Snubbing some all-time greats

Jerry Kramer used to be bitter about being snubbed by the Hall of Fame, the former Green Bay Packers guard who was an integral part of five championship teams in the 1960s vowing to stick it to the pro football shrine in Canton, Ohio, if he had the chance.

“I decided early on that if they ever called, I was going to send them a statuette of my fist with a middle finger raised and tell them to put that in the Hall of Fame,” Kramer, 78, said by phone from his home in Boise, Idaho. “I was angry.”

Then the years turned to decades, the resentment faded, and Kramer decided he would not let the snub define him.

“You look at what the game has given you, what a wonderful ride it’s been, with an incredible coach and teammates, and life-changing experiences,” said Kramer, who played for Vince Lombardi. “And you’re going to allow one award to cast a negative light on that? Heck no, that’s stupid.”

But as healthy as acceptance seems, it can be confusing at times. Like when NFL Commissioner Roger Goodell called four summers ago and, after discussing the league’s pension plan, asked Kramer whether he was going to Canton for the upcoming induction ceremony.

“No, Mr. Commissioner, I’m not,” Kramer said, recalling the conversation.

“How come?” Goodell said.

“Because I’m not in the Hall of Fame,” Kramer said.

“You’re not?” Goodell said. “What the heck is that about?”

Or the next summer when former New England Patriot John Hannah, a fellow lineman who was enshrined in 1991, called Kramer to ask whether he was going to the ceremony.

“I don’t think so,” Kramer said.

“How come?”

“Because I’m not in the Hall of Fame.”

“Huh?”

And so on.

“I got introduced as a Hall of Famer for a long time, and I’d always straighten them out — ‘I’m in the Packers Hall of Fame, not the big one,’ ” Kramer said. “But that got so awkward and uncomfortable, I just stopped correcting people.

“The thing that’s puzzling to me is they keep giving me awards and honors and applause and recognition. It’s like a guy who has 99 presents under the tree and is ticked off because he didn’t get the one he wanted.”

Kramer is hardly alone on the cusp of sports immortality. There are more than 1,000 athletes enshrined in the baseball, football, basketball and hockey halls of fame, and for every one there are at least a dozen relegated to the Hall of Very Good.

There are also a handful of baseball players who would be Hall of Fame locks if not for their suspected performance-enhancing drug use (Barry Bonds, Roger Clemens, et al) or lifetime bans for gambling on the game (Pete Rose), but they don’t belong in this group.

Here’s a look at the best of the rest, three players from each sport who belong in the Hall of Fame but aren’t:

BASEBALL

Jack Morris

The ultra-competitive and dependable right-hander, who amassed 254 victories, 2,478 strikeouts and was a three-time 20-game winner, fell short in his 15th and final year on the writers’ ballot, garnering 61.5% of the vote, but many consider his credentials, save for a career 3.90 earned-run average, Cooperstown worthy.

Morris, who pitched 18 years from 1977 to 1994, started three All-Star games and three World Series openers. He was 4-0 in the 1991 postseason and threw what many consider the second-greatest World Series game in history behind Don Larsen’s perfect game, a 10-inning, Game 7 shutout of Atlanta in 1991.

Tim Raines

Craig Biggio, who led off in more than half of his 2,850 games, is a virtual Hall of Fame lock — he fell two votes short of selection this year — but Raines was a better leadoff man, with a .294 average, .385 on-base percentage, 1,571 runs, 170 home runs, 980 runs batted in and 808 stolen bases in 23 years (1979-2002).

Biggio had a .281 average, .363 OBP, 1,844 runs, 291 home runs, 1,175 RBIs and 414 stolen bases in 20 years. Raines, overshadowed during his career by the great Rickey Henderson, had an 84.7% success rate, best among players with at least 300 stolen bases, but his early-career cocaine use appears to be hurting his candidacy.

