25 years ago: Pete Maravich’s tragic trip to Pasadena

Pete Maravich came to town 25 years ago, Jan. 5, 1988. No newspaper, local or national, had an obituary prepared. No need, presumably.

Everything seemed normal that morning in the gymnasium at the First Church of the Nazarene in Pasadena. Maravich had flown in from his Louisiana home to do some radio work with James Dobson. Maravich had become a born-again Christian. Dobson was the nationally known head of Focus on the Family, his spacious headquarters located at the intersection of the 57 and 10 freeways in Pomona.

Dobson, 6 feet 5, was then 51, loved sports, was once captain of the tennis team at Pasadena City College and put together morning pickup basketball games at Nazarene on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays. This was a Tuesday, but it was a special day.

FOR THE RECORD:

Pete Maravich: A column in the Jan. 5 Sports section about the death of basketball legend Pete Maravich during a trip to Pasadena 25 years earlier said that James Dobson of Focus on the Family, whom Maravich was visiting, had been on the tennis team at Pasadena City College. Dobson attended Pasadena College, which relocated to San Diego and is now known as Point Loma Nazarene University. —

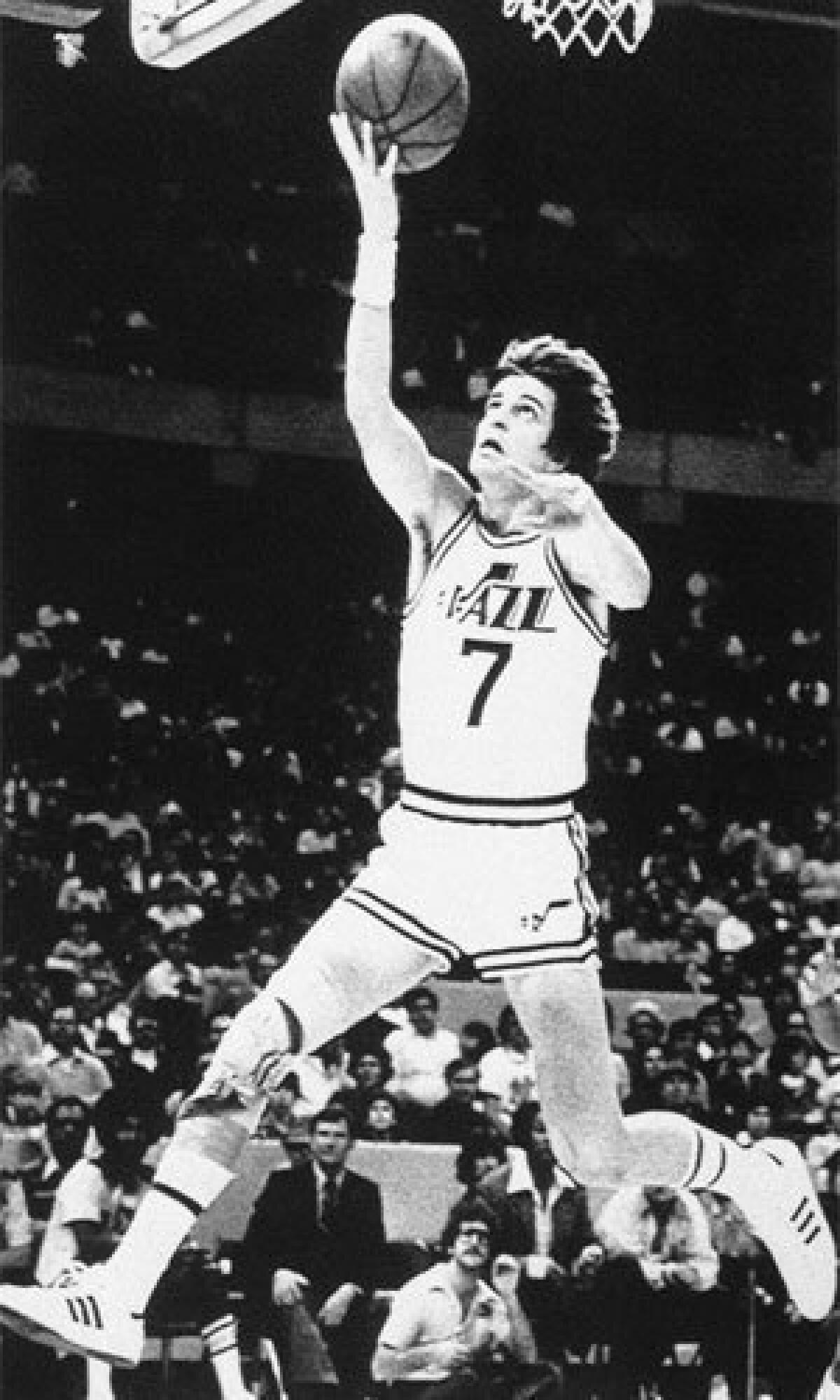

The guy with the scraggly hair and floppy socks was joining the game. Maravich was 40 then, but only eight years removed from his last season in the NBA, when he made 67% of his three-point shots in limited playing time with the Utah Jazz and Boston Celtics. That 1979-80 season was the first for the three-point shot in the NBA. Had it been around earlier, his legacy in the pro game might have grown considerably. As it was, he averaged 24.2 points in his 10-year career.

