Boxing documentary on head injuries delivers an important message that hurts

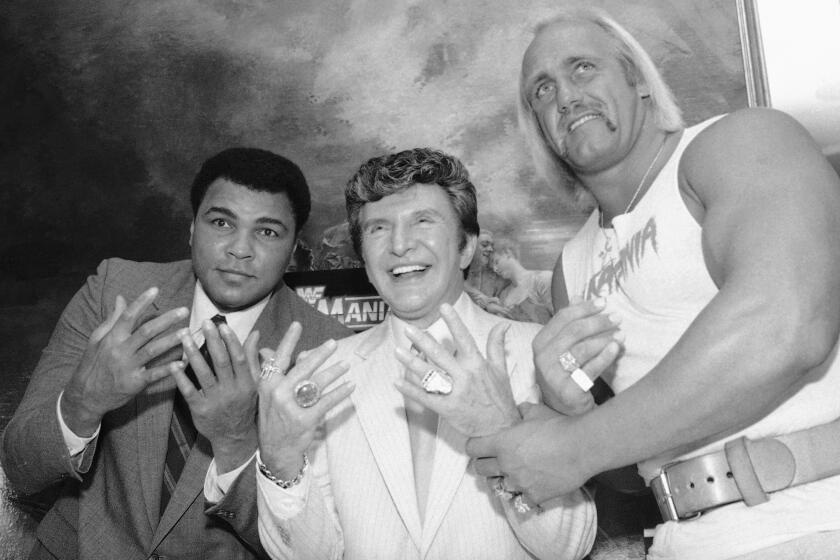

The tall, handsome man entered the room slowly, but with head held high. He was once heavyweight boxing champion of the world. Now, he moved along behind a walker.

Could it have been 1973, 37 years ago, that Ken Norton had broken Muhammad Ali’s jaw and won his title? Could this be the same once-great athlete who had forced the state of Illinois to change its high school track and field entry rules because he had won all eight events he tried?

The others swarmed to greet him. Men with limps, flat noses and faces of scar tissue rushed to pose for pictures with him, fists clenched in the traditional boxing poses. Alex “The Bronx Bomber” Ramos was there. So was Danny “Little Red” Lopez, Ray “Boom Boom” Mancini, a handful more. All had been world-class boxers, had known fame, fortune and the bright lights above the canvas.

It was to be a night of reunion, and it was. Also, a night of harsh reality.

The occasion was the screening of a little-known, little-publicized documentary titled “After the Last Round.” Its theme is head injuries in boxing. Perhaps 25% of the audience had one, and maybe half of those were willing to admit it.

The executive producer is Santa Barbara filmmaker Tom Moyer, whose best success has been the TV show “Critter Gitters.” It was directed by Ryan Pettey, with production help from Moyer’s son, Pat.

“I made the movie because I was so tormented,” said Tom Moyer.

His father, Tom Sr., had been a national AAU champion. He is 92 now. His uncle, Harry Moyer, had also been an amateur boxing champion. He is 96. Harry had two sons, Denny and Phil. They lived in Oregon and got into boxing as amateurs. For a while, their uncle, Tom, trained them.

Eventually, they turned pro and Denny became a star, even beating Sugar Ray Robinson once. If you are old enough to remember the “Gillette Cavalcade of Sports” and its Friday night fights, you remember Denny Moyer. He was a staple, as was Phil.

Tom Moyer idolized his cousins. He spent long days doing odd jobs around the gym as they trained.

Then he watched them grow old, deteriorate and lose their ability to do even the most simple tasks. These two larger-than-life characters of Tom Moyer’s childhood, his own flesh and blood, had become grown men in diapers, sitting in rocking chairs, as nurses cleaned the drool off their chins.

They were Oregon’s version of Southern California’s Quarry brothers, Jerry and Mike, now both gone as victims of pugilistic dementia. Denny succumbed July 1, at age 70. He had had 139 professional fights, 20 in his last two years. Phil, a few years older, is alone now in the convalescent home.

One searing image from the film is Phil, sitting alone on his bed, wearing his ever-present football helmet minus the face guard, face mostly blank. Above his bed is a poster of Muhammad Ali.

Another is of Harry, when both his boys were still alive, wiping their noses and pushing them, one by one, down a hallway in a cart.

“I didn’t want them to turn pro,” Harry says, his face showing the pain of a man who started his two sons on a path to brain death and needs to be able to believe he isn’t totally responsible, which he isn’t.

He holds a boxing glove from Denny’s induction into the Hall of Fame, and says, “I really don’t think this was worth it.”

The film isn’t all about the Moyers. It was just inspired by them.

There is Ali, slurring his rationalizations about why he is healthy enough to keep fighting.

There is a disabled Tony Bruno, a former boxer from Denver in his 50s now, meeting Jeff Rehman, who had unknowingly inflicted near-fatal brain damage to his close friend Bruno 30 years ago in a college sparring session. Bruno says, “I don’t think I remember you.” A distraught Rehman says, “I’m so very sorry.”

There is the wife of current heavyweight DaVarryl Williamson, watching him get knocked out and saying later, “My biggest fear is taking that plane ride home alone.”

After the screening, there was a panel discussion that was as jarring as the film. From it came the ridiculous, yet understandable, rationalization of men who knew that what they had done for a living was ill-advised and dangerous.

Ramos said that he had frontal lobe damage, but had no problems. Then he rambled enough to raise questions.

Tony “The Tiger” Lopez said he was aware he was forgetting things but said, “I really don’t care, because if I cared, I’d remember.”

Mancini told the audience about his 1982 fight with South Korean Duk-Koo Kim that cost Kim his life. “I didn’t kill him,” Mancini said. “He passed away because of a result of a fight.”

Norton didn’t speak. He didn’t have to.

“After the Last Round” is among those documentaries still in the nomination pool for an Academy Award. It has had minimal distribution, which is a shame.

So is its subject matter.

More to Read

Get our high school sports newsletter

Prep Rally is devoted to the SoCal high school sports experience, bringing you scores, stories and a behind-the-scenes look at what makes prep sports so popular.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.