Tommy John

The left-hander, best known for the revolutionary elbow surgery now named after him, had a 26-year career that rivals that of Bert Blyleven, who is in the Hall. John was 288-231 with a 3.34 ERA, 2,245 strikeouts, 1,259 walks, 302 home runs given up, 162 complete games, 46 shutouts and a 1.283 WHIP (walks and hits per inning).

Blyleven was 287-250 with a 3.31 ERA, 3,701 strikeouts, 1,322 walks, 430 home runs given up, 242 complete games, 60 shutouts and a 1.198 WHIP in 22 years. Blyleven had better pure stuff but gave up far more home runs. Each finished among the top four in Cy Young Award voting three times.

FOOTBALL

Tim Brown

The explosive receiver and return man played 16 of his 17 NFL seasons with the Raiders, racking up 1,094 receptions for 14,934 yards and 105 touchdowns from 1988 to 2004. At the time of his retirement, he ranked second all-time in receiving yards and third in receptions and touchdown catches (100).

Beginning in 1993, Brown had nine consecutive 1,000-yard seasons and 10 consecutive years with 75 catches or more. His best season came in 1997, when he caught 104 passes for 1,408 yards and set a team record with seven 100-yard games. Brown was selected to the Pro Bowl nine times.

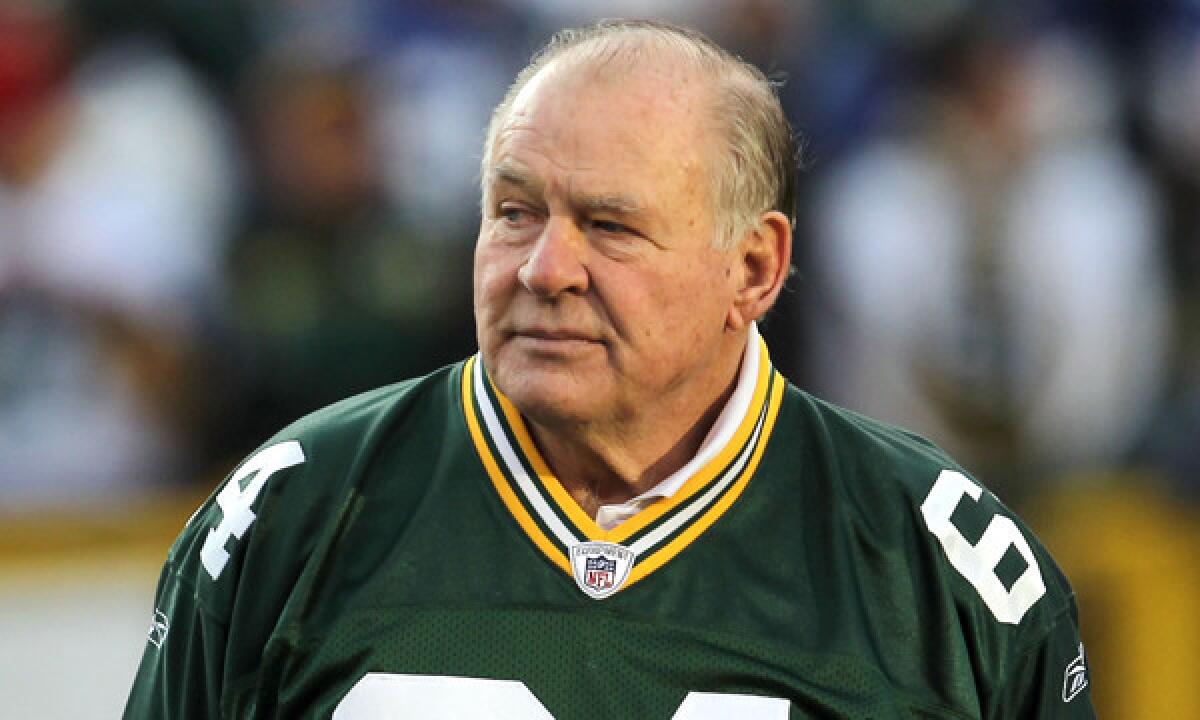

Jerry Kramer

“Behind the block of Jerry Kramer … “

So begins the call of NFL Films narrator John Facenda (a.k.a. “The Voice of God”) on Bart Starr’s one-yard touchdown plunge with 13 seconds left that gave the Packers a 21-17 victory over the Dallas Cowboys in the 1967 NFL championship game, known as the “Ice Bowl.”

