming, right here in L.A.,” Mares said, raising his voice so others in the gym could listen. “When people tell you you can’t do things, they’re wrong.”

What helped turn Mares around was a string of victories and scholarship money he began earning in Mexico in amateur boxing tournaments that took him to the 2004 Olympics in Athens.

“You start evolving, and see you’re not the person you thought you were, that it’s a tough world out there,” Mares said. “Seeing results from boxing, I realized, ‘There’s something. … Maybe I can make something of this.’”

One of those young boxers at the gym was Gerardo Garcia, 15, who said Mares has taught him that “If he can do it, I can do it. If there’s a way I can, I will.”

Twitter: @latimespugmire

More to Read

Get our high school sports newsletter

Prep Rally is devoted to the SoCal high school sports experience, bringing you scores, stories and a behind-the-scenes look at what makes prep sports so popular.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.