There was no question about his collegiate legacy. As the heart of Louisiana State’s 1967-70 machine-gun offense, directed by his dad, Press Maravich, Pistol Pete took an average of 38 shots a game and finished his career with a DiMaggio-like standard of 44.2 points a game. Like Joe DiMaggio’s 56-game hitting streak, Maravich’s 44.2 won’t be topped.

For a while, he turned football-crazed LSU into a basketball school. He was a one-man show, a white Globetrotter. Press put a basketball in Pete’s hands at age 5. The boy dribbled it a few times and never stopped. Not in movies, while he sat and watched. Occasionally, not even as a passenger in a slow-moving car. He’d open the window and bounce away, dribbling off the pavement. He could spin the ball on his fingertip and dribble between his legs and behind his back as routinely as he could walk. His shooting range was anywhere inside the gymnasium.

A recent article by Yahoo.com’s Jeff Eisenberg quoted former Georgia guard Herb White on the challenge of guarding Maravich, especially with the myriad screens set by LSU teammates.

“It was like trying to catch a housefly in a really dark room full of refrigerators,” White said.

Another former Georgia guard, Bobby Lynch, has a large picture of himself going against Maravich, with a caption that says he held Maravich to 69 points that night.

Maravich had games so spectacular that opposing fans carried him off on their shoulders. In one game, his team ahead, Maravich dribbled out the clock so adeptly that nobody could catch and foul him. Then, in the closing seconds, he added the exclamation point by tossing in a 35-foot hook shot for his 57th and 58th points of the game.

Interestingly, on that fateful day in Pasadena, one of the people in the game was among those unimpressed by the razzle and dazzle.

“I guess I was a UCLA snob,” says Ralph Drollinger. “That wasn’t the way we played, not what John Wooden taught. We thought it was unimaginable to play like that.”

Drollinger, a 7-foot-2 center from La Mesa near San Diego who played on Wooden’s national championship teams in 1973 and ’75 and was the first collegiate player to make it to the Final Four all four years, got a call from Dobson the day before the pickup game in Pasadena. They had worked together on various Christian media productions, but Drollinger says his value that day was completely athletic.

“Jim said Maravich was coming to town and he needed me,” Drollinger says. “He wanted to win.”

Drollinger, who postponed a pro career to play for Athletes in Action, a Christian evangelical team, and now heads the Members Bible Study that ministers to members of Congress in Washington, left his home in Lake Arrowhead that day at 4 a.m. to make it to the Pasadena gym for the 6:30 pickup game.

“Pete was the same,” says Drollinger, who was 34 at the time. “Droopy socks, floppy hair. I always said you couldn’t guard him by watching his hair. It always went the opposite way of his body.”

They played three-on-three for about 20 minutes and took a break. Drollinger walked to a drinking fountain and then Maravich — standing near Dobson, and just after proclaiming “I feel great” — collapsed. There were a few seconds, Drollinger says, “when we all thought he was faking, just joking.”

You can’t fake foaming at the mouth, and soon, Dobson and Drollinger were doing CPR.

Drollinger understood the procedure because he had been in dangerous situations before. He is a world-class mountaineer, has been as high as 18,000 feet, and is credited as the first man to climb every peak on the main ridge of the Sierra Nevada between Olancha and the Sonora Pass.

“We worked on him for what seemed like an hour,” Drollinger says, “but it was probably 15 minutes. I think he was dead the minute he hit the ground.”

Drollinger, Dobson and others waited about two hours at Pasadena’s St. Luke’s Hospital for the inevitable news. The shocking detail was that Maravich, who had run tirelessly on basketball courts for 30 years of his life, had done so while missing a left coronary artery in his heart. His right coronary artery had become greatly enlarged and had given out.

The headlines the next day were appropriately big and dark. It was a stunning story, with national impact and huge regional ramifications. For a time in the South, the biggest names and biggest shows were Maravich and Elvis.

Now, they both had left the building.

More to Read

Get our high school sports newsletter

Prep Rally is devoted to the SoCal high school sports experience, bringing you scores, stories and a behind-the-scenes look at what makes prep sports so popular.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.