Kramer was a five-time All-Pro who played 11 seasons despite 22 surgeries. He was the Packers’ kicker for three seasons. He is the only member of the NFL’s 50th Anniversary team, picked in 1969, that is not in the Hall of Fame.

Ray Guy

The knock against Guy, like the one against longtime designated hitters in baseball, is that he was a specialist, but there has been no better NFL punter than Guy, for whom the term “hang time” seems to have been invented.

Guy, whose powerful, high and accurate kicks often changed the complexion of games, was a seven-time Pro Bowl player in 14 seasons (1973-86) with the Raiders and was selected to the NFL’s 75th Anniversary team. He’s in his 23rd year of Hall eligibility.

BASKETBALL

Kevin Johnson

Now the mayor of Sacramento, Johnson averaged 17.9 points and 9.1 assists per game in 13 seasons (1987-2000) and led Phoenix to 10 consecutive playoff berths. He made the All-NBA team five times and finished in the top 10 of most-valuable-player voting twice.

Johnson ranks 18th on the NBA’s assist list (6,711) and is sixth in assists per game. As inclusive as basketball’s Hall of Fame is, with 340 inductees, far more than the other three sports, there should be room for one of the game’s best point guards.

Mitch Richmond

Had his career not overlapped Michael Jordan’s, Richmond may have been the best shooting guard of the 1990s. He averaged 21.0 points, 3.9 rebounds and 3.5 assists from 1988 to 2002, played in six All-Star games and was All-NBA five times.

Richmond has the highest number of career points (20,497) of any eligible player who has not been elected to the Hall of Fame, but is probably hurt by the fact that he played in only 23 playoff games.

Sidney Moncrief

Moncrief, who played the point and the wing, was one of the best all-around guards of the 1980s, averaging 15.6 points, 4.7 rebounds and 3.6 assists in 11 seasons, shooting 50% from the field and 83% from the free-throw line.

The five-time All-NBA selection finished among the top eight in MVP voting for five straight seasons (1981-86). He also won two defensive-player-of-the-year awards and was selected to the all-defensive team five times.

HOCKEY

Jeremy Roenick

The charismatic center scored 513 goals and had 703 assists for 1,216 points and ended his 20-year career (1988-2009) with the third-highest goal-scoring total of U.S.-born players, behind Mike Modano and Keith Tkachuk.

Roenick, a nine-time All-Star, was a forward who played with an edge, racking up 1,463 penalty minutes. He had two 50-goal seasons in the early 1990s with Chicago. He had 53 goals and 122 points in 154 playoff games.

Dave Andreychuk

The winger is probably a victim of longevity, amassing his 640 goals in 23 seasons from 1982 to 2006. But he ranks 14th on the NHL’s all-time scoring list and first in power-play goals with 274, more than Wayne Gretzky and Gordie Howe.

Known as much for his persistence and professionalism, Andreychuk refused a trade to a contender in 2001-02, remained in Tampa Bay and went on to help the Lightning win the Stanley Cup title in 2004.

Eric Lindros

Lindros is the anti-Andreychuk, his injury-shortened 13-season career (1992-2007) deemed too short by many for Hall entry, but the gifted center was a physically dominating skater who had 372 goals and 865 points in only 760 games.

Blessed with a rare combination of size (6 feet 4, 240 pounds) and skill, Lindros ranks 19th in NHL history with 1,138 points per game. He excelled in the playoffs, scoring 24 goals and 57 points in 53 games, and was the NHL MVP in 1994-95.

Twitter: @MikeDiGiovanna

More to Read

Get our high school sports newsletter

Prep Rally is devoted to the SoCal high school sports experience, bringing you scores, stories and a behind-the-scenes look at what makes prep sports so popular